Russian soprano Anna Netrebko as Elvira in Bellini's I Puritani at the Met Opera (2007)

Russian soprano Anna Netrebko as Elvira in Bellini's I Puritani at the Met Opera (2007)

What is the current state of opera in the music and theater world? Where has it been and where will it go to attract newer and younger audiences, as well as keep up their interest? I've asked these questions before, and about opera's continuing relevancy for our time. Today and in subsequent posts, we will explore some of the options.

After a year and a half of the coronavirus pandemic and after singers, directors, production personnel, chorus members, musicians, designers, and the like have insulated themselves in semi-seclusion, the opera world, like the 17-year cicada, is itching to bust out from self-imposed hibernation.

Yes, out of the deep, dark gloom and into the ... where, pray tell? Hopefully, not the breach! Though opera's demise has been foretold on more than one occasion, there is still hope for its redemption.

The Old and the NewsThe belated announcement of the Met's having reached an accord with its staff and crew was most welcome indeed. The follow through, however, hasn't been so pleasant: the Met asked those same folks for a 30 percent pay cut. Can you imagine? With prices soaring on a variety of goods and services (to include - but not limited to - gas, water, rent, electric, and other essentials), the priming of the economic pump doesn't sound so tempting for us mortals.

As you can see, there are always compromises to be hammered out: some good, some not so good.

But it's nice to know that we can still drown our sorrows out, but not our hopes, in beautiful sounds. And that's what this latest essay is about: a brief rundown of Met Opera productions "On Demand" that we've missed reporting on and that have come to light by way of constant probing. Our never-ending quest for enlightenment, for something unique to watch and listen to, has elicited some unusual and quite extraordinary candidates for cogitation.

There once was a time when that trusty standby, the New York City Opera, led the way in providing avant-garde entertainment for consumer consumption. Readers may remember that two of Argentine composer Alberto Ginastera's more dissonant forays, the operas Don Rodrigo and Bomarzo, premiered at NYCO in the 1960s and '70s, with Don Rodrigo (1966) having introduced unsuspecting audiences to a strapping, up-and-coming lad named Plácido Domingo.

Other surprises boasted a new production of Handel's Giulio Cesare (with Beverly Sills as the sultry Cleopatra, and Norman Treigle as Caesar), Douglas Moore's The Ballad of Baby Doe (also with Sills), Carlisle Floyd's Susannah (with Treigle's superb Olin Blitch), Boito's Mefistofele (Treigle again, in the title role), and many others. NYCO had also placed itself at the forefront of the bel canto revival in restoring Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor to its proper place in the repertoire, presenting the opera complete for once; and in championing the same composer's cause with the long-dormant Tudor trilogy of Anna Bolena, Maria Stuarda, and Roberto Devereux (all starring Ms. Sills).

They weren't the only ones. Coming a tad late to the party, the Met hopped onboard the bel canto express in the 1970s with a new production of Vincenzo Bellini's final opera, I Puritani. Was it too little, too late?

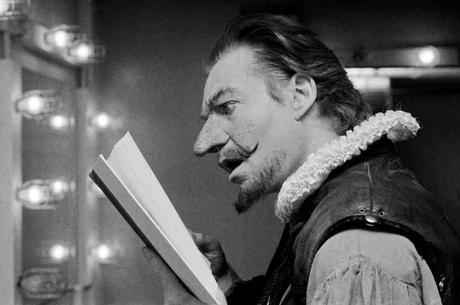

I Puritani (2007). This Sandro Sequi production from the bicentennial year 1976, with sets by Ming Cho Lee, certainly made up for lost time (well, sort of). The Met Opera reintroduced I Puritani di Scozia (its full title) into its now-expanding repertoire with a strong cast headed by Joan Sutherland, Luciano Pavarotti, Sherrill Milnes, and James Morris. The conductor was Richard Bonynge, Sutherland's husband. Not the subtlest of participants, but a most reliable group, nonetheless. With this effort, the Met did its best to welcome bel canto back into the fold, where Bellini's opus had not been heard from in many a generation.

In this 2007 Live in HD revival, Russian soprano Anna Netrebko took on the part of Elvira (there goes that name again!), with lightweight tenor Eric Cutler given the nearly impossible task of singing Arturo (effortful high Cs and Ds, thank you), along with Italian baritone Franco Vassallo as Riccardo and Canadian bass-baritone John Relyea as Elvira's uncle Giorgio. Patrick Summers took over the reins as conductor.

