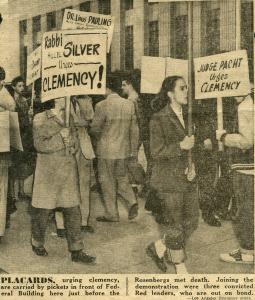

Los Angeles Examiner photo, ca. June 1953. Note the partially obscured placard at left referencing Pauling’s support for clemency.

[Part 3 of 3]

The trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg attracted huge attention from an international audience that found itself polarized over the trial and sentencing of two Americans accused of spying for the Soviet Union. The length of the Rosenberg affair, from its beginning as a news item in early March 1951 through the appeals leading up to the couple’s executions on June 19, 1953, allowed for much public discussion and debate about the legality and morality of the hearing and punishments that the Rosenbergs received.

The question of the couple’s guilt played little role in these discussions – especially after their deaths, when broader focus shifted to the lengthy jail sentence issued to Morton Sobell. One did not have to buy in to the innocence of the Rosenbergs or Sobell to believe that the sentences they received were out of line with sentences issued to past conspirators or spies. Klaus Fuchs, for example, who had admitted to sharing secrets stolen from Los Alamos, received only fourteen years in prison, while confessed spy David Greenglass was sentenced to fifteen years in prison. Greenglass’ wife Ruth, the likely perpetrator of the crimes for which Ethel Rosenberg was executed, was never tried at all.

Those protesting the Rosenberg decision further argued that it had set an ominous precedent for future espionage cases and, as such, had compromised the United States’ standing on the global stage. The affair likewise emphasized the growing fear of Communism, the troubling grip of McCarthyism, and the excesses associated with the Cold War as played out in the US. When the Rosenbergs were sentenced to death, protests of outrage emerged around the world, including condemnations issued by the Pope and the president of France. Despite the cacophony, important actors within the United States government did not reconsider the sentences, as the prevailing belief was that a show of mercy could be construed as weakness.

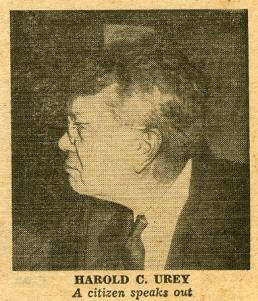

The discord that emerged over the sentences led popular scientists such as Albert Einstein, Linus Pauling and Harold Urey to speak out alongside a broad spectrum of other cultural figures, including Jean-Paul Sartre and Frida Kahlo. Urey, winner of the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1934, was a particularly vocal supporter of both the Rosenbergs and Sobell, and he used his status as a major scientific figure to advance his argument. Urey was a physical chemist who, among other achievements, discovered deuterium through isotope separation and ultimately played a major role in the development of the atomic bomb by working on the enrichment of uranium. He used his expertise as an atomic scientist to specifically argue against the importance of the data that the Rosenbergs had been accused of giving to the Soviets.

But it was not only popular public figures who spoke out; large protests were held outside of U.S. consulates in London, Milan, and Paris and, in February 1953, a New York Times survey reported that the Rosenberg case was the “Top issue in France” at the time. The case resonated in particular with the French due to connections that were drawn between the Rosenbergs and Alfred Dreyfus, a French Jew accused of treason in 1894 whose case served as another instance of public opinion and popular press playing a role in a loyalty trial. As might be expected, the Rosenbergs likewise found support with left-leaning intellectuals and associated publications.

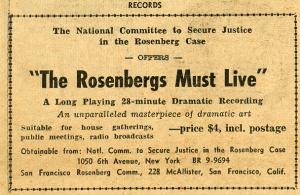

Advertisement from the National Guardian, December 25, 1952.

In August 1951, one such publication, the National Guardian news periodical, published a seven-part series that examined, critically, the ruling handed down at the Rosenberg trial. This was the first paper to do so and the series prompted such a strong response from readers looking to act that it prompted, in October 1951, the formation of the National Committee to Secure Justice in the Rosenberg Case. William Rueben, author of the first article in the series, served as acting chairman of the group, and it was through this committee that Linus Pauling publicly voiced his support for the Rosenbergs and lent his name to the couple’s cause. Over time, branches of the committee or other pro-Rosenberg action groups emerged all around the world, including Britain, France, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, Germany, Ireland, Israel, and parts of Eastern Europe.

A primary tactic of the National Committee to Secure Justice in the Rosenberg Case was to circulate correspondence written by the Rosenbergs from death row to help garner support for their cause. These letters depicted the Rosenbergs as normal people who were trying to do what was best for their children’s future by securing peace and standing up for their beliefs. The letters dealt very little with the specific details of their case or the charges that were made against them. Instead, the releases emphasized the Rosenbergs’ hopes that their death sentences might be reevaluated in an environment devoid of the fear and hysteria that had surrounded them and their trial from the outset. The committee also released a series of pamphlets that encouraged the public to read about the case and to judge for themselves.

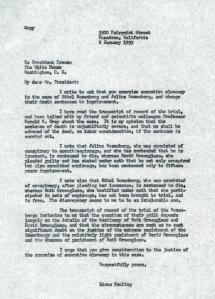

Pauling’s letter to President Truman, January 1953.

Calling attention to the science of the case was another path of support enlisted for the Rosenbergs. In November 1952, the Rosenbergs’ attorney, Emanuel Bloch, issued a direct appeal to a number of scientists, including Pauling, requesting their help. In his letter, Bloch asked specifically that the collection of scientists support his claim – as Harold Urey had done – that the stolen information leaked by the Rosenbergs was not crucial to the Soviets’ development of atomic weapons. Bloch explained that it did not matter if scientists believed the Rosenbergs to be guilty or not; what mattered was whether or not the scientific information they had put into Soviet hands was secret and if it was crucial to advancing Moscow’s development of an atomic weapon.

Pauling chose to go a different way in his pro-Rosenberg activism. Rather than focusing on atomic science in his statements, Pauling instead emphasized the Rosenbergs’ and Sobell’s right to due process.

Most notably, in January 1953, Pauling released a statement describing a letter that he had written to President Harry Truman. Pauling’s letter focused on the President’s right to exercise executive clemency in commuting the Rosenbergs’ death sentences. Pauling believed the death sentence to be unjustifiably severe and suggested that Truman would later regret having not acted if the sentence was ultimately exacted.

Pauling also felt, as did many others, that the sentences relied too heavily on the testimony of David and Ruth Greenglass, who themselves faced comparatively light punishments (or none at all) though they had confessed to committing acts of espionage. Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, on the other hand, maintained their innocence and had received the harshest penalty possible.

After the executions of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were carried out, Pauling remained a high profile advocate of legal reconsideration of Morton Sobell’s sentence, and he continued to support the work of the National Rosenberg-Sobell Committee with this goal in mind. Many years later, in the 1970s, Pauling once again lent his name to the Rosenbergs’ cause, speaking out in favor of the National Committee to Reopen the Rosenberg Case.