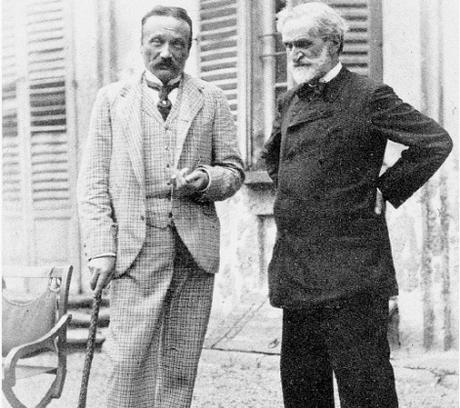

Arrigo Boito & Verdi (Photo: Achille Ferrario, Gazzetta di Parma, 1892)

Arrigo Boito & Verdi (Photo: Achille Ferrario, Gazzetta di Parma, 1892)A Poet’s Work is Never Done

Arrigo Boito would never have been Verdi’s choice for a librettist, or for anything else he might have had in mind, were it not for their mutual love of Shakespeare.

The crotchety Italian master, whose initial attempt at tackling a play by the Bard of Stratford-upon-Avon, the opera Macbeth (1847, revived for Paris in 1865) met with audience acclaim if not widely favorable reviews, longed to set Shakespeare’s King Lear to music. The closest he came to scaling the Elizabethan heights, however, was with Rigoletto, written in 1851 to words by the poet Francesco Maria Piave.

Piave was Verdi’s most frequent collaborator. Over the course of two decades, the Venetian-born stage director and jack-of-all-trades (according to author William Berger) had supplied the cantankerous Bear of Busseto with texts to no less than nine of Verdi’s stage works, to include Ernani, I Due Foscari, La Traviata, and La Forza del Destino.

By the time of Simon Boccanegra (1857), the so-called Middle Period of the composer’s output, Verdi had pretty much wiped the slate clean of his rivals. His interest in the character of “Simone,” a historical 14th century personage of ignoble repute (a corsair, or “privateer,” he won election as the Doge of Venice), was due mostly to Boccanegra’s intense love for his long-lost daughter Maria, known under the pseudonym Amelia Grimaldi.

Verdi based his opera on another of those blood-and-thunder melodramas by the Spaniard Antonio García Gutiérrez, the same playwright who provided him with silage for Il Trovatore. The dark, unremittingly gloomy tone of Simon Boccanegra, as well as the winding, convoluted plot (similar, in many respects, to that of Trovatore), did not enjoy popular success. The work was mothballed for a time as Verdi undertook the writing of other projects, among them Un Ballo in Maschera (1859) for the Teatro Apollo in Rome; and an early version of La Forza del Destino for St. Petersburg (1862), later revised for La Scala in 1869, with additions by Antonio Ghislanzoni, the future librettist for Aida (1871). In 1867, Piave was sidelined by a stroke and, for the remainder of his life, was unable to take up his trade.

When did Boito enter the picture? In my essay concerning his opera Mefistofele, I discussed Boito’s career, in addition to his involvement with the Scapigliati movement (see the following link: https://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/2016/05/17/mefistofele-ecco-il-mondo-the-devils-in-the-details-of-boitos-opera-part-four/), and his adaptation for composer-conductor Franco Faccio of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. To make a long story short, Boito proved to be a learned man of letters, one with an elegant way with words that struck to the heart of whatever he was writing.

It was soon after Verdi and his wife Giuseppina Strepponi’s return from St. Petersburg, and while maestro Verdi was staying in Paris, that he accepted a commission to compose a musical entry for the London Exhibition. This exercise in alleged European “cosmopolitanism” resulted in the inspirational Inno delle nazioni (May 1862), widely known as The Hymn of the Nations, for tenor and mixed chorus. The verses, which impressed the partisan composer, were written by the young 20-year-old firebrand Arrigo Boito, fresh out of the Milan Conservatory.

A year later, in November 1863, Boito would douse cold water on what would have been an historic musical and literary association. Whether knowingly or not, he decided to badmouth the status quo (and, by implication, Verdi himself) in a brazen toast Boito gave at a banquet in honor of his friend Faccio’s next opera, I profughi fiamminghi.

In a pique of inspired oratory, Boito stood up to recite an ode in which he railed against the older establishment. “Perhaps the man is already born who will restore art, in its purity, on the altar now defiled like the wall of a whorehouse.” According to music editor and critic Paul Hume, “These rousing sentiments might have sounded great to the partygoers, particularly after the first few bottles of the local produce had been opened and downed. To Verdi, however, reading them in cold print a few days later, they reeked of juvenile ignorance. To the man with twenty-two operas behind him they were a personal insult” (Hume, Verdi, the Man and His Music, p. 106). Here, here!

And to most people, hurling abuse at one another, no matter the motives behind them, might have spelled doom toward any effort in establishing further contact — especially for these two obstinate fellows. Would they ever be able to bind up their wounds and seek reconciliation? Not to belabor the point, we are talking about two of the most extraordinary artists under the Italian operatic firmament. Though not by nature a forgiving individual, Verdi nonetheless expressed sincere admiration for Boito’s poetic spirit. And anyone who cherished Shakespeare, as both he and Boito certainly did, could not be all bad.

In the days when Macbeth had failed to impress the critics, Verdi himself once declared: “I thought I had done pretty well; it seems that I was wrong … But to say that I do not know, do not understand Shakespeare — no, by heavens, no! I have had him in my hands from earliest youth, and I read and re-read him continually.”

