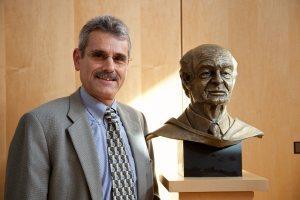

LPI Director Balz Frei, 2010.

[A history of the Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine, Part 7 of 8]

Despite Linus Pauling’s death in August 1994, prospects were finally beginning to look up for the Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine. By early 1995, finances had improved and, crucially, LPISM had decided to move from Palo Alto, California, to the campus of Oregon State University in Corvallis, Oregon.

Even though the reorganization of the Institute after Emile Zuckerkandl’s departure had shrunk its staff from 75 to 50, it was still determined that LPISM was too big to move to Oregon in its then-current size. For one, many of its development obligations would no longer need to be assumed by Institute staffers, as the OSU Foundation had agreed to lead fundraising efforts, and other staffing redundancies were quickly becoming apparent.

CEO Steve Lawson began to meet regularly with OSU’s Dean of Research, Dick Scanlan, the two carefully studying their staff lists, deciding who and what was most likely to succeed at OSU. Eventually it was agreed that LPISM would move to OSU with a skeleton holdover staff of five people: Steve Lawson, Conor MacEvilly (biochemist), Vadim Ivanov (cardiovascular disease researcher), Svetlana Ivanova (Ivanov’s wife and research partner), and Waheed Roomi (researcher focusing on the cytotoxic molaity of vitamin C derivatives) would come to Oregon.

LPI Staff and faculty affiliate investigators, ca. 1996. Left to right: (back row) Waheed Roomi, Barbara McVicar, Stephen Lawson, Donald Reed, George Bailey, Vadim Ivanov, Ober Tyus; (front row) Svetlana Ivanova, Rosemary Wander, Peter Cheeke, Conor MacEvilly; (not pictured) David Williams, Philip Whanger.

In preparing for the move, Lawson worked closely with Scanlan and OSU president Dr. John Byrne to hammer out the specifics of how to integrate LPISM into OSU. In 1995 Linus Pauling Jr., Lawson, and incoming OSU president Paul Risser all signed a Memorandum of Understanding that laid out how everything would be transferred to OSU, and how LPISM would be legally dissolved as a separate entity. OSU promised to provide the Institute with administrative and laboratory space on the fifth floor of Weniger Hall, which had just been renovated. The university also pledged additional funding for salary lines, and to work toward eventually housing LPISM in its own building should it someday outgrow Weniger Hall.

The big move was made in July 1996. LPISM was able to bring with it an endowment of $1.5 million, which the state of Oregon agreed to match. As they moved, the remaining staffers purged much of their material: Lawson estimated that they filled two full-sized dumpsters per week immediately before, during, and after the move.

Upon arrival, the Linus Pauling Institute was created as a separate entity from LPISM, which continued to exist as a shell company for several years afterward. LPISM needed to continue to live as many bequests had been specifically made out to LPISM, and there was the issue of standing lawsuits from Matthias Rath and another former staffer who was suing LPISM for wrongful termination. Due to these legal reasons, and despite the fact that, by 1996, it had ceased to exist on anything but paper, LPISM was not finally dissolved until the mid-2000s.

Maret Traber, one of the world’s leading experts on vitamin E.

Once settled in Corvallis, the Institute’s fortunes continued to improve. For one, the financial problems which had plagued the Institute for all of its life basically vanished. Regular influxes of donations coupled with residence at OSU saved a fortune for LPI, which no longer had to pay rent or keep a fundraising staff on its payroll.

Next, after a long and thorough search, Balz Frei was hired as director of LPI in the summer of 1997, a position that he holds to this day. The Institute spent the rest of the late 1990s setting up its research agenda and recruiting new faculty. In 1998 LPI hired Tory Hagen, Maret Traber, and Rod Dashwood, all acclaimed scientists whom Lawson described as the “research backbone of the Institute.” (presently all three hold endowed professorships) Shortly afterward David Williams was hired from within OSU as another principal investigator; he ended up holding numerous positions at LPI and was very important to its success in the following years.

In 2000 LPI launched one of its most successful projects: the Micronutrient Information Center, which has proven to be a highly popular and dynamic outreach program. The resource, which continues to expand, provides information on dietary intake and encouragement for healthy living. While it still advises vitamin C doses much higher than that recommended by the FDA, the numbers involved are far from Pauling’s recommended megadoses of the 1970s and ’80s.

The year 2001 was another big one for the Institute, in part because of their hosting the first Diet and Optimum Health Conference that winter. As part of the conference, they presented the first Linus Pauling Institute Prize for Health Research to Dr. Bruce Ames, along with a $50,000 award. In the span of a decade, the Institute had gone from being hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt to being able to award a biennial prize of $50,000 – tangible evidence of a truly remarkable turnaround. That year LPI also hired Joe Beckman, who opened up a new area of research for LPI through his focus on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease.

The ensuing decade was refreshingly free of drama – certainly so by past LPISM standards – and saw unprecedented growth. In 2002 the general expansion of LPI’s research support staff continued and in 2003 the second Diet and Optimum Health Conference was held with the signature prize going to Dr. Walter Willett of Harvard University. The third, fourth, and fifth conferences were held in 2005, 2007, and 2009 with Drs. Paul Talalay, Mark Levine, and Michael Holick winning the awards at each event. In 2011 the prize went to OSU alum Dr. Connie Weaver; this year the biennial conference is scheduled to take place in May, and another LPI Prize will be announced then.

Jane Higdon, 1958-2006.

In an otherwise near-spotless decade of growth and good news, one tragic occurrence did befall the Linus Pauling Institute. On May 31, 2006, Jane Higdon, a prolific writer, well-known researcher, creator of the Micronutrient Information Center, and six-year veteran of LPI, was hit and killed by a logging truck while bicycling near her home in Eugene. In her honor, the Jane Higdon Foundation was established, the trucking company involved in the accident donated $1 million to bicycle safety programs, and LPI set up the Jane V. Higdon Memorial Fund. The Higdon Foundation’s goal is to create “scholarships and grants to encourage and empower girls and young women to pursue healthy and active lifestyles and academic excellence” and also to promote bicycle safety in Oregon’s Lane County. The Memorial Fund is largely dedicated to supporting the Micronutrient Information Center.

Buoyed by the success of its past outreach efforts, LPI decided to expand its education programs to include young people as well, launching the Healthy Youth Program in 2009. The Program is aimed at elementary- and middle school-age students, and promotes healthy lifestyles and nutrition.

At the same time, LPI responded to the “Physicians’ Health Study II on Vitamin C and E and the Risk for Heart Disease and Cancer.” Published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the study claimed that vitamins C and E were useless in treating cardiovascular disease. LPI retorted that the research directly contradicted numerous other contemporary studies, that it failed to accurately measure vitamins in the bloodstream, and that a ten-year study isn’t adequate time to gauge the effect of vitamins on cardiovascular disease. LPI’s public response was emblematic of its participation in public debate; presently the Institute is looked upon as a respected and valuable contributor to many conversations concerning, as Linus Pauling would have put it, “how to live longer and feel better.”

For the first time in its existence, things were going very smoothly for LPI. As the first decade of the new millennium came to a close, the future looked even brighter, a welcome change from the past. Exciting news was not long at hand.