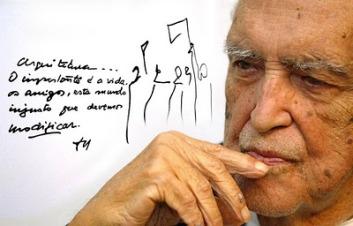

Oscar Niemeyer, 1907-2012

On Wednesday, December 5, 2012, the world mourned the passing of Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer at age 104. The way that Niemeyer seemed to talk about himself and his achievements, one would think that he planned to live forever – and in a way, he will. Let me explain.

An architect is, generally speaking, not the sort of individual that inspires people to great passions. No, they tend to be plain old, “down to earth” folk, although in Ayn Rand’s novel, The Fountainhead, her lead character Howard Roark (an architect) is anything but down to earth. As interpreted by Gary Cooper in the 1949 film version, Roark works up a steamy head of lather and a fair amount of sweat, and not just over some old buildings (I believe his co-star, the lovely Patricia Neal, had something to do with that).

Nevertheless, Niemeyer’s place in forging a modern Brazilian nation is firmly secured, what with his imaginative contributions to the country’s futuristic capital city of Brasília. He also designed her Our Lady of Aparecida Cathedral, which resembles an upside-down crown of thorns – unusual, in that Niemeyer was an avowed atheist as well as a die-hard communist sympathizer. No matter. The old saying, “Do as I do, not as I say,” comes to mind here in properly assessing his life and work.

Niemeyer did bring life back to staid forms. You can say that he saw the benefit that curves possessed over straight lines; in addition, he gave form to what was arguably the tired and the formless — see his Rio Sambadrome if you have any doubts of his abilities. Indeed, he took a well-worn architectural turn of phrase, “form follows function,” and twisted it around to read “form follows feminine,” which tells you more about Niemeyer the man than you may have wanted to know.

He lived so long that he buried both his first wife and his one and only daughter. You can read about his range of accomplishments in any of this past week’s obituaries. Still, I would like to draw your attention to the superb one written by one of my favorite print journalists and television commentators, the Washington Post’s Eugene Robinson (http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/eugene-robinson-oscar-niemeyer-soared-as-an-architect).

What went unstated in all these glowing postmortems, however – and what most of the architect’s many admirers may not even have known about him – is Niemeyer’s impact on Brazilian theater, vis-à-vis his revolutionary set designs for the musical play, Orfeu da Conceição (“Orpheus of the Conception Hills”), written by two of Brazil’s leading artists, poet Vinicius de Moraes and composer-musician Antonio Carlos “Tom” Jobim.

The work premiered on September 25, 1956, at Rio’s Teatro Municipal. Here is what I had to say about Niemeyer’s participation in the venture:

“Oscar Niemeyer, a master of curvilinear shapes and forms (who incidentally marked his stage debut with this piece), was himself strongly influenced by classical antiquity, as was Lila Bôscoli de Moraes and her designs for the show’s captivating gowns. Beyond this, Niemeyer’s plans for Brazil’s futuristic new capital city — by filling its ‘vast empty space’ with ‘sensuous white curves in glass and concrete’ — were the visible manifestations of what Tom and Vinicius aurally tried to capture with their epicurean taste in tunes.”

Now here is what Niemeyer himself said about his involvement:

“Invited by Vinicius to design the sets for Orfeu da Conceição, my first reaction was to decline, for I had never worked for the theater before and the subject seemed rather complicated to me. But my friend insisted, so I accepted the challenge which, fortunately for me, became more of a pleasure.

“When I began the design of the sets…, I decided not to make any preconceived notions, considering instead the blocking of each scene and the poetic gist of the text. Hence the absence of realistic elements and the sketchiness of the scenery, the idea being to preserve the climate of lyricism and drama, at once so fantastic, that Vinicius created and that leaves the characters hovering in space, entirely at the mercy of their passions.” (From the Songbook Vinicius de Moraes: Orfeu, published by Jobim Music, 2003)

The play inspired the passions of French filmmaker Marcel Camus, who went to Brazil to direct the Academy-Award winning Black Orpheus, his own cinematic paean to the beauty of Rio de Janeiro. Most of the music for the film was provided by Jobim (along with Luiz Bonfá). What fans of Vinicius and Jobim’s song output may not have realized is that Jobim first took up architecture as a profession, only to drop it in favor of music. He toured the site for the proposed Brasília project with his songwriting partner Vinicius and Niemeyer in tow. This later bore fruit in a major new composition, the Sinfonia da Alvorada, from 1961.

Barely a year later, as poet and musician were comfortably ensconced outside the Veloso Bar in Rio, a teenager by the name of Heloísa Eneida Menezes Paes Pinto (later Pinheiro) crossed their path. She became the inspiration for the entranced pair to write their most wittily sensuous and widely recorded song hit, “The Girl from Ipanema.”

If “form follows feminine,” as Oscar Niemeyer so claimed, then let the above incidents serve as “concrete” proof of that sentiment. And as far as inspiring passion goes, Niemeyer had plenty of it to spare. May he be granted eternal rest from his labors… †

Copyright © 2012 by Josmar F. Lopes