Ava Helen and Linus Pauling at the White House with President Gerald Ford and other recipients of the National Medal of Science, September 18, 1975

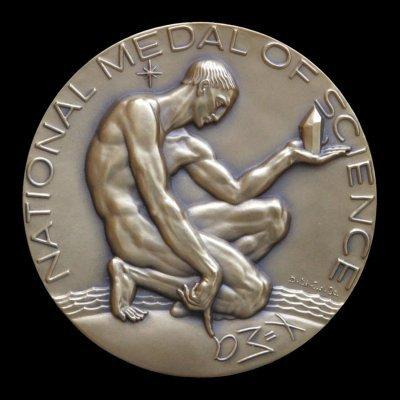

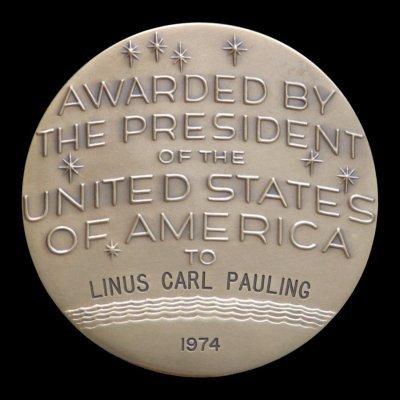

On September 18, 1975, the determination of many sectors of the scientific community culminated in an early afternoon ceremony held in President Gerald Ford’s Oval Office. It was on this date that Linus Pauling at long last received the 1974 National Medal of Science, an award that was long in the coming.

Immediately after the news of his selection was announced, Pauling began to receive a steady stream of congratulatory letters from friends and colleagues. In many of these communications, Pauling’s scientific peers made reference to the long delay that had preceded Pauling’s receipt of the award. One suggested that “in my estimation you should have been the very first chemist to receive this recognition” and another opined that “this is an honor which, for you, is long past due.”

Permeating much of this dialog was a common understanding as to the cause of the delay: namely that Pauling’s outspokenness on social and political issues had not been appreciated by high ranking officials of the U.S. government. As one correspondent put it

we know that you would have long ago received this honor if you had been silent during the Vietnam War and if you had not spoken out on every occasion in the interest of the people of the United States as a peace-loving nation.

Tagged as a communist in the 1950s and scorned by many for the consistency of his anti-war point of view, Pauling was used to fighting for the recognition that he deserved, and the case of the National Medal of Science proved to be no exception.

Established in 1959, the National Medal of Science is the most prestigious honor bestowed upon scientists by the U.S. government. Pauling, who had made significant contributions to a staggering array of scientific disciplines by the late 1950s, was clearly a leading candidate for the medal from the moment of its inception. However, his vocal campaign against the perils of the nuclear age served to politicize the process by which he might have been considered for the award, the result being that others were chosen in his stead for fifteen years.

In the run-up to 1974, a growing controversy had built around Pauling’s lack of recognition by the White House. Though scientists on the President’s Committee for the National Science Award had persistently put forth Pauling’s name as a preferred choice, he was continually passed over. The controversy heightened once word began to circulate that President Richard Nixon had pointedly refused to grant Pauling the award not once, but twice.

Some two decades later, Pauling learned that Nixon had been so upset by the tenacity of the American Chemical Society and the American Crystallography Association – organizations that both refused to put forth any nominations other than Pauling – that he decided to forego conferring the award at all. And indeed, no scientists received the decoration in 1971 or 1972.

While certainly a slight against him personally and to the scientific community writ large, Nixon’s refusal to honor Pauling with the medal may have actually come as something of a relief. It is safe to say that Pauling’s relationship with Nixon was fraught with tension and mutual distaste to the point where a meeting between the two would have proven awkward. As Pauling would later point out in a reply to a congratulatory letter, “I am at least glad that it was delayed beyond the Nixon regime.”

The slights weren’t all coming from the nation’s capital. Closer to home, Pauling found himself in a tussle with a local paper, the Palo Alto Times, that had neglected to mention Pauling as being included in the membership of the class of 1974. Instead, in an edited United Press International story headlined “Stanford prof awarded national medal,” the paper focused on the achievements of Paul Flory, a recent Nobel laureate who was soon to retire from the Stanford faculty. A final paragraph listing all of the 1974 recipients did not include any reference to Pauling nor, to be fair, three other scientists who were to be likewise honored.

When he contacted the paper to complain and suggested that the publication’s omission had been “damaging” to him, Pauling was met with a rebuke: “The city editor said I was a great scientist but a lousy lawyer, and they would print the story how they wanted to.”

A similar situation played out with the San Francisco Chronicle, which ran a different story emphasizing two Bay Area scientists in the class – Flory and Ken Pitzer – but not Pauling. A subsequent follow-up with UPI confirmed to Pauling that his name had been included in the wire release issued by the news service to its regional offices.

Many others shared a far more positive view of Pauling’s decoration. For some, President Ford’s decision to award Pauling with the National Medal of Science signified a welcome thawing of relations between scientists and the executive branch. As one newspaper editorial noted, “the withheld honors for the great scientist had come to symbolize a growing estrangement between the government and the scientific community.” In addressing this estrangement symbolically, Ford seemed to be indicating that a scientist could speak their mind without fear of penalty.

In remarks published in The Medical Tribune, James Neel – a fellow member of the 1974 award class – held up Pauling as a role model and suggested that the government’s recognition should serve as validation for all socially motivated scientists. In Neel’s estimation

[Pauling] personifies the best in the psyche of the scientist: he is interested in the way life functions and in keeping living things alive. His social views are thus an extension of his work and values as a scientist. His greater perception of the meaning of life is what gives significance to his ideas and resonance to his contributions.

Others, however, understood that Pauling’s road to the National Medal of Science had been rocky and offered private words of support. As biochemist Britton Chance, also a member of the class of 1974, noted

you may have had mixed feelings as to whether [the National Medal of Science] was worthy of your accomplishments….[but] you have had a really remarkable career, and as I hope you know, to my view you are truly the out-standing genius of our time.

By the time of his passing in 1994, Linus Pauling had received forty-seven honorary doctorates as well as essentially every award that a scientist in his fields of study could win. And though the theatrics surrounding his belated National Medal of Science award surely proved frustrating, one might posit that the commendation of peers like Britton Chance served as stronger validation for Pauling than did nearly all of the hundreds of medals, plaques and certificates that he received over the course of a hugely distinguished career.

Advertisements &b; &b;