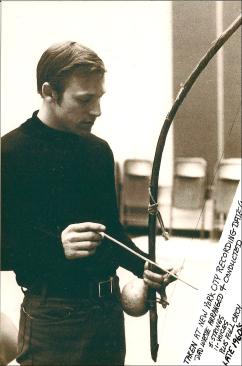

Me & Buddy Deppenschmidt at Strathmore, Education Room 309, June 8, 2014

Me & Buddy Deppenschmidt at Strathmore, Education Room 309, June 8, 2014The following is a transcript of an interview I conducted with jazz drummer Buddy Deppenschmidt, done at the Strathmore Music Center in North Bethesda, Maryland, on June 8, 2014, as part of the Jazz Samba Symposium dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the landmark Verve album, Jazz Samba.

William “Buddy” Deppenschmidt Jr. is an internationally respected performer, recording artist, and teacher who has been a member of the Newtown School of Music staff since the 1960s. Currently, Buddy teaches and is the artist in residence at the Community Conservatory of Music located in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. He studied with Dave Levin in Philadelphia, with classical percussionist Arthur Dextradeur, and with the legendary Joe Morello who was the long-time drumming sensation of the Dave Brubeck Quartet. Still active and going strong at 79, Buddy has toured the world and continues to lead an all-star band, Jazz Renaissance. His work appeared on three major motion picture soundtracks, six major record labels, and over 40 CDs. In addition, he has biographical listings in both Leonard Feather’s The Encyclopedia of Jazz in the Sixties and Barry Kernfeld’s New Grove Dictionary of Jazz.

Josmar Lopes – Now, to set the stage for what occurred in the 1960s, let me give you a little bit of background. Between the years 1958 and 1962, several incidents took place that would bring the country, people, and music of Brazil into sharper focus. It started off with Brazil beating Sweden, 5-2, at the World Cup. That was June 29, 1958. That occurred with the aid of a 17-year-old sensation named Pelé. A few weeks later, João Gilberto, a shy and reclusive – some would say obsessive-compulsive – singer/guitarist from Bahia recorded a 78-rpm single for Odeon Records. You remember the name of the song, Buddy?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – “Chega de Saudade.”

Josmar Lopes – “Chega de Saudade” (“No More Blues”) by the hit songwriting team of Antonio Carlos Jobim and Vinicius de Moraes. A year later, on June 12, 1959, Black Orpheus, a film shot on location in Rio during Carnival time, was released in France. This film, with music by Jobim, Vinicius, and Luiz Bonfá, another well known Brazilian musician, was an international sensation. It went on to win the Palme d’Or at the Cannes film festival, the 1960 Academy Award for Best Foreign Film, and the Golden Globe Award.

Now let’s move another year ahead, [to] April 21, 1960. Brazil inaugurated its futuristic new capital city of Brasilia. It was the brainchild of its then-president, Juscelino Kubitschek, or as he was known to Brazilians, “Jota Ka” (JK). His motto, “Fifty years in five,” was his promise to bring the Brazilian nation into the twentieth century. I think those five years are just about up. In November of 1960, another JK – JFK to be exact – was inaugurated president of the United States. It was part of that Kennedy administration’s cultural exchange program that in March of 1961 the US State Department sent Charlie Byrd on a three-month, 18-country tour of Latin America. The trio included Charlie Byrd, the guitarist, Keter Betts on bass, and our guest Buddy on drums. The year after that, right Buddy, remember the date … 1962, Jazz Samba?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Oh, yeah, February 13. Three days before my birthday.

Josmar Lopes – Happy belated birthday! Jazz Samba was recorded at the All Souls Unitarian Church right here in D.C. The album was released on April 20, 1962 and it charted for 70 weeks. It sold half a million copies in 18 months. It was the only jazz album ever to top the pop and jazz Billboard charts. And in 2010, Jazz Samba was officially inducted into…

Buddy Deppenschmidt – The Grammy Awards Hall of Fame.

