Shelby County, Alabama

The legal and political worlds have been abuzz over the past 24 hours about the U.S. Supreme Court's decision yesterday to overturn a key section of the Voting Rights Act in a case styled Shelby County v. HolderImplied in the ruling is the assertion that Shelby County, Alabama--and places like it--are more enlightened now than they were when the Voting Rights Act was passed almost 50 years ago. So that raises these questions: What kind of place is Shelby County, Alabama, in 2013? And in terms of justice issues (such as voting), should the public be confident the rule of law will prevail in this burgeoning area south of Birmingham?

As a resident of Shelby County since 1989, I feel qualified to take a crack at those questions. What are my answers? Well, Shelby County is a prosperous, pretty place that features lots of gorgeous trees, mountains, and bodies of water--I can throw a rock from my backyard and almost hit the natural splendor of Oak Mountain State Park. The county, especially in the northern section closest to Birmingham, features numerous fine places to shop and dine, with some of the most attractive neighborhoods you will find anywhere.

But what about those pesky justice issues? In that regard, Shelby County is a cesspool. The county seat is in a little hellhole called Columbiana, and when you take one step into the city limits, it's as if you've entered a time warp and gone back to . . . oh, about 1912.

Experience has taught me that almost all of Shelby County's "justice infrastructure"--the courts, the sheriff's office, the county commission--is hopelessly corrupt. Have things improved here on the racial front since 1965? I have little doubt that the answer is yes. But can citizens of any color--especially those who somehow are seen as different, or outside the suburban, conservative mainstream--expect to have their legal rights protected? The answer is a resounding no.

I know that with certainty because of first-hand experience, which I have written about extensively on this blog. I also know from reporting on the legal nightmares of others who have been railroaded in the Shelby County "justice system."

Before I provide details about what I have witnessed in Shelby County, let's consider the words of journalist Greg Palast about yesterday's SCOTUS decision. In a piece at Truthout titled "Ku Klux Kourt Kills King's Dream . . . ," Palast writes:

The problem is not that the court majority is racist. They're worse: they're Republicans.

We've had Republicans, like the great Earl Warren, who put on the robes and take off their party buttons.

But this crew, beginning with Bush v. Gore, is viciously partisan. They note that "minority candidates hold office at unprecedented levels." And the Republican Supremes mean to put an end to that. . . .

And when they say "minority," they mean "Democrat."

Because that's the difference between 1965 and today. When the law was first enacted - based on the personal pleas of Martin Luther King - African-Americans were blocked by politicians who did not like the color of their skin.

But today, it's the color of minority voters' ballots - overwhelmingly Democratic blue - which is the issue.

Palast's words resonate with me, and here is why: As a white male, I fit the primary racial mold in Shelby County. But as a liberal Democrat, married to a liberal Democrat, I am very much a political outsider. And in fighting various court battles for 12-plus years, I've learned that my status as a political outsider means my constitutional rights to due process and equal protection are subject to being trampled.

Sherry Carroll Rollins, a central figure in the Rollins v. Rollins divorce case, has learned a similar lesson. Her case was decided in Shelby County--even though jurisdiction was established in Greenville, South Carolina, the case was litigated there for three years, and it could not lawfully be moved--and has been the subject of dozens of posts here at Legal Schnauzer.

The victims of former Shelby County teacher Daniel Acker Jr. also suffered because of a dysfunctional justice system. Acker, the son of a long-time Shelby County Commission member, faced allegations of sexual abuse in 1992. But with a number of community groups coming to his support (especially from churches), a grand jury failed to indict him and he kept his job. Some 20 years later, Acker confessed to molesting more than 20 girls during his teaching career, and he now is serving a 17-year prison sentence.

What about my wife and me? Let's consider just one event from our experience. We've had the full ownership rights to our house stolen by a corrupt cabal of lawyer William E. Swatek, Sheriff Chris Curry, and Circuit Judge Hub Harrington. I outlined the key issues in a post titled "Going On The Attack Against The Thugs Who Stole Our House."

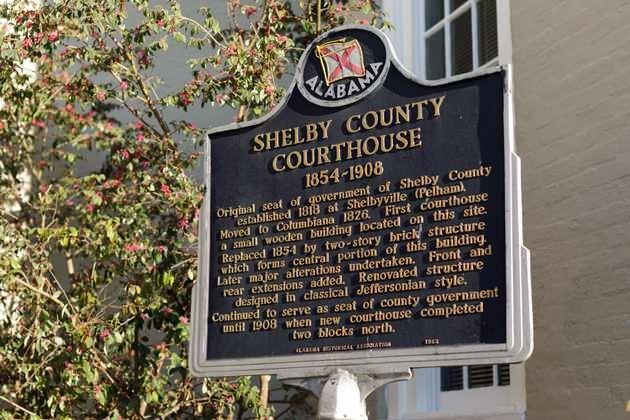

What was the fallout? We still live in our house, but a portion of the rights were auctioned off on the steps of the Shelby County Courthouse in May 2008, and Bill Swatek currently holds a sheriff's deed on our property--even though more than a half dozen provisions of black-letter law say that can't happen.

I explained all of this in a post that was written just hours after the auction took place. You can check it out here.

For posterity's sake, we captured the auction itself in living color. And it makes for particularly interesting viewing, in light of yesterday's SCOTUS decision that found--in so many words--that all is sweetness and light in Shelby County, Alabama.

My wife and I know that is a load of horse feces. We invite you to click on the video below and see for yourself.

(To make matters particularly surreal, the sheriff's deputy in the video below is named Bubba Caudill. I didn't make that up, and he's not a character from central casting for a Smokey and the Bandit movie. It's his real name, and he's a real deputy in Shelby County, Alabama, the place that spawned yesterday's ruling in Shelby County v. Holder.)