It is remarkable how Deleuze has forged the impassioned ramblings of Francis Bacon into a deep and cohesive philosophy. I find there is nothing particularly incoherent about Bacon’s convictions about painting, only that in themselves they are almost banal, and Deleuze has elevated them to a surprisingly intellectual status. Nevertheless, Bacon’s mundane observations, perhaps cryptic to a non-painter, are at least refreshingly down-to-earth and as such offer fertile soil for the creator of concepts—the philosopher. The meta-reading of these interviews, then, is that a philosopher may not need to dig so deep, but to simply meditate on the relations between things, and his own philosophy will emerge organically, firmly rooted in ordinary experience (Deleuze and Guattari, 1994: 90).

For any painter will laugh upon reading Bacon’s solemn answer to David Sylvester’s (1975: 18) inquiry about his decision to stop a painting: ‘the canvas becomes completely clogged, and there’s too much paint on it—just a technical thing, too much paint, and one just can’t go on.’ Is this a technical thing? Indeed, sometimes one piles on so much paint that the thing gets out of control, edges mash that should not, would-be layers collapse into each other; it is better to let the thing dry than to go on today—a thoroughly non-philosophical answer, disappointing to thinkers, entirely obvious to painters, and thus despite its lack of claim to being an active ‘technique,’ possibly something that can indeed be cast into the fearful ‘technical’ category.

In this sense, ‘technical things’ are all those unspeakable, messy processes that happen in secret behind the closed studio door, generally barred from aesthetic discussions that would rather poke at the dry, finished result (preferably from behind glass, and with a very long stick). They could even include preliminary decisions, perhaps in the art shop, about the size and shape of brushes to buy, whether to select natural or synthetic fibres, preferences for the ‘springiness’ of the bristles (tested by an expert hand, but verbally inexplicable). They might encompass having to cope with stiff, old brushes out of sheer poverty. They could include unforeseeable and uncontrollable lighting conditions afforded by uncooperative weather, shifting the hue of the work without the conscious knowledge of the painter.

In any case, before we even come to talk about intentional use of color or tone, there are many inputs and decisions that steer the course of a painting and directly influence what we like to think of as the aesthetic qualities of the work. Deleuze (2003: 86; 93) would include them in his ‘givens,’ the ‘clichés’ that pollute the canvas before a painting is started. But in Bacon’s (1975: 82) rugged simplicity, he speculates that he is ‘probably much more concerned with the aesthetic qualities of a work’—the technical, as opposed to the psychological, aspects of his painted screams. This is a particularly nice observation. Many artists simply care more for the visual qualities of their work than for conveying something to some audience. These visual qualities, coaxed into existence by a perceptive painter, may finally move some unsuspecting viewer and stir all sorts of lofty thoughts in his contemplative mind. But as the genesis of these thoughts, possibly inextricable from these thoughts, might not these mere ‘technical things’ themselves comprise a very important part of aesthetics? Are they not precisely what we want to talk about?

For a humble painter is one of the few willing to simply confront a work on its own physical terms. She surveys the array of technical choices and chances, the resulting relationships between elements, and considers their degree of success. She is willing to consider what the paint itself may say, not merely what it may allude to or denote or represent. Bacon (in Sylvester, 1975: 61) shrewdly notes ‘that most people enter a painting by the theory that has been formed around it and not by what it is.’ They prefer to approach a painting through an indirect, non-visual route. They could shut their eyes and listen to information instead.

It is in abstract painting that people might find the courage to let mere colours and shapes touch them, rather than to search for ideas outside of the painting. What is clear to non-abstract painters is that the sensory force of colours and shapes is available and able to be manipulated even in very naturalistic painting. Abstract painting ‘can convey very watered-down lyrical feelings,’ scoffs Bacon (in Sylvester, 1975: 60), ‘because I think any shapes can.’ And timid observers can project themselves and most anything they like onto the distilled forms of abstract painting. The point is so plain it is hardly raised among painters. It is simply part of our job to actively design an image, to exert control over it, even if we hide our tracks and make it feel inevitable.