Josmar Lopes – That’s right. A little bit later in 1962, if any of you remember, in October of 1962, the Missiles of October. We had the Cuban Missile crisis, with tensions heating up between Russia, Cuba, and the US. Buddy, it’s amazing that all this history was packed into just those four years: 1958 to 1962. And here we are, facing another World Cup, coincidentally, in a few weeks. I don’t know if that’s going to go off, but soccer being soccer it’ll come off all right. Brazil should score a goal in that one. But Buddy is still with us, thank goodness. And my first question to you, Buddy, about all this activity that was going on, how did a drummer from Philadelphia get swept up in this grandiose project with the State Department to visit 18 countries in three months?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – I was working with a piano trio, the Newton Thomas Trio, a very good trio. And we had played Birdland, the Blue Note in Chicago. We were doing the Virginia Beach Jazz Festival and Charlie Byrd’s Trio was one of the groups that played in the festival. And Dave Brubeck was on the festival, and little did I know that fifteen years later I’d end up studying with his drummer. But Charlie heard us and we did very well on the festival. In fact, we brought the house down and it was a standing ovation and all. And we weren’t supposed to be big deal. The Brubeck group was supposed to be star of the festival and, all of a sudden, here we are getting a standing ovation. I was overwhelmed and I was about only 24 at the time.

Two nights later, into the club walks Charlie Byrd, with his drummer and his drummer’s wife and his wife. His wife slips me a note under the table. I didn’t know what to think, you know. So I said, “Pardon me, I have to go to the restroom.” And I got up and went into the restroom and I read the note, and it said: “If you’re interested in playing with my group, give me a call at this phone number and we can get together in Washington, D.C. We’ll run over a few tunes and see if it will work.” He wanted Keter’s okay, wanted to make sure Keter was happy with it. And he wanted to make sure that I would work out for him.

As it worked out, I stayed with him for about three years. It was a hard decision to make, to leave the Newton Thomas Trio, because I was quite happy with him. That’s how it all happened. All of a sudden I find that here I’m being asked to go to South America. Charlie says, “How much do you want to go to South America?” I said, 24 years old, “I don’t know. What’s the going rate for drummers to South America these days?” Because I didn’t know. So we went down there and we had a great time. The people were wonderful. I hung out mostly with the local musicians and learned a lot.

Josmar Lopes – Did you get prepped by the State Department prior to going there? Did they give you pointers on how to deal with the locals…

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Oh, yeah….

Josmar Lopes – … because of all these political things going on?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Yeah, they said, “You’re going to have a lot of press conferences, be careful what you say. They may try to entrap you into saying things. And then put it in print in the newspaper and distort the facts a little bit.” So we had to be really careful about what we said and how we acted, our manners. We were briefed in every city, “You don’t do this in this country. It’s against the customs.” It might be something that was perfectly acceptable in the United States, and we wouldn’t mean any offense by it. But we could do something innocently and cause a big deal, a big scene. So, yeah, we got briefings in just about every city.

Josmar Lopes – How soon after you joined the Charlie Byrd Trio did you set off to South America?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – It wasn’t very long at all. It was a matter of maybe weeks, not even months. The funniest part of it is that the very first night that I played with Charlie, he said, “Have you ever recorded?” And I said, “Oh, yeah, I made tapes before.” He said, “No, I mean commercial recordings.” Then I said, “Well, not really.” He said, “Well, we have a record date on Saturday.” And that was four days away. “You’re kidding!” And he said, “Don’t worry, we’ll play the tunes every night and by the end of the week you’ll know them.” He said, “We get turnover with the crowds, so we’ll play them early on, then we’ll play them again later in the evening. So you’ll get to play everything at least twice a night, for four nights.”

Josmar Lopes – You think you’d get it into your head by then.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Yeah, and it turned out just fine, it was a great record date.

Josmar Lopes – So, let’s talk about your trip to Latin America. Which country did you hit first?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Venezuela. We played in Caracas, and then we had to do, uh, well, first of all we didn’t get much of a rest. We got a couple of hours sleep, and then we had to get our plane very early in the morning. After the concert, I was thinking, “Oh, wow, I’m going to be able to go back to the hotel and lie down and get a little rest.” There was a command performance for President Betancourt, and we had to go over to the president’s palace. There were all these guys with machine guns lined up on either side of the walkway. I didn’t have to lift the drum. Everybody was grabbing my stuff and carrying it in. And I play with no shoes on when I play drums. I had my shoes off and I was playing in my stocking feet. People were staring at my feet thinking, “This is impolite. You just don’t take your shoes off in the president’s palace.”

Josmar Lopes – I’m sure they didn’t mind once you started playing.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – I explained, “Well, you know, think of it this way: if you were a piano player, would you like to play with gloves on?”

Josmar Lopes – No.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – You want to feel the keys. And I wanted to feel the pedals. I always played with no shoes.

Josmar Lopes – You can keep them on for today, Buddy.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – I am, I am!

Josmar Lopes – When did you go to Brazil, afterwards?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Actually, we were only in Venezuela that one night. The next day we left and went directly to Brazil.