Musically and dramatically, there's a multiplicity of coincidences in both Bellini's opera and Donizetti's output, specifically with his Lucia di Lammermoor. No one dies, thank goodness, in Puritani, but there's a requisite Mad Scene for soprano in both works, as Elvira, in the Bellini opus, goes in-and-out of sanity, at times comically so. There's also a baritone who's smitten with the heroine and a rival beau to match (much as in Verdi's Ernani), in addition to a pair of fatherly figures, one of whom, Giorgio, acts more like her surrogate papa. The minor role of Queen Henrietta (sung by mezzo Maria Zifchak), who plays a key element in the preposterous plot, figures prominently only in Act I.

So where's the relevance? What's missing is that essential connection one has to characters and their plight. I'm afraid that here, and in much (but not all) of Bellini's output, the point remains the singing.

Vassallo had the right equipment, but missed the bel canto grace this assignment cries out for. Relyea's imposing height and fullness of voice were right for his part. And to be fair, Vassallo and Relyea gave a rousing rendition of their Act II duet, "Suoni la tromba" (literally, "Sound the trumpets"), even if they made it sound more like Verdi. Cutler, on the other hand, struggled with the tessitura of Act III. Maestro Summers put the singers through their paces and kept a steady hand on the proceedings. Still, there was little he could do to enliven the proceedings, the staging and sets being from another generation's aesthetic entirely.

Surely the raison d'être for this revival was the presence of Ms. Netrebko. She was the audience's favorite, hands down, with her every utterance greeted by howls of approval. And without supremely talented colleagues, there is little impetus for playing this piece. The same goes for the tenor. Once such major advocates as Juan Diego Flórez, Lawrence Brownlee, and Javier Camarena arrived on the scene, things took a decisive turn for the better. For the most part, the dreary staging mitigated whatever was going on vocally. Glory and honor are the main points of this piece; factor in a huge suspension of disbelief to accompany Elvira's on-again, off-again mental state and you have an operatic cliché in the making.

One problem is that many productions of this and other Bellini works fail to take into account the delicacy with which the Sicilian-born composer, who died much too young in life, imbued his subjects. Most interpreters mistake him for his contemporary Donizetti, or the livelier bombast of Verdi. Nothing of the kind! Bellini's music, like that of his contemporary Chopin, is of a delicate filigree; one that served as an integral link between the classical bel canto world of the early 1800s, with its impressive line and embellished strictures, and the rising tide of nationalistic vigor encompassed by late Rossini and early Verdi. Romanticism, in Bellini's hands, remained subtle and vibrant.

As for Donizetti, the poor wretch ended up a syphilitic wreck, dying a miserable death in an insane asylum. Bellini, too, passed away much too soon of that least theatrical of illnesses: dysentery and/or gastric enteritis. With Rossini filing for early retirement, that left one man standing: Verdi. We need not tell you how his career turned out.

Meanwhile, Back at the Plaza...Other pioneering efforts at City Opera showcased such rarities as Korngold's Die tote Stadt ( The Dead City) with Carol Neblett and John Alexander, Montemezzi's L'Amore dei Tre Re ("The Love of Three Kings") with bass Samuel Ramey, and new takes on established classics, i.e., Frank Corsaro's revelatory staging of Gounod's Faust and Verdi's La Traviata (both of which I saw), with Treigle, then Ramey as the Devil, and Patricia Brooks and Dominic Cossa as Violetta and the elder Germont, respectively.

Fine, but what about the magnificent Met? Where has that venerable house been while these NYCO productions were upstaging their neighbor across the Plaza? To be honest, the stodgy old Met lagged behind her sister company in many respects, due mostly to its mission of, in the first place, preserving, protecting, and defending the core repertory; and secondly, in catering to deep-pocketed subscribers, many of whom had sustained the company through thick and thin. We know, too, that in times of financial distress those same subscribers lean more toward a "conservative" bent than to so-called vanguard elements. Understandable.

But the time to play it safe was over. Over the years, glimpses of innovation have emerged, both in the recent past and in future presentations. Some of these can be glimpsed through Met Opera on Demand, the company's streaming service via the Roku app. Infrequently seen oddities such as Zandonai's Francesca da Rimini, Berlioz's Les Troyens, and Cilèa's Adriana Lecouvreur have proven their worth and been formerly reviewed by yours truly. Seeing them again, with different casts, can provide one with distinctly new and fresher perspectives, along with continuing regard (or not) for the results.

