Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush[Pauling and the Guggenheim Foundation]

Linus Pauling and Henry Allen Moe, Secretary of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, lived on opposite coasts but built a close relationship through their shared Guggenheim responsibilities. Over the years, the two spent time at one another’s homes and showed genuine, continuing interest in each other’s families and well-being.

Because of their professional relationship, which mostly involved making judgments on the granting of Guggenheim fellowships, the two also had moments of disagreement. Some of these conflicts emerged out of disputes that had nothing to do with the Foundation, the first arising near the close of World War II and concerning the 1945 Bush Report.

In July 1945, Vannevar Bush, the Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, published a response to a request issued by President Franklin Roosevelt. The President had tasked Bush with providing guidance on the best ways to promote science in service of military, medical, public, and private organization. He also wanted Bush to find a way to identify scientific talent in order to maintain the levels of research that had been arrived at during the Second World War. Four committees informed the compilation of Bush’s final report, with Pauling serving on the Medical Advisory Committee and Moe heading the Committee on Discovery and Development of Scientific Talent.

In his cover letter to Roosevelt, Bush acknowledged the importance of research in the social sciences and humanities, but expressed that he did not interpret his original charge as needing to address those areas of study. Moe did not think this was a good idea. In his final committee report, Moe warned against the government steering all of its resources and talents towards promoting the natural sciences and medicine, believing that to do so would ultimately harm the country and the sciences themselves. (“Science cannot live by and unto itself alone,” he wrote.) Because of this disagreement, Moe refused to issue a public endorsement of the Bush Report.

In November a group of scientists – including Pauling – who clearly believed otherwise created the Committee Supporting the Bush Report. This group wrote to President Harry Truman mostly to speak out against proposals made by West Virginia Senator Harley M. Kilgore, and especially the idea that a new program of post-war research support be headed by a single individual or by political appointees. The letter also stated that, despite Truman’s recent comments to the contrary, including the social sciences in the post-war program would be a “serious mistake.”

When Moe saw the letter, he wrote to Pauling, “I am sorry to see that you signed the letter to President Truman for the Committee Supporting the Bush Report!” Pauling was surprised to learn this as he had note yet heard any arguments against the letter and had also not noticed that Moe had declined to add his name. Pauling admitted that he had harbored doubts about the social sciences paragraph, and in fact confided that the language had been softened as a result of objections that he had expressed.

As Pauling thought about it more, he came to further regret his actions. As he admitted to Moe, he had also sent letters to his own Senators and Representatives that contradicted the letter to Truman. “My position as a signer of both documents,” he confided,” is indefensible.”

I became a signer of the letter to President Truman partially through an error in judgment on my part and partially through a misunderstanding about the nature of the revision of Section 8 [the social sciences language] of the letter. I have been hoping that nobody would discover that I have supported both sides in the argument about social sciences, and that the sole effect of my experience would be to educate me.

While this disagreement ended up a minor one with Pauling admitting himself in the wrong, it would not be the last conflict between the two.

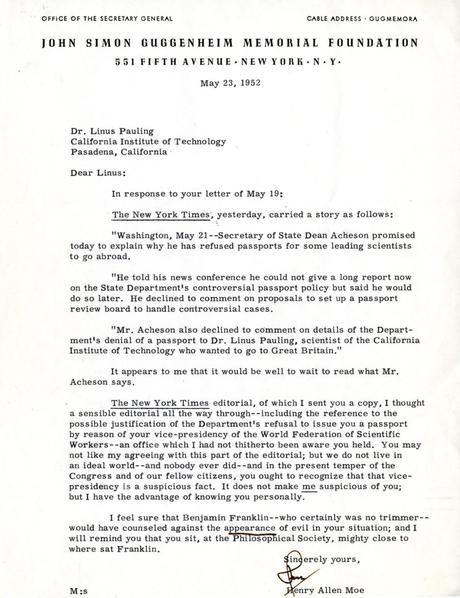

In May 1952, knowing that Pauling was encountering difficulties with the U.S. State Department’s passport division, Moe wrote to pass along a few details from a New York Times article that he had seen. The article noted that Secretary of State Dean Acheson would explain why passport applications submitted by several leading scientists had been denied, but that he seemed less inclined to go into detail about Pauling’s case.