Josmar Lopes – Did you start in the north and work your way down south?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Yes. We were in eight cities in Brazil. We were in Brazil for two weeks. It was in Salvador, Bahia, that I met a judge, Carlos Coqueijo Costa.

Josmar Lopes – Tell us about that. That’s your first encounter with Brazilian music, wasn’t it?

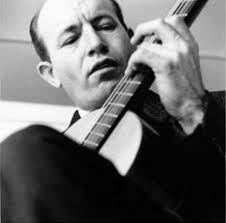

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Yeah, he invited us all over to his house for dinner. And then after dinner, everybody got the guitar and passed it around. And everybody in the family played well. His son was a piano player, but he also played guitar well, and a drummer. They put on João Gilberto records and he put a cardboard album jacket between his knees and started playing brushes on it. Unbelievable brushes! I thought, “Wow, this is really great stuff.” So, I think we went out the very next day, Keter Betts and I went out the very next day and bought the records of Gilberto. There were only two at the time. We bought both of them. We’d go to the [American] Embassy and borrow a little portable record player and play the records in our room. Keter would bring his bass down to my room and we would rehearse. We got it together before we ever finished the tour. We were just anxious to get the sound.

Josmar Lopes – Did you show them anything about American rhythms, American jazz drumming, or the style?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Oh, yeah, we hung out a lot with the musicians.

Josmar Lopes – You didn’t go to any of those State Department dinners or banquets or anything?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – I went to a few, but they get boring pretty fast. And I don’t like martinis for lunch – for breakfast and lunch, and by the time we would get up it would be lunchtime already for most people. We hadn’t had breakfast yet. You don’t want to go off to a cocktail party and start drinking martinis on an empty stomach. So, yeah, we hung out with local musicians more than cocktail parties. I mean, the cocktail parties went on forever. Eventually, I just started bowing out.

Josmar Lopes – Probably a good move, I’d think.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – I’d have to get some rest.

Josmar Lopes – You wound up, after that occasion … Well, I might have mentioned to you that that judge that you met, Carlos Coqueijo Costa, was a friend of Vinicius de Moraes. He had even written a song that João Gilberto recorded, believe it or not, in 1973. It was called “É preciso perdoar” (“It’s Necessary to Forgive”). So that judge, the reason the family was so musical, was that he had music in his veins.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – And he never mentioned any of these things, you know.

Josmar Lopes – Ah, Brazilian modesty. Anyway, you found your tour going to Porto Alegre, in the south of Brazil. Now, that led to a very interesting encounter. I’m sure the audience would like to hear about that.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – After our concert in Porto Alegre, this young girl comes up. She was probably of high school age. And she said, “We’d like to invite you over to the house for lunch tomorrow.” And I said, “Well, I’m married and have a couple of children.” And she said, “We’d like to invite you over to the house tomorrow anyway. We’re going to play João Gilberto records.” I said, “Well, Keter and I just went out yesterday and bought those. And we’ve been listening to them.”

Josmar Lopes – Here’s Malu and a picture of Buddy teaching them the drumming, and vice versa.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – They were teaching me more than I was teaching them.

Josmar Lopes – There you go! That’s her in the middle.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – So anyway, she said, “Well, then, we’ll teach you how to play the rhythm. My boyfriend is a drummer.” That was Mutinho, and he was a drummer, and also played, everybody played the guitar very well down there. It was just like you grow up, you learn how to play the guitar, just like you learn how to hit the baseball in this country, since you were a little kid.

Josmar Lopes – That’s a good analogy.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – So everybody, the first thing you wanted to do was learn how to play the guitar. When you were old enough that we could trust you to hold it and you wouldn’t break it, now we’ll show you how to play this chord and that chord. So everybody just knew how to play guitar, everyone. I didn’t meet anyone down there that couldn’t play guitar.

Josmar Lopes – So there you are, surrounded…

Buddy Deppenschmidt – We’re surrounded, her father took off from work that day. Her grandmother was there, all her brothers and sisters were there. Her boyfriend was there, and all her friends from school. It was quite a get-together. They just sat me down and showed me how to play that rhythm.

Josmar Lopes – Did you show them some American rhythms?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Not that day, no. But I mean, there were many occasions where I would stay up all night with someone, a drummer, who couldn’t speak a word of English and I didn’t speak Spanish or Portuguese. We would turn a trash basket upside down and then turn the ice bucket upside down, have an ashtray and with a cocktail stirrer. He would show me rhythms and I would show him jazz rhythms. So it was really a cultural exchange tour, for sure.

