Flower Duet from Act II of NCO’s production of Madama Butterfly (Photo: Curtis Brown)

Flower Duet from Act II of NCO’s production of Madama Butterfly (Photo: Curtis Brown)I Remember It Well…

Okay, so it wasn’t the Metropolitan Opera’s critically acclaimed, Anthony Minghella-directed production from 2006. Get over it! That detail notwithstanding, North Carolina Opera’s more traditional approach to Giacomo Puccini’s tragic story of Madama Butterfly, presented on November 1, 2015 at the Memorial Auditorium in Raleigh, came as close as any to upstaging the Met in the singing, acting and conducting departments.

With a handpicked roster of talented young performers, to include soprano Talise Trevigne in the title role, tenor Michael Brandenburg as Pinkerton, mezzo-soprano Lindsey Ammann as Suzuki, bass-baritone Michael Sumuel as Sharpless, and tenor Ian McEuen as Goro, along with NCO’s Artistic and Music Director Timothy Myers at the helm, General Director Eric Mitchko can be proud of the fact that he had another qualified hit on his hands.

But before we get to the specifics, a little background history is in order. So let me say this at the outset: Puccini is my favorite opera composer, and Madama Butterfly is the work I heard most often as a youth. To that end, I can claim a more personal connection to the piece than most viewers, for on the night before I was born my parents went to see a performance of the opera at the Teatro Colombo in São Paulo, Brazil. Afterward, my father, who was a devoted opera fanatic, made the prophetic statement that his son would simply have to grow up loving the opera.

As luck would have it, dad’s pronouncement came true. Since then, I have seen numerous productions of opera as a whole, with Madama Butterfly at or near the top of the list. I have owned, and listened to, many of its most celebrated recordings, including the classic RCA Victor version with Toti dal Monte and Beniamino Gigli as the leads. I have read about and studied the opera through its libretto, books, articles and online websites. I even attended a recent seminar about its historical and cultural context, “Madama Butterfly: Japan and Its Western Representations,” presented by UNC-Chapel Hill’s Humanities and Human Values Program.

Accordingly, I consider myself a fairly knowledgeable fan of the opera’s riches. For me, then, Madama Butterfly epitomizes the essence of Puccini’s life and art. And anything and everything connected to the piece will lead me back to the conclusion that it is a singularly unique achievement within the composer’s body of works.

With that brief introduction out of the way, let’s get on with the show.

Madama Butterfly was Puccini’s sixth work for the stage, the first performance of which took place at the Teatro alla Scala, in Milan, on February 17, 1904. Considering how poorly the opera fared on that fateful night, it behooves us to explore some of the reasons for the debacle.

The Men Behind the Curtain

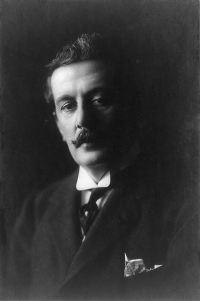

Giulio Ricordi remained unconvinced. Despite repeated assertions from its composer, Ricordi, the scion of one of Europe’s leading publishing houses, simply could not grasp what Puccini had in mind with respect to a one-act play about a fifteen-year-old Japanese geisha.

Signor Giulio, as Puccini respectfully referred to him, expressed delight in taking young neophytes under his wing — in particular, those few novices endowed with the gift for writing opera. He could boast of past accomplishments, among which was his outmaneuvering of Casa Lucca for the complete catalog of Wagner’s works. He had also received challenges from the upstart Sonzogno firm, whose own stable of composers featured the likes of Pietro Mascagni and Ruggero Leoncavallo, for dominance in the field.

As an experienced hand at music publishing, Ricordi had learned to deal with difficult personalities, the most inflexible of which was Verdi, the grumpy old “Bear of Busseto.” But handling a fellow such as Puccini, whose previous output included such revenue-generating items as Manon Lescaut, La Bohème and Tosca, tried his patience beyond the norm. Getting the easily distracted composer to concentrate on his work was a chore in itself. Not only that, but it took all of Ricordi’s renowned powers of persuasion to convince Puccini to decide on a subject and get down to the business of writing music.

For his part, Puccini no longer exuded the vigor of youth. By the turn of the century, he began to show signs of wear as he entered middle age. Puccini sensed his energies flagging, which Ricordi, in a later letter, callously attributed to sheer laziness or a bout with syphilis. Eventually, the cause of the composer’s malaise was diagnosed as a mild form of diabetes. But Ricordi’s rebuke left Puccini with mixed feelings about his father-son relationship to the older (and wiser) man.