To Rise and Rise Again

Boito’s name would indeed come up again when, after the disastrous Milan premiere of Mefistofele in 1868, Verdi felt the time was ripe for revisiting the previous La Forza del Destino. Tito Ricordi, son of the founder of the family-run House of Ricordi publishing firm, suggested Boito for the assignment. Although the composer chose Ghislanzoni for the alterations, Boito kept cropping up at the oddest of times.

Years later, Tito’s son Giulio, who became a significant part of the composer’s inner circle (more so than his father had been), approached the aging Verdi with the idea of revamping the failed Simon Boccanegra. By giving Boito the opportunity to redeem himself, he and Verdi could put aside their past differences by applying themselves to a common purpose. For them, there was no higher calling than the preservation of Italian art.

In all honesty, no amount of textual slicing and dicing could possibly help to bring order and clarity to Simon Boccanegra’s unruly plot. The main issue, which Verdi had vowed to confront, was the reintegration of his music into the basic story line; to make text, voice and score flow as one, thus preserving the essence of the drama without resorting to the formulaic scena ed aria e cabaletta, those age-old strictures dictated from time immemorial.

Boito gave Verdi exactly what he wanted — and needed. The refurbished work, while no better dramatically than its predecessor, received its second premiere at La Scala in 1881. It far exceeded the composer and public’s expectations. While still an ominous, brooding piece, Boccanegra boasts some surprisingly innovative passages that light the way toward where Italian opera was going, particularly in the newly conceived Council Chamber scene — one of Verdi and Boito’s most gripping scenes, with a golden opportunity for star baritones to shine.

Other equally invigorating instances can be found in Fiesco’s haunting farewell to his dead daughter early on in the Prologue; in Amelia’s gorgeously evocative opening air to Act I proper; in Boccanegra’s tender outpourings in his duet with Amelia; in the Iago-esque monolog by his adversary, Paolo Albiani; and in Gabriele Adorno’s urgently delivered solo. These examples far surpass many of Verdi’s previous efforts in this vein by transforming the usual stand-and-sing approach into vibrant theater.

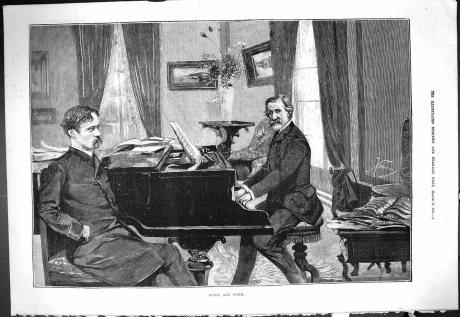

With this accomplishment, and with the future Otello, Verdi found a kindred spirit in, of all people, the poet Arrigo Boito (with a valuable assist from Boito’s close friend and associate, maestro Faccio). In Hume’s words, “If Verdi could be stubborn, Giulio Ricordi could be persistent and Giuseppina ingenious.” The two conspired, to use the proper term, to bring Verdi and Boito toward a closer, if not warmer working relationship. They dubbed their little escapade the “Chocolate Project.” After endless discussions, numerous back-and-forth correspondence, furtive meetings, delays and postponements, amid periods of work and slack and such, eventually the two men warmed up to each other as only artists of the highest order could.

Much time had elapsed since Verdi had given the world what many felt would be his closing statement on the exceptionalism of Italian opera in the four-act Aida. The 16-year interval between Aida (1871) and Otello (1887) — an operatic “drought,” as it has so often been described — was not entirely without musical highpoints. There was the aforementioned reworking of Simon Boccanegra, of course, but prior to that the multiple versions of Don Carlo (premiered in 1867, revised 1872 and 1884), about as somber and foreboding a piece as Verdi had ever produced.

Certainly, one of the most notable accomplishments during this phase, the extraordinarily reverent Requiem Mass (1874) in memory of writer and poet Alessandro Manzoni — with its scorching Dies irae (“Day of Wrath”) section that calls to mind the terrors of God’s Final Judgment — was nothing if not a harbinger of what the Italian master would bring to the crashing opening chords of Otello. The magnificent Storm Scene that begins the opera, if not the entirety of the work itself, is surely one of Verdi’s supreme accomplishments in the unification of plot, music and setting; an exhilarating demonstration of the violence of the natural world run amok.

Those same elemental forces which, in Otello, not only drive the plot forward but are indicative of the title character’s moral failings, are omnipresent as well in the various depictions of the sea in Simon Boccanegra. From the mournful prelude, to the sparkling introductory music to Amelia’s Act I scene, right on through to Simon’s poignant death scene, Boccanegra speaks of the life-affirming aspects of the city — namely, that of Venice and its surrounding islands.

In Otello, the island nation of Cypress, which is the setting for Verdi’s penultimate masterwork, survives the destructive effects of the storm; only to bear witness to more violence in the emotional upheaval evidenced later on by the Moorish general’s brutal murder of his wife, Desdemona. Ah, Shakespeare!

What hath Verdi and Boito wrought? Only the greatest creation under the Italian operatic sun, that is all. Verdi finished the score of Otello on November 1, 1886. He touted this fact in one of his “characteristically pious and friendly” letters to his chief collaborator, Arrigo Boito:

“Dear Boito: I have finished! All hail to us … (and to Him too!!). Addio, G. Verdi”

(To be continued…)

Copyright © 2016 by Josmar F. Lopes