And so Bacon (in Sylvester, 1975: 58) repeatedly explains that he is seeking just such direct contact between the painting and the nervous system—the immediate impact of colours and shapes (and every other technical thing), without the mediation of the brain. His phrasing seems oblique and troubling to Sylvester and deep and insightful to Deleuze. One senses that Bacon has finally thought of some words that best approximate this very ordinary painterly experience that might finally get across to these wordy people, that they swirl around in his head until they take the form of some mystical mantra. His words are exceptionally nice, and give the painter a little jolt: because she, too, knows that the best painting works without intellectualisation, that the body itself responds to an exquisite harmony of colours or a pulsing, rhythmic line. Good painting feels immediate, it does not require deciphering, though it may entice one to look longer, to dwell upon the picture and soak up its sensations.

Bacon (in Sylvester, 1975: 120) is firmly convinced that this immediacy, this freshness, must come about through chance. That the coveted deftness of touch, effortless finish, virtuoso resolution, can only be captured unawares, never intentionally. Though he seeks order in painting, he fears that it will look laboured, and prefers that the work look as though ‘it hasn’t been interfered with’ (Bacon, in Sylvester, 1975: 120). This exposes the naïveté of a painter who does not know how to set himself technical problems and to set about solving them. For while he is right that freshness is compelling, such fluency can most certainly come about through knowledge and disciplined application. More adept painters than Bacon have used their knowledge to produce lucid and nervous-system-gripping works, still driven by their own personal sensibilities.

And this is another nice observation of Bacon’s, painfully unnoticed by too many painters. The inventiveness of an artist lies not in the originality of her techniques, but in the pursuit and cultivation of her own sensibility. ‘I’ve never felt it at all necessary to try and create an absolutely specialised technique,’ Bacon (in Sylvester, 1975: 107) declares, and one must not reflect long to call to mind the futile manner in which artists—now more than ever—try to distinguish themselves, dreaming up novelties external to themselves: watercolours fabricated out of dissected felt-tip pens, drawing in crayon onto torn pieces of cloth, tearing old posters from the street, growing seeds inside a pyramid of fluorescent lights. The novelty of our technique may win us some attention, but it will never remedy a weak sensibility.

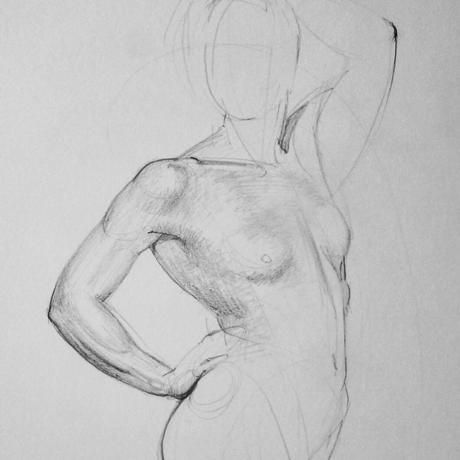

Sensibility, of course, being a well-chosen word: it draws our attention to an artist’s sensory intersection with the world. The point warrants attention, because I think a non-painter is content to let most of the visual world wash over him, hardly taking it in. A non-painter uses his senses for gathering relevant information; a painter stops to drink in the pink and blue ferment of the sky and shouts, ‘Look at the clouds!’ while the helpful and oblivious non-painter replies, ‘Don’t worry, the storm is moving away from us.’ A painter, one worthy of the name, is genuinely attentive to visual stimuli, is acutely perceptive, is besotted with sight. She hardly has to invent visually interesting things—she is overcome by the sensory cornucopia of existence and is struggling to survive such abundance by her feeble attempt to instate order through her brush. A painter’s sensibility will most certainly emerge if she works with technique rather than against it, as she comes nearer to her sensory reality as her facility with her techniques grows. Perhaps a furious linear energy drives through the human form; perhaps muscles swell according to certain rhythms. Though she ‘may use what’s called the techniques that have been handed down,’ like Bacon (in Sylvester, 1975: 107), she may use them to create powerful work that has never yet been made, declaring with Bacon: ‘my sensibility is radically different.’