With this, Moe also sent a copy of a Times editorial that he thought reasonable. The opinion piece argued that Pauling’s passport be refused because of his position as Vice President of the World Federation of Scientific Workers, an affiliation that caught Moe by surprise. As Moe explained,

You may not like my agreeing with this part of the editorial; but we do not live in an ideal world – and nobody ever did – and in the present temper of the Congress and our fellow citizens, you ought to recognize that the vice-presidency is a suspicious fact. It does not make me suspicious of you; but I have the advantage of knowing you personally. I feel sure that Benjamin Franklin – who certainly was no trimmer – would have counseled against the appearance of evil in your situation; and I will remind you that you sit, at the Philadelphia Society, mighty close to where sat Franklin.

In his reply, Pauling took pains to note that, when he was originally questioned, the State Department had not asked him about this affiliation, and that furthermore, his proposed travel had nothing to do with the organization. Even so, Pauling explained, he had only recently become affiliated with the group as he was nominated by the American Association of Scientific Workers to be Vice President of the World Federation the previous year. He never received any notice as to whether he had actually been elected or not, only a notice that the board was to meet in England in March. Pauling hesitated in responding because of the short notice and his own lack of clarity about his standing. Then the British government stopped the meeting from happening, at which point he believed the whole conversation moot.

As further justification of its irrelevance to his case, Pauling added that the World Federation had been founded by the Association of Scientific Workers in Great Britain, was comprised of sixteen organizations from fourteen countries, and was recognized by the United Nations as a non-governmental organization. Its purpose was to promote peaceful applications of science and to push for international scientific cooperation in accordance with UNESCO. None of these aims struck Pauling as being un-American.

Pauling likewise argued that neither the British nor the American associations were “communist-dominated,” though branches in other parts of the world – with which Pauling had only a passing acquaintance – may have been. The World Federation had also made an effort to increase participation by non-Communist nations, but strove to do so without cutting off ties from Eastern Europe or Asia.

After the World Federation meeting had been canceled by the British government, Pauling wrote to the American Association that he no longer wanted to be considered for Vice President. Regardless,

It seems to me that international organizations of this sort constitute the best hope that we have for the future. I feel that international organizations of scientists could be especially effective. The Iron Curtain and what might be called the [Senator Pat] McCarren Curtain seem to operate more strongly against scientists than against other people.

Moe does not appear to have replied to Pauling’s letter, but once Pauling was able to obtain a passport and travel to Europe, Moe wrote again to learn more about his trip. Pauling responded that it had been a success. Notably, on his journeys through France, England, and Scotland, he had been able to speak with most of the people working on protein structures that he would have otherwise seen at an earlier Royal Society conference that he was unable to attend because of his passport troubles.

As an outcome of these conversations, Pauling had resolved some difficulties that he was encountering with his proposed structure for hair, horn, fingernails, and similar proteins. Pauling expected that he would have enjoyed similar results had he been able to go to the Royal Society meeting, but that a breakthrough of this sort would have required many months work had he not been able to go to Europe at all. The tenor of this exchange leads one to conclude that the conflict between Pauling and Moe had been extinguished.

Pauling’s passport difficulties happened early in the same year that the House of Representatives Select Committee to Investigate Tax-Exempt Foundations and Comparable Organizations, also known as the Cox Committee, requested information from the Guggenheim Foundation. While Pauling and Moe were able to reconcile their differences peaceably around the Bush Report and the World Federation of Scientific Workers, the Cox Committee and the stress surrounding it would bring up issues that were much more difficult to resolve.