[Part 2 of 2]

By the end of the 1950s, Roger Hayward had retired from his professional work as an architect at the same time that his career as an illustrator was reaching its peak. And with this came a new measure of security: having worked chiefly as a freelancer in the past, Hayward signed a contract in the early 1960s that helped to solidify his position as a technical artist.

The contract that Hayward signed was with W.H. Freeman & Company, a San Francisco-based publishing house that rose out of relative obscurity primarily by publishing Linus Pauling’s hugely popular textbook, General Chemistry. First released commercially in 1948 (with illustrations by Roger Hayward), General Chemistry went through two more stateside editions, the last appearing in 1970.

Such was the pedagogical import of General Chemistry that it was translated into at least eleven languages, including Gujarati, Hebrew, Swedish and Romanian. Indeed, for several years Pauling made more money off of royalties from his textbook than he did from his Caltech salary. The impact of the book was similarly lucrative for the publishing house and its success cemented a long and close connection between the Freeman firm and Pauling.

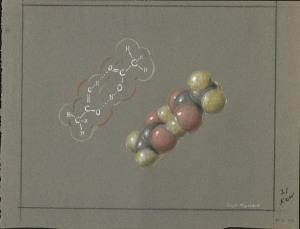

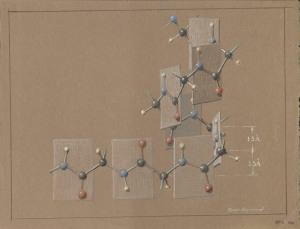

The Double Molecules of Acetic Acid. Pastel drawing by Roger Hayward. As with all of the pastels used as illustrations with this blog post, the Acetic Acid pastel shown here was not the final version published in “The Architecture of Molecules.”

For many years W.H. Freeman & Co. had also collaborated with Scientific American, publishing a selection of the magazine’s articles as offprints. Roger Hayward often found himself in the middle of this collaboration as he frequently illustrated publications for both companies.

The partnership between the two organizations proved so fruitful that, in 1964, they decided to merge, the hope being that W.H. Freeman might grow into the nation’s leading publisher of scientific texts. The joining of these two companies that he knew so well was a positive turn of events for Hayward, in part because it led to the publication of what would become his most acclaimed work, The Architecture of Molecules. A beautiful and innovative book co-authored with Linus Pauling, The Architecture of Molecules ultimately sold over 15,000 copies and featured some of Hayward’s best-known scientific illustrations.

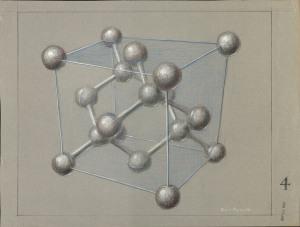

The Structure of Diamond.

In his papers, Hayward’s first mention of the book appears in a letter written in March 1964 to his long-time friend and colleague John Strong, then living in Baltimore, Maryland. In it, Hayward mentions in passing

I have just signed up to illustrate a Molecular Architecture book with Linus. The Freeman & Co. are to publish and all the figures are to be in color. I expect something like 75 figures some of which I have already done.

The idea behind the new book was to use illustrations to attract audiences from all backgrounds to an informative work on structural chemistry. The volume also represented one of W.H. Freeman’s first attempts to step away from strictly academic subjects in favor of publishing a scientific work marketed to a non-academic demographic.

Though not a technical monograph, The Architecture of Molecules was scientifically exacting in its own way. The book features Hayward’s colorful pastel conceptualizations of molecules and basic chemical bonds, and presents them side-by-side with Pauling’s concise but informative explanations of what the reader is looking at. From the first, the publication was very much a joint Hayward-Pauling project and Pauling, as with his publisher, saw the book as a tool to broaden the public’s understanding of chemistry in “an atomic age.”

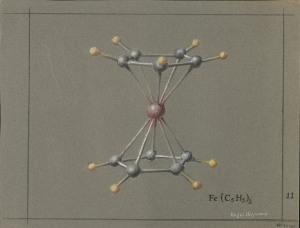

The Ferrocene Molecule.

