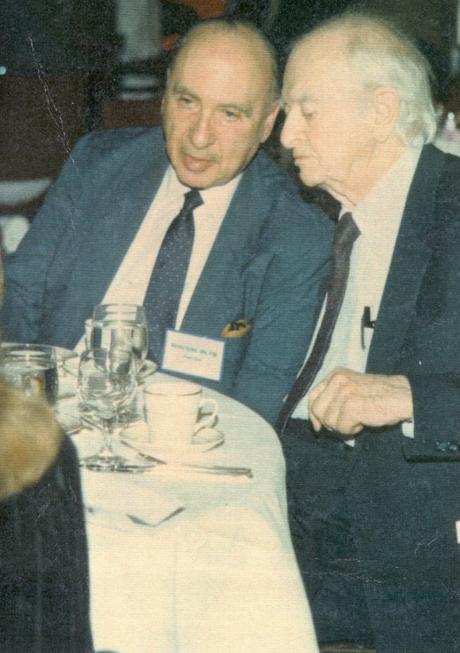

Abram Hoffer and Linus Pauling at the symposium, “Adjuvant Nutrition in Cancer Treatment,” Tulsa, Oklahoma, November 1992.

Abram Hoffer and Linus Pauling at the symposium, “Adjuvant Nutrition in Cancer Treatment,” Tulsa, Oklahoma, November 1992.[Part 1 of 10]

“If there is evidence, for example, that an increased intake of ascorbic acid decreases the amount of illness with the common cold and other diseases, and the evidence is in fact strong, it is not improper to recommend that parents give vitamin C to their children, to see if it leads to an improvement in their health. In the same way orthomolecular (megavitamin) treatment of schizophrenia, in addition to the conventional methods of treatment, is justified by the facts that a good number of psychiatrists have reported it to be of value and there is little danger in serious side effects from the vitamins.”

-Linus Pauling for the Journal of Autism and Childhood Schizophrenia, November 1974

Orthomolecular Medicine, loosely defined as the pursuit of optimal health through the intake of the “right molecules” in the “right amounts,” is the discipline that defined Linus Pauling’s work for the last three decades of his life. The undertaking marked a dramatic shift away from the research that Pauling had pursued previously; work that garnered him a reputation as one of the leading scientists of the twentieth century. The shift was made all the more dramatic by the level of commitment that Pauling made to pursuing this new area of study: not only did he write multiple books on the topic, he also co-founded an institute to explore new ideas on orthomolecular medicine.

Today, the bulk of Pauling’s research output on orthomolecular topics centers on the use of vitamin C to treat the common cold and cancer. Less known is the fact that Pauling’s initial foray into orthomolecular topics focused on the treatment of schizophrenia.

One might propose that Pauling first became interested in orthomolecular treatments for mental disorders as the result of happenstance and boredom. In 1965 Pauling visited a psychiatrist friend in Carmel, California for a party. When his interest in socializing began to wane, Pauling wandered the house and picked up a book that seemed interesting, Niacin Therapy in Psychiatry, by the Canadian scientist, Abram Hoffer. As Pauling would soon learn, the book focused on treating schizophrenia with vitamins, specifically niacin. This idea was new to Pauling and provoked considerable interest.

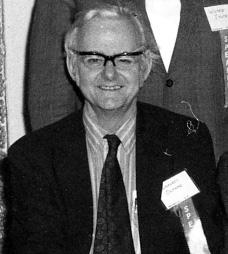

Humphry Osmond, 1972

Humphry Osmond, 1972In his book, Hoffer detailed the experimental work that he and a colleague, Humphry Osmond, had conducted to demonstrate the positive impact that high levels of niacin – one of the B vitamins – made on the mental functioning of patients with schizophrenia. In these trials, Hoffer and Osmond had treated their patients with megadoses of niacin and other vitamins that were routinely more than a thousand times higher than the recommended daily allowance. The duo reported that, through years of megadosing, their patients never experienced negative side effects and often found relief from their illness. In effect, Osmond and Hoffer had seemed to find an effective treatment for schizophrenia that bore few to no side-effects. This accidental book that Pauling picked up would help start him down a path to studying the orthomolecular treatment of mental illness.