Despite his concerns, Ricordi had enough faith in his meal ticket to assign his best team of librettists, the poets Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa — both of whom had worked extensively on all three of Puccini’s prior efforts — the unenviable task of turning American playwright David Belasco’s Madame Butterfly into a bona fide Italian opera.

Ever on the lookout for a good story, Puccini had the habit of falling readily in love with his female protagonists as they went through their own tribulations. The trick, as mentioned above, was to find a subject worthy of his affections. In his mind, there was little for Signor Giulio to be concerned about. Sooner or later, something would strike his fancy. Did Ricordi forget that he had three back-to-back “winners” in a row? Come to think of it, Manon Lescaut had proved a sensation in Turin, while La Bohème had taken considerably longer to find favor with the critics. The critics — hah! It was the public, he insisted, that would eventually learn to love Bohème. That’s all that mattered. On that point, Puccini was right.

Similarly, the overly melodramatic Tosca, with its murders and tortures and episode of attempted rape, had experienced a volatile first night in Rome (which an aborted bomb scare did nothing to help). Yet, it too became an established favorite. Prophetically, it was a new production of Tosca that brought the composer to London. While there, by chance Puccini had attended the showing of a one-act play at the Duke of York’s Theatre. It was on a July evening in the year 1900 that Madame Butterfly first came to his attention.

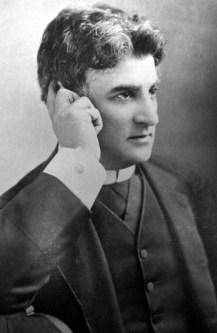

Although he spoke no English, Puccini was immediately taken with the strikingly attractive Evelyn Millard’s sensitive portrayal of Cho-Cho-San. But what most caught his discerning eye was a fourteen-minute interval — the night vigil, to be exact, one of those quintessential coups des théâtres that Belasco (nicknamed the “Bishop of Broadway” for his frock coat and clerical collar) was well-noted for.

As “dusk” began to settle over Nagasaki Bay, Puccini was held spellbound. The light show and bird calls that transformed the Duke of York’s stage into a replica of a Japanese postcard — and that Belasco personally supervised — had absolutely enthralled him. After months of fruitless searching, Puccini had found his next opera.

The Painful Road to Nagasaki

With Verdi’s passing on January 27, 1901, Puccini began to be hailed by fellow Italians as the late master’s heir apparent. This notion terrified the composer more than it reassured him. Basically, all he wanted out of life was to hunt and fish, to tinker with his motorcars and boats, to rendezvous with pretty ladies and, most notably of all, to compose at the piano — whenever the occasion moved him, of course. His rivals, however, had other ideas. They had set their sights on his next opus, whatever that might be. In our present-day parlance, they were “loaded for bear.”

As it happened, Puccini’s choice of a subject, i.e., the aforementioned Madama Butterfly — itself an adaptation by Belasco of lawyer John Luther Long’s short story — turned out not to be the grandiose operone that Ricordi had long insisted he compose. Not only that, but the principal character of Cio-Cio-San, the geisha who falls in love with an American naval officer, Lt. Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton, through a marriage of convenience, is abandoned by him. To make matters worse, when Pinkerton returns to Japan with “a real American wife,” his plan is to take Butterfly’s child away forever. This was not the type of romantic tenor lead that audiences would have expected at the time. No wonder Ricordi had doubts about the matter.

From the creative side of things, work on the opera progressed slowly. Right at the start, there were delays. For instance, it took an unusually lengthy time to obtain the rights — nine months in all, due mostly to miscommunication with Ricordi’s New York office. Finally, in early 1901, the way was cleared for Puccini to begin.

His plan was to turn the one-act play into a three-act drama. This was an unusual practice for him. With Manon Lescaut and Bohème, the source material had come from two French novels, from which various episodes were drawn to create his fast-moving operas. With Tosca, an exhaustively wordy five-act play by the Frenchman Sardou was vastly pared down and altered to arrive at a workable format for operatic purposes. Trimming the text to manageable proportions was part of Puccini’s methodology, what Master Verdi termed la parola scenica, or the “scenic word” — a concise summation of plot and thought in as few phrases as possible.

In the matter of Madama Butterfly, he and his librettists had no choice but to go beyond what was found in the one-act play: Act I would be based on aspects of Long’s story; Act II, the so-called “Consulate Act,” was an invention by Illica to contrast with the Japanese first act; while Act III would be all Belasco — ergo, the raison d’être for a work in three acts.

After spending an inordinate amount of time on the piece, Puccini experienced a sudden change of heart and insisted on a two-act treatment instead: an hour-long first act, to be followed by an even longer second act — an hour and a half, by his calculations, both set in and around Cio-Cio-San’s house. This midway course change met with disfavor from both Ricordi and his librettists, especially the intractable Giacosa, who threatened to walk out on the project altogether.