For instance, hearing Renata Scotto's squally Francesca from 1984, alongside the outpourings of the dashing Domingo as Paolo, made one realize how much better their acting was this time around, as opposed to Dutch soprano Eva-Maria Westbroek's inauthentic 2013 take on the part. In that same 2013 revival, Mark Delavan's pugnacious Gianciotto and Marcello Giordani's lover-boy Paolo could actually have passed for battling brothers, whereas Domingo and the mammoth-toned Cornell MacNeil bore no familial resemblance whatsoever. Straining credibility, then, can complicate matters when viewed from too close a perspective - one of the pitfalls of opera in high definition.

In the Berlioz work, tenor Bryan Hymel's ringing tone and brilliant top notes as Aeneas (2012) clearly outclassed Domingo's more modest resources (from 1984). Still, both artists did their best with what they had to work with: in Domingo's case, a horribly ill-fitting costume stood beside ugly sets and décor. What helped was that his co-stars included two of the classiest singers this side of midtown: mezzo Tatiana Troyanos as Queen Dido, and Earth Mother Jessye Norman as the prophetess Cassandra. Wow! That combination beats Mr. Hymel's partners, Susan Graham as Dido and Deborah Voigt as Cassandra, by a Gallic nose, but not by much.

As I've mentioned before, there's a lot of good and not-so-good in every work. How about the bad? I wouldn't mention that term. My belief is that there is no "bad" as such in opera. To quote Master Yoda's paraphrase of Shakespeare, "Do or do not. There is no try." And try they must, even if the results fail to pan out.

At best, opera is the most arduous, the most taxing, truly the most demanding art form there is. Don't forget, these artists are emoting at top volume. Take it from me, high and low notes can be effortful in the extreme, especially in a large theater. The work required to do justice to a part, to concentrate on the score, to remember your lines, to convey the text in intelligible fashion, and to know your place in the general scheme of things, while hurling the voice at full tilt into a massive auditorium - all of these take strength, concentration, stamina, and musicianship.

Opera tests a performer like no other form of entertainment. And it's all done live, folks, and in your face. Or, in the case of online streaming, recorded and preserved live, as it occurs.

Was It Real or Was It Verismo?So what gives with the staid repertoire, anyway? When will matters improve along that front? Will audiences ever get to experience such rarities as Leoncavallo's Zazá, a work that once enjoyed currency at the old Met on Broadway and 39 th Street? How about Mascagni's Lodoletta, Guglielmo Ratcliff, or his charming L'Amico Fritz? What of Wolf-Ferrari's Il Segreto di Susanna and I Quattro Rusteghi? And how meaningful are these works for us today? I'm all for a production of Clièa's L'Arlesiana, which deserves a fair shake. There are so many worthwhile items to explore from the verismo period alone that room should be given them on the Met's production calendar.

Take, for instance, Leone's opera L'Oracolo, a favorite of the great baritone Titta Ruffo. Certainly a revival or two can be called upon, can't it? That is, if the money and circumstances prove favorable. Wishful thinking on my part? Perhaps. But, hey, what does the company have to lose, except new subscribers?

As a matter of fact, one of those old gems, Alfano's rarely heard Cyrano de Bergerac, was bought to the Met stage in 2005. It starred Roberto Alagna as the titular long-nosed hero (Domingo took up his sword for the 2017 revival). Was the opera an unqualified success? Did it stir the bones in like fashion? Not quite, wrong move. I heard the work on the radio and caught glimpses of it on YouTube. To be perfectly honest, this oddity did not merit the effort that was put into it. There's little that was memorable. In fact, I held my own nose in order to get through it. Sorry people!

Not since the Royal Shakespeare Company's Broadway tour of 1984 has justice been done to French playwright Edmond Rostand's poetic farce. The version I happened to catch (faithfully translated by Anthony Burgess) was headed by the estimable Derek Jacobi and Sinead Cusack. I'll never forget the balcony scene where Mr. Jacobi as Cyrano, the spotlight focused on his illumined face and protruding proboscis, spoke the name of the woman he loved, "Roxane, Roxane," over and over again in softly-whispered reverence. You could sense the entire Gershwin theater holding its collective breath as the actor luxuriated in the moment, a romantic respite between swashbuckling flights of fancy. Call it stage magic or what have you, no opera could hope to capture the profoundness of that sequence.