It stood to reason then that work on the book was divided, with each author showing off some of their best qualities in their respective contributions. Hayward, of course, made it his duty to illustrate molecules with the utmost geometric and proportional accuracy. Likewise, Pauling provided pithy descriptions of the molecules and bonds being depicted, and did so in the inimitable style that characterized so much of his writing. Witness, for example, Pauling’s discussion of Left-Handed and Right-Handed Molecules of Alanine:

There are two kinds of alanine molecules, which differ in the arrangement of the four groups around the central carbon atom. These molecules are mirror images of one another. The molecules of one kind are called D-alanine (D for Latin dextro, right), and those of the other kind L-alanine (L for Latin laevo, left). Only L-alanine occurs in living organisms as part of the structure of protein molecules.

Other amino acids, with the exception of glycine, also may exist both as D molecules and as L molecules, and in every case it is the L molecule that is involved in the protein molecules of living organisms. Some of the D-amino acids cannot serve as nutrients, and may be harmful to life.

In Through the Looking Glass Alice said, ‘Perhaps looking-glass milk isn’t good to drink.’ When this book was written, in 1871, nobody knew that protein molecules are built of the left-handed amino acids; but Alice was justified in raising the question. The answer is that looking-glass milk is not good to drink.

Folding the Polypeptide Chain.

“My major asset in my work,” Hayward once wrote,” is an interest in and skill in three-dimensional thinking. This is coupled with a great interest in how things are put together both as an arrangement in space and in the physical sense.” In this sense, The Architecture of Molecules nicely summarizes Hayward’s true passions.

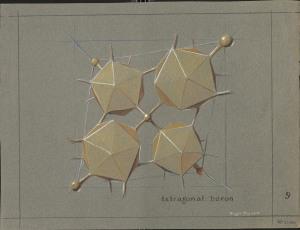

And in Pauling, Hayward was teamed with a more than capable second set of eyes. Most notably, Pauling’s familiarity with the time period’s cutting edge research enabled him to make suggestions for updates to some of the illustrations that Hayward already had in hand. His urgings also resulted in the inclusion of crystal structures as a more significant part of the book than was originally envisioned.

At various points throughout its 120 pages, The Architecture of Molecules also stresses the importance of understanding how the basic principles of chemistry are part of every-day life. Structures like the heme molecule and the alpha helix are therefore presented as exciting examples of newly discovered molecular structures that play a central role in the lives of all beings.

The Tetragonal Boron Crystal.

After hitting the market late in 1964, The Architecture of Molecules received generally positive reviews, though some critics took pains to point out that the book represented “Pauling’s view of the universe at the molecular level.” At the time, knowledge of the structure of atoms and molecules remained mostly based in theory – microscopes of the era still could not see on the molecular level and x-ray diffraction remained a technique that required years of practice to master – and Pauling’s ideas on chemical bonds, while hugely influential, were not universally accepted.

The increased use of x-ray diffraction within the discipline, however, further pressed the need for a compilation of illustrated molecules to be used as a tool for teaching chemistry. Pauling was also a firm believer that students would learn better if they understood the physical characteristics of chemical compounds. Based as they were in the latest findings, the illustrations featured in Pauling and Hayward’s book represented a contemporary vision of molecular structure.

The Architecture of Molecules clearly fit a niche and it sold relatively well – over 12,000 copies purchased in the U.S. and another 3,500 overseas. Part of the book’s foreign gross came by way of two translations; a Japanese version appeared in 1967 and a German edition was released two years later.

Today The Architecture of Molecules certainly stands as Roger Hayward’s highest profile publication, and arguably his most important. Hayward was a huge talent, remarkable in his ability to combine a desire for scientific development with a strong artistic aesthetic. Never formally trained as a scientist, Hayward’s work as an illustrator and as a colleague of some of the top researchers of his time earned for him a permanent place in the history of science communication and education.