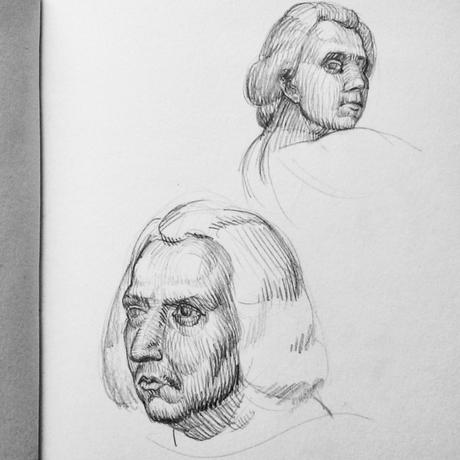

Copy after Steinl, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

I am not defending the type of fluency that produces indistinguishably polished works. Rather, the painter should use her hard-won ability to investigate, to explore, to forge connections that others might not see. One way to stay alert is to make things harder for oneself. Bacon (in Sylvester, 1975: 91) explains: ‘Half my painting activity is disrupting what I can do with ease.’ His insight has always been made by the kind of painters who prefer to test their abilities and extend them more than they care to show off. David Paulson is the kind of painter who works with stubs of pencils, works with his left hand, intercepting his habits with stumbling blocks that force him to work hard to regain control, or, more accurately, to gain a different kind of control.

Under this kind of self-sabotaging lies a desire to find and apprehend new problems. Bacon (in Sylvester, 1975: 37) discusses the difference between working from photographs of paintings, such as the Velazquez popes he had about his studio, and working from photographs of people, explaining that the paintings present problems that are already solved. An artist makes copies of old masters because there is something to be learned by tracing the solutions of someone more advanced. She recognises the problem she would like to confront, and follows the thought processes of another by mimicking their actions. ‘The problem that you’re setting up, of course,’ says Bacon (in Sylvester, 1975: 37) ‘is another problem.’ It is when we apprehend the physical world through our own senses that we discover problems demanding fresh solutions. And when we find ourselves turning again and again to the same reliable solutions, we must interrupt the process manually, thwarting our usual responses such that we not only respond in a new way, but set up the problem in entirely different terms.

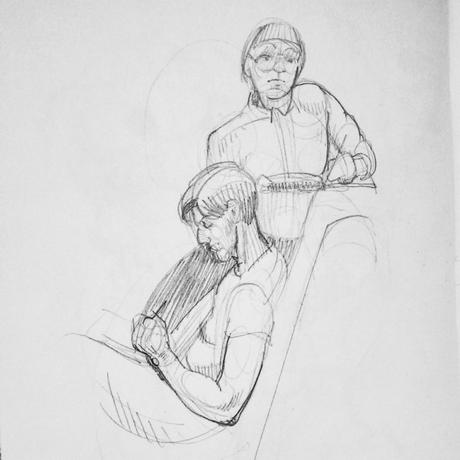

And Bacon rightly recognises that few are sympathetic to this personal struggle. Each new painting, each portrait sitting, offers the opportunity to probe some quietly festering problem. It demands untested approaches, not guaranteed to succeed. The sitter expects an exquisite rendering of their face; the painter relishes the opportunity to wrestle with bold new ideas. The sitter grows apprehensive, gradually becomes alarmed. ‘In what sense do you conceive it,’ what you are doing to their face, ‘as an injury?’ asks the moderate Sylvester (1975: 41). The painter can hear Bacon scowl. ‘Because people believe—simple people at least—that