Lunch and Learn

Sharpless reading Pinkerton’s letter to Cio-Cio-San, from Act II of Madama Butterfly

Sharpless reading Pinkerton’s letter to Cio-Cio-San, from Act II of Madama Butterfly

I mentioned in my previous post, regarding Puccini and North Carolina Opera’s presentation of Madama Butterfly, that I attended a seminar in late October on the background of the work in question, vis-à-vis its Western representations of Japanese culture.

The seminar, held at the Research Triangle Park Institute, covered such wide-ranging topics as the singing and staging of the opera through the ages, presented by North Carolina Opera’s General Director, Eric Mitchko; “One Fine Day (or not): Some Problems in the Music of Madama Butterfly,” with the lively Tim Carter, Professor of Music at UNC-Chapel Hill; “Three Divas of Japan,” discussed by Jan Bardsley, Professor of Asian Studies at UNC-Chapel Hill; and “Pinning the Butterfly: Western Accounts of Madame Butterfly,” given by Inger S.B. Brodey, Associate Professor of English and Comparative Literature, also from UNC-Chapel Hill.

For the naturally curious opera buff among us (myself obviously included), or anyone else interested in how the story of Madama Butterfly came to light and was transformed from a one-act American play into a full-fledged Italian operatic vehicle, the seminar provided plenty of opportunity for reflection, discussion and thought on the creative process.

Among the more fascinating aspects were Eric Mitchko’s comparisons of key scenes from the opera, using familiar recordings from more-or-less the time of the opera’s premiere and after, and from live performances not commercially available elsewhere.

The live rendition of Cio-Cio-San’s spotting of Pinkerton’s ship as it pulls into port was performed by Renata Tebaldi, then at the very top of her form. She gave an emotionally overwhelming interpretation of the scene, full of her trademark portamenti and rubati, as well as sure-fire vocalism. A rare video clip of Butterfly’s farewell to her son preserved one of the few live performances of the part by the legendary Leontyne Price near the end of her career. She, too, pulled out all the stops in what can only be described as an unbelievable outpouring of Price’s signature top notes and endless legato phrasing. As they say in showbiz, the crowd went wild in both excerpts, and justifiably so.

In other sections, Tim Carter’s erudite dissection of Cio-Cio-San’s Act II solo, “Un bel di” (“One fine day”), and its relationship to classical oratory (i.e., the librettists’ use of Cicero’s rhetorical devices), in addition to his bubbly discourse on the opera’s music (contrasted with excerpts from Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Mikado) and its sources in Japanese and Chinese folk melodies, were masterful in their depth and perception, as well as filled with the professor’s learned commentary and gushing enthusiasm for the subject.

Along similar lines, Jan Bardsley’s enlightening talk comparing “Three Divas of Japan” — specifically, the writer and Zen practitioner Hiratsuka Raicho, Japanese soprano Miura Tamaki who made a career out of performing Cio-Cio-San, and the actress Matsui Sumako — to such American practitioners as actress Blanche Bates and opera diva and Hollywood star Geraldine Farrar, proved fascinating in its glimpses of the phenomenon of traversing cross-cultural boundaries; and the effect that upper-class New Women of early twentieth-century Japan had on such traditional elements of Japanese society as “visiting a Tokyo teahouse to be entertained by a geisha.”

Inger Brodey’s equally absorbing analysis, “Pinning the Butterfly: Western Accounts of Madame Butterfly,” in which she provided an in-depth look into the origin of the Butterfly story through real-life personages, along with marvelous period photographs (which also comprised the bulk of Professor Bardsley’s segment), segued directly into the concluding panel discussion and question-and-answer section on the topic “Engagement and Appropriation: Art, Aesthetics and the Other.”

On the whole, this was a most rewarding and pleasurable afternoon spent in pursuit of the elusive Butterfly. It not only helped with my own research regarding the composer’s music and life, but led to a better understanding of and appreciation for what went into the preparation behind one of my all-time favorite works.

Music to My Ears

Talking about Puccini, his sure hand as a musical dramatist and orchestrator comes through loud and clear with Madama Butterfly, which stands as a paradigm of his mastery of dialogue, atmosphere, characterization and motivation.

Whether one describes the opera as part of the verismo movement (i.e., “realism”) or as an exemplar of naturalism, which formed the crux of Belasco’s own theatrical ambitions (one, by the way, that had a major influence on the burgeoning silent cinema), there’s little doubt that Butterfly has held its own in the opera house. Littered about the score are literally hundreds of illustrations of Puccini’s use of leading motifs — recurring themes and melodies and snippets of tunes that jar the memory in ways that call to mind the innovations of Richard Wagner.

This is not to say that Puccini was the perfect Wagnerite — far from it! But that he learned from, and ultimately adhered to, many of the German master’s precepts (Manon Lescaut served this purpose quite nicely) is incontrovertible. What made Puccini stand out from his compatriots — particularly fellow Lucchese Alfredo Catalani, who died of tuberculosis six months after Manon Lescaut’s 1893 premiere and whose surviving work (Loreley, La Wally) paid a profound tribute to German romanticism — was the manner in which he seamlessly wove his characters’ dialog and music into the threads of the plot.

Puccini had a way of drawing the listener into his protagonists’ world with a specificity of purpose and economy of means unmatched by his fellow countrymen. The varied exchanges between Pinkerton and Sharpless all through Madama Butterfly, while reminding audiences of Rodolfo and Marcello’s equally recurrent ones in La Bohème, nevertheless are differentiated by the composer’s shaping of the vocal line to the needs of the libretto.