Josmar Lopes – In the other countries you went to, did they impress you as much as the sounds that the Brazilians had made?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – They were all interesting, but I can only recall one rhythm that I fell in love with down in Colombia. It was taught to me by a drummer from Argentina.

Josmar Lopes – Oh, that makes sense!

Buddy Deppenschmidt – He was playing in the hotel room we were staying, his name was José Signo. He and I corresponded quite a bit. He would even send me rhythms written out on paper. But he taught me this one rhythm called the matecumbe, which was really an interesting rhythm.

Josmar Lopes – You demonstrated that for the [Jazz Samba] symposium yesterday.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Yeah, I did.

Josmar Lopes – Fascinating!

Buddy Deppenschmidt – It’s an unusual rhythm.

Josmar Lopes – I’ve never heard anything like that.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – It has one cowbell beat on the first beat of every measure, just one beat. And “konk,” two, three, four, boom “konk,” two, three, four, boom “konk …” And so you hit one bass-drum beat and one cowbell beat. And then, with your drumsticks, if these were the rims of your drum, they’d go “click, click,” you’d go “bam, click, ka-tick, ka-boom, ka-tick kam, ka-tick, ta-boom-boom, ka-tick boom-kam.”

Josmar Lopes – Sounds like rap.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – So you’re hearing: “One, two, three, four, boom bah, two, three, four, boom-bah, ka-tick, tick-ka, ka-tick, tick-ka, ka-tick-tick-ka boom boom, ka-tick-ba, ka-tick-tick-ka-boom-boom, ka-tick.” Then it was such an interesting rhythm. And all the parts were very simple and sparse, but when you put them all together and at the same time, there was a lot going on there.

Josmar Lopes – A lot going on here!

Buddy Deppenschmidt – And there was nothing even close to it. I never heard anything like it. I used to pay all these Arthur Murray dance parties when I was growing up. And I liked Latin rhythms a lot. I’d get those jobs because I could play the rumba, the mambo, the samba, oh, what was that called, the paso doble, the tango. And it was Arthur Murray dance party, so it was all about doing the dance steps. You had to know how to play all the different rhythms to all the dance steps. All those waltzes … It was good experience for the drummer, because you got to use your entire repertoire of rhythms.

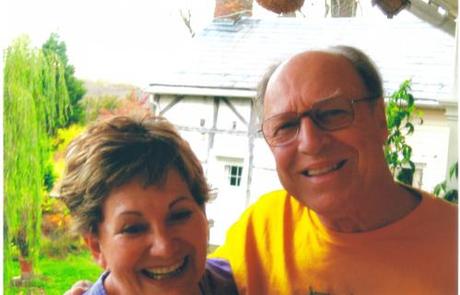

Josmar Lopes – Getting back to Malu — Maria de Lourdes Regina Pederneiras, [but] everyone called her Malu. The young girl you met, did you have a reunion with her sometime later in life?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Yes, she came up to visit Margie [Marjorie Danciger] and me. Margie is my best friend and she also … well, I would call her the best manager in the world, if you want to call her a manager. She sure manages me. Anyway, Malu came up and visited us after 50 years. The funny thing is, a few years before we were talking about Malu, and Margie said, “Why don’t you call her up?” I said, “I don’t have her phone number.” She said, “Well, I’ll get her phone number.” And I don’t know how she did it, but she got online and she got the phone, and she talked to information. She ended up getting the right phone number and I called Malu and left a message. She couldn’t believe that I had found her phone number, living up in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and finding her phone number in Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Josmar Lopes – I’d like to show a picture of you and Malu, in October of 2010. These are the two friends after almost 50 years.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Yeah.

Josmar Lopes – She looks the same.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – I don’t know if I should read you this, because I’m not much of a singer.

Josmar Lopes – Before [you] do, let me tell you what Malu said of your ultimate success.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Oh, yeah. Why don’t you read that thing that she sent to me.

Josmar Lopes – I’ll tell you, she wrote here at the time that she was a fifteen-year-old girl. Yup, “I was just a fifteen-year-old schoolgirl who loved jazz and played the piano and sang bossa nova.” As a matter of fact, João Gilberto was a very close friend of her uncle. He was single and lived with his parents. There are a lot of funny stories of João Gilberto being locked in the bathroom and playing guitar all night. He was a night owl and slept all day. But she came down and saw the Charlie Byrd Trio play in Porto Alegre, and her English teacher recommended it to her classmates. She attended the show. She said here that “there was a good looking young man playing the drums. He looked so American, and was so absorbed by the music as he played. And he played so well that when the show was over I climbed up to the stage and spoke to the lady.” That was Ginny Byrd, Charlie Byrd’s wife – she was doing the singing. She was singing “Cry Me a River,” and she wrote down the lyrics for Malu and she loved it.