As for Alfano, his claim to fame was that he was the sole composer willing and able enough to have tackled Puccini's unfinished score for Turandot. Not even the fiery conductor of the premiere, Arturo Toscanini, was pleased with the results. So what did he do? Well, Toscanini cut and re-scored Alfano's ending to his satisfaction. I managed to hear the original Alfano orchestration when (you guessed it) the NYCO restaged the Beni Montresor production in the mid-1980's.

So, what did I think of the refurbished Turandot? Let's say that it was ... uh, different, otherworldly, not quite what one expected, but full-bodied and entertaining (I really dug the extra high notes for tenor). Was I bowled over by it? Not really. I expressed a similar dissatisfaction for Luciano Berio's tacked-on rewrite, first staged in 2002 at the Vienna State Opera, under Valery Gergiev's direction. This highly bowdlerized edition was neither Puccini nor Alfano, nor was it very Italianate-sounding. It was patented Berio, whatever that means. Some experiments are just not worth the effort. They hold only modest interest for audiences of today.

So, can another chestnut from the golden age of verismo provide the requisite thrills?

Fedora (1997). Known as Umberto Giordano's follow-up to his popular Andrea Chénier, the relatively short three-act Fedora, based on another of those Sardou specialty items for actress Sarah Bernhardt (his La Tosca became the source for Puccini's eponymously titled opera), finally hit the Met stage in a lavish 1997 production by Beppe De Tomasi, with sets by Ferruccio Villagrossi, and costumes by Pier Luigi Cavallotti. The opera was conducted by Roberto Abbado.

With the likes of veteran soprano Mirella Freni as the titular Russian princess (vocally past her prime, but nicely interpolated), tenor Plácido Domingo as Loris (high-powered and committed), and baritone Dwayne Croft as de Sirieux (suavely sung) in the cast, you would think this old warhorse from the turn of the last century would have paid the dividends in terms of potency and staying power. Not quite. To compare it to the earlier Chénier (which premiered in the same year as Puccini's La Bohème) does Fedora a disservice. The unusual settings - the story opens in Russia in contemporary times, which then switches to a swanky Parisian soirée and a Swiss mountainside villa for the two outer acts - are about as far from recognizable verismo as one can imagine.

True, red-hot passion, of the kind found in Cavalleria Rusticana and Pagliacci, the two most familiar models from the verismo repertoire, is certainly not lacking in Fedora. What's missing is a believable story line: full of violence and obsessions (oh, gobs of it!), the plot blends sentiment and melodrama with murder, espionage, and secret trysts. For all the personal entanglements, real flesh-and-blood characters and credible responses are absent; the drama remains earthbound, the ending about as abrupt and tacked on as a power outage, though not so sudden as in La Rondine (see below).

Mainly, the action moves by way of letters, memos, and furtive notes, all of them delivered by timely post or last-minute messenger. You got to hand it to the postal service, though: They always deliver the bad news first. Whatever happened to efficient mail service, anyway?

Despite all this, the main aspect is that this piece, and numerous others that came before and after it, took up the prevailing trend of adapting existing literary works (i.e., period pieces and novels, along with newspaper accounts, personal journals, diaries, exposés, and such) by transforming them into operatic conveyances. One striking moment in Act II of Fedora introduces a concert pianist (real-life artist Jean-Yves Thibaudet) in the non-speaking role of Boleslao Lazinski, who plays a lovely nocturne in the manner of Chopin.

An opera in the grand tradition (scaled down for modern ears), Fedora will strike listeners as bearing a "passing" likeness to Puccini's later La Rondine, especially in that work's opening sequence which also features a pianistic platform for the tenor playing the poet Prunier. The soprano's death by inhaling a poison is plainly reminiscent of Adriana's passing in Cilèa's opera, Adriana Lecouvreur.

This is another of those "pseudo-dramatic touches" that mark this and other related works for what they are. With its soaring vocal lines (the famously brief tenor arioso, "Amor ti vieta"), scorching obsessions, exotic locales, the presence of Russian spies, and a tragic suicide at the end - all of these taking place in either a Czarist St. Petersburg or a distinctly Russophile-flavored Gay Paree - Fedora has been better served on discs rather than in the opera house, an ironic fact of theater life.

End of Part Five

(To be continued....)

Copyright © 2021 by Josmar F. Lopes