There were other complications as well, mainly the drawn-out love affair between the 40-something composer and the much younger Corinna — a law student or teacher, according to local reports — an affair that did not end happily for either party. In addition, Puccini’s own live-in mistress, Elvira Gemignani, was still legally married to her husband Narciso, a childhood acquaintance of Puccini’s. Puccini and Elvira even had a child out of wedlock, which added to their troubles. To this we add the problem of Narciso’s refusal to divorce Elvira on any grounds.

As the song goes, the “best” was yet to come: in February 1903, Puccini experienced a near-fatal car accident that left him with a fractured tibia and months of inactivity. The recovery period was slow and painful and complicated by his diabetes, with progress on the opera coming to a crawl. In the middle of these encumbrances, Corinna made it known that she wanted a more permanent relationship, which Puccini and his publisher feared might lead to adverse publicity.

The “good” news, if indeed there was any, had come the day after his car accident: Narciso, Elvira’s husband, had died suddenly from wounds sustained in a fight with another woman’s husband. It seemed that infidelity had reached epidemic proportions in the composer’s home district. You could even say that many of these occurrences would have made excellent material for an opera. Indeed, a case can be made that Puccini had written into his work more than a sufficient number of episodes from “real life,” which was the very root of verismo.

The above difficulties notwithstanding, within a year Puccini and Elvira were officially married (in accordance with Italian law and to untold pressure from Puccini’s sisters) in a furtive, late-night ceremony. Some time thereafter, Puccini negotiated a financial settlement with Corinna, who despite the money continued to squawk at how shabbily she’d been treated. (Years later, it was learned Corinna had been fleecing the impressionable composer out of his fortune, while continuing to engage in secret liaisons with other men — none of which sat well with anybody.)

Fiasco Made Easy

Puccini completed the opera on December 27, 1903, at precisely 11:05 pm. Pleased with the overall results, and with the two-act partition, as well as with the rehearsals (which had gone exceedingly well), Madama Butterfly was set to premiere at La Scala on February 17, 1904.

Ricordi’s son, Tito, was placed in charge of the production, with scenery designed by the Parisian-born stage-painter Lucien Jusseaume. A first-rate cast was assembled for the run: Rosina Storchio, Giovanni Zenatello and Giuseppe de Luca, all of them established artists. The conductor would be Cleofonte Campanini, the brother of tenor Italo Campanini.

Everyone’s spirits were up, including Puccini’s, who felt secure enough in the outcome to invite his entire family to the opening — the first time any of his relatives were present at one his operas. Due to the lingering effects of his car accident, Puccini necessitated the use of a cane. Because of this and his habitual shyness around the public, he had decided to sit backstage and away from the prying eyes.

In view of what subsequently took place, this was a wise choice. Posterity has recorded the opera’s first night as one of the grandest fiascos ever to have taken place at that venerable institution. As many had feared, rival factions and the presence of practical jokers in the auditorium, who “brayed like donkeys and mooed like cattle,” succeeded in wrecking Puccini’s delicate flower of a work, transforming his Butterfly into an unmitigated disaster.

The change to the opera’s structure, with no intermission between the two parts of the interminable second act, had proven to be a torturous test of the audience’s patience. Not that it made any difference, but the next day’s criticisms of the work were strictly on the negative side. Some reviewers praised the composer’s new musical direction, while others felt it was more of the same old, same old. Either Puccini had failed to anticipate the hostility hurled at his piece, or it was a mess from the start, neither of which would hold up over time. After the next day’s damage control session, Ricordi agreed to return his firm’s fee to La Scala. The work was withdrawn until further notice.

Three months later, on May 28, at a nearby theater in Brescia, Madama Butterfly was reintroduced with cuts to the first-act wedding scene, a revised entrance song for Cio-Cio-San (some in the audience had complained it sounded too much like Bohème), and a sensible intermission between the two parts of Act II. With the further insertion of the arioso, “Addio, fiorito asil,” for Pinkerton, as well as a trio for Pinkerton, Sharpless and Suzuki, a holdover from the discarded “Consulate Act,” the opera became the singular success its composer had initially predicted. Vindication at last!

After premieres in the major Italian theaters, along with new productions in London in July 1905 and New York in February 1907 — in particular the Opéra-Comique in Paris, also in 1907, where Puccini had sanctioned additional cuts to his score — the opera quickly found its way into the standard repertoire. Alongside La Bohème and Tosca, Madama Butterfly had joined their ranks as the composer’s three most frequently performed works.

(To be continued…)

Copyright © 2015 by Josmar F. Lopes