Then she found out that you were 24 years old and married and decided to try to make friends with you. “An American musician. Imagine, and he had such good manners and was welcoming. I told him that I knew João Gilberto and that I had a friend who was a drummer and could teach [Buddy] the bossa nova beat.” You seemed quite interested, so she invited you to have lunch with the family the next day and invited Mutinho along, the drum player, and that’s what happened. Years later, this is what she said 50 years later when you picked up the conversation again and the relationship: “All of this may not have happened if we hadn’t done what we did.”

Buddy Deppenschmidt – That’s so true. And she’s just as important a player as I am in this whole picture. Because if it hadn’t been for her, I wouldn’t have even known how to do this. And probably if it hadn’t been for my intense interest, we wouldn’t have done that. So, I was obsessed with it. I just did everything but hit Charlie over the head to make him do this thing, and finally … Charlie’s wife is the one who really convinced him to do it. I figured that was the best way to get to Charlie, it was through his wife rather than through Keter. Keter tried, but Charlie didn’t seem that excited about it at the time. And he had a reputation for playing the classical guitar and bluesy, kind of jazz stuff on the classical guitar. He figured, “Well, I better stick with this because it’s working so far. And I was saying, “No, this is just perfect for you, this is guitar music and you play guitar. You just got back from South America, and it would be so timely to do this now, rather than wait and have someone else do it. Why don’t we do it?”

Josmar Lopes – Whose suggestion was it to bring Stan Getz into the project?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – It was my suggestion to bring Stan Getz in. But Ginny really is the one who talked [Charlie] into doing it. Fortunately, Ginny listened to what I had to say and many a night we would sit there in the booth, while Charlie was doing his classical set. I would say, “Look, Ginny, tell him he should do this. This is going to be a great thing for him.” I didn’t know it was going to be that great, but it really turned out to be a very good thing for him. It was good all the way around, it was good for everyone. I wouldn’t be sitting here today if it hadn’t been good for me, too. So I have to admit that it was good for all of us.

Josmar Lopes – Who was the alternative to Stan Getz, if you couldn’t get him to do Jazz Samba?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – I thought that the only other person that I could think of who might do it well would be Paul Desmond.

Josmar Lopes – The Dave Brubeck Quartet…

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Yeah. I had a lot of Dave Brubeck records that I listened to Paul’s solos, and they were nice and fluid and loose and lyrical. But Stan was my first choice. I thought he would be ideal. As it turned out we did it with Stan. But I was thinking that, you run into some problem with the record company and they don’t want to let their boy record with you, then that would be a good alternate playing.

Josmar Lopes – Speaking of music and lyrics, I think you have a little song of your own.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Yeah, I wrote this for Malu when she came to visit.

Josmar Lopes – Based on “One Note Samba” (“Samba de uma nota só”)?

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Yeah, it’s based on the “One Note Samba.” And if you’ll forgive my poor vocal quality, I’ll try to sing it for you.

Josmar Lopes – Oh, Buddy, here’s JazzTimes, the magazine that the original article, “Give the Drummer Some,” appeared in, which finally gave you credit for bringing the Brazilian beat to American ears. What I’m going to do is accompany you, your rhythm section, beating on top of Stan Getz’s head.

Buddy Deppenschmidt – Oh, my God … Okay, well, here it goes. I’ll give you four beats:

Seems that more than 50 years have past

Since the day I saw you last

You shared your music and your song

This reunion took so long

Tom Jobim, Gilberto and Brazil

Seems somehow I just can’t get my fill

Of the samba rhythm, what a dance

You sparked a musical romance!

When I got back to the States

I surely knew that I was on a mission

No time for fishin’

Even though I made it happen

I guess drummers just don’t get commission

So keep on wishin’

Though ‘t was not authentic, just our version

Jazz and samba started mergin’

I guess we helped to spread the word

And bossa nova sure got heard

Now today the year’s two thousand ten

We’ve a friendship which will never end

And the message that I want to say is

Bossa Nova’s here to stay!!!

So that kind of tells the whole story … in one chorus.

Josmar Lopes – And on that note, let’s have a round of applause for the man who brought the Brazilian beat to American ears!

With gratitude and appreciation to William Henry “Buddy” Deppenschmidt Jr., for his kindness in allowing the use of our interview to be published on this blog site.

Copyright © 2015 by Josmar F. Lopes