To cite only a few examples, how similar-sounding is the theme of Rodolfo’s “O Mimì, tu piu non torni,” from the start of La Bohème’s Act IV, to Pinkerton’s third-act arioso, “Addio, fiorito asil,” near the end of Madama Butterfly. Both start off low and end up high, with the baritone in each instance elucidating his point of view at defined intervals. The difference between them lies in their mood: the first one carries with it an air of nostalgia and longing for the past — a loss, if you will, of past loves, but with the hopeful expectation of moving on; the second is filled with regret and remorse, of having committed an irreversible wrong with no hope of turning back, the end result being shame and despair.

The opening dialog between Pinkerton and Goro follows this same pattern, with short phrases and relevant banter, punctuated by lively interjections that are always lyrically based and distinctly “in character.” Natural interruptions to the flow, such as the famous one present in Pinkerton’s vigorous narrative “Dovunque al mondo,” where he poses the question to Sharpless as to whether he’d like to be served “Milk punch or whisky?” are typical of normal, everyday conversation among friends — an extraordinary realization of opera’s aim of turning discourse into song.

No other opera composer to my knowledge, with the exception of the Russian Modest Mussorgsky in Boris Godunov and Khovanshchina, the Czech Leoš Janáček in Jenůfa and The Makropoulos Case, or the Italian Verdi in his final masterwork Falstaff, has so faithfully rendered “real-life” situations in music as Puccini has done here. He continued expanding his art to the next level with La Fanciulla del West (itself based on another Belasco play), and with Il Trittico (“The Triptych”), especially the one-act opus Gianni Schicchi, a paean to maestro Verdi.

Puccini returned once more to the orient with his final opera, the incomplete and grandly opulent Turandot, where much of the give-and-take between tenor and baritone can be heard in the wonderfully harmonious Trio of the Masks between the ministers Ping, Pang and Pong in the first scene of Act II.

Overlooked Source

In reading about and researching where and when the story of Madama Butterfly came into being and how its librettists, Illica and Giacosa, helped shape the opera into its present form, one of the overlooked sources I happened to stumble upon was a French work from two decades prior.

No longer as frequently performed as it used to be (a shame, given its many treasurable tunes), composer Léo Delibes’ wrote a charming opéra-comique by the name of Lakmé (1883), which musicologists have strongly indicated as a prime influence on the plot of the Puccini piece.

Delibes’ librettists, Edmond Gondinet and Philippe Gille, adapted the story for their opera from the novel Le Mariage de Loti (published in 1880) by the mysterious Pierre Loti (real name: Louis Marie-Julien Viaud). Loti, who first expanded upon his adventures in Tahiti, went on to write a more widely-circulated tale, that of Madame Chrysanthème in 1887, which was a thinly veiled, semi-autobiographical account of his tour of duty as a naval officer in Japan, and his arranged marriage to a geisha in Nagasaki (sound familiar?). This, too, served as source material for Puccini and his team.

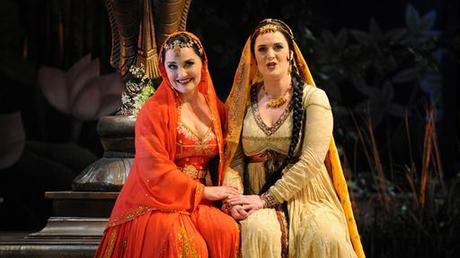

In any case, there are a multitude of resemblances between Lakmé and Butterfly, some astoundingly so. While Loti’s original story was set in the Pacific Islands, Gondinet and Gille placed their version in British-occupied India during the Raj. Lakmé (our stand-in for Cio-Cio-San) is the daughter of a high priest of Brahma, Nilakantha (or the equivalent of Cio-Cio-San’s uncle, the Bonze), who has a fanatical hatred of foreign rulers. Lakmé has a loyal maidservant, Mallika (her Suzuki), who together with her mistress partake of their own mellifluous and thrice familiar “Flower Duet,” to the languid rhythm of a barcarolle.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, Gérald (our caddish Pinkerton) is a British officer in Her Majesty’s Army who, being tall and quite handsome, falls in love at first sight with the exotically attractive Lakmé. This creates the inevitable clash of cultures which will bring down the title character in the end.

The tenor Gérald has a baritone companion, Frédéric (a makeshift Mr. Sharpless, if you insist), who tries to bring his lovesick pal back down to earth. There’s even a Kate Pinkerton-type by the name of Miss Ellen, who is Gérald’s neglected fiancée, and a comic foil in the person of Mistress Bentson (either the tipsy Uncle Yakuside, or any of Cio-Cio-San’s other relatives). And finally, one other character, the slave Hadji, sung by a comprimario tenor who spills the beans about Lakmé’s affair with the Englishman to her father, can be treated as a reasonable facsimile to Goro, the slimy marriage broker.

Needless to say, by the time Act III rolls around, the lovers have undergone various trials (including Gérald’s stabbing by the disguised high priest), which leads to Lakmé’s suicide by ingesting the leaves of a poisonous lotus flower known as the Datura stramonium. Despite being informed by his librettists that Datura stramonium was not exactly poisonous, Delibes ignored their counsel, thus sparking controversy among amateur and professional botanists for his deliberate disregard of science.

In the end, Lakmé dies a musical death, expiring in the arms of her lover — which was a “better” fate than Butterfly experienced with the return of her faithless husband, Pinkerton. As a melodious period piece with spoken dialog and colorfully alien Indian locale, Lakmé is best remembered for its faux orientalism and the gorgeous centerpiece, “The Bell Song,” which coloraturas from Lily Pons, Mado Robin, Gianna d’Angelo, Joan Sutherland, Mady Mesplé and Natalie Dessay have made famous.

Next to Puccini’s tragedy, however, Lakmé is a second-class citizen, albeit a close cousin operatically speaking, when compared to the grandeur attained by Cio-Cio-San’s tragic denouement.

(To be continued…)

Copyright © 2015 by Josmar F. Lopes