Even though Pauling had found Hoffer and Osmond’s book interesting, he did not initially understood how his own scientific background could be applied towards orthomolecular approaches. But a bit of further reflection on work that he had done decades earlier helped to clarify the connection and prompt a new round of investigations.

In the 1940s, Pauling had tried to see if he could diagnose phenylketonuria (PKU) through a simple urine test. PKU is a birth defect that diminishes one’s ability to properly break down amino acids. If left untreated, the resulting build-up of amino acids can lead to mental disabilities, seizures, and even death. Pauling thought that it might be possible to diagnose PKU patients by conducting laboratory analyses of enzymes that were naturally excreted through urine. Though this specific project ultimately proved unsuccessful, Pauling believed that his failures were not due to problems with the theory, but instead could be sourced to inferior technologies of the era that were not sensitive enough to make a proper analysis. Years later, when reading about Hoffer and Osmond, Pauling realized that he could apply urinalysis to their work.

For PKU patients suffering from an enzyme imbalance, health could be restored by ingesting doses of supplemental enzymes. Pauling extended this model to Osmond and Hoffer’s results, suggesting that niacin succeeded in reducing patients’ symptoms precisely because schizophrenics were suffering from an imbalance of enzymes; megadosing was a means of restoring balance in their brains.

In a 1967 paper, Pauling made it public that he had been working and ruminating on the concept of megadosing. He used the same publication to define this specific type of orthomolecular therapy as, “the treatment of mental disease by the provision of the optimum molecular environment for the mind, especially the optimum concentration of substances normally present in the human body.” He would go on to posit that “The functioning of the brain and nervous tissue is more sensitively dependent on the rate of chemical reactions than the functioning of other organs and tissues.” As such, “I believe that mental disease is for the most part caused by abnormal reaction rates, as determined by genetic constitution and diet, and by abnormal molecular concentrations of essential substances.”

Pauling’s realization that his past urinalysis work could connect with orthomolecular therapy was just one reason why he became involved in the research. Pauling was also driven by a fundamental belief that the human need for certain vitamins, such as vitamin C, was an evolutionary phenomenon. According to Pauling,

the process of evolution does not necessarily result in the normal provision of optimum molecular concentrations. Let us use ascorbic acid [vitamin C] as an example. Of the mammals that have been studied in this respect, the only species that have lost the power to synthesize ascorbic acid and that accordingly require it in the diet [in addition to humans] are many other primates (rhesus monkey, Formosan long-tail monkey, and ring-tail or brown capuchin monkey), the guinea pig, and an Indian fruit-eating bat.

By extension, this evolutionary precedent might also imply that, even though certain enzymes are essential, they are still not readily produced in the quantities that we need. Pauling postulated from there that mental imbalances, sometimes manifesting in illnesses such as schizophrenia, could be a result of inherited enzyme imbalances.

Pauling also knew that deficiency diseases such as scurvy (which results from a deficiency in vitamin C) and pellagra (which results from a deficiency in niacin) can both manifest as mental illnesses. People with scurvy often suffer from mood changes and depression, and people with pellagra are sometimes beset by hallucinations or dementia. This correlation between mental illness and nutritional deficiency was echoed by Abram Hoffer, who wrote that, “if niacin was removed entirely from food, everyone would become psychotic in one year.”

Eventually, numerous other maladies would fall under Pauling’s definition of an orthomolecular disease. Diabetes, for instance, was the result of an insulin imbalance and its treatment entailed the injection of insulin, therefore it was an orthomolecular disease. Goiters too were seen as an orthomolecular disease because they occur as a result of iodine imbalance and were treated with iodine dosing. Even cavities could be viewed through an orthomolecular lens, given their prevention with supplemental fluoride. Possibilities of this sort fascinated Pauling and would consume much of his time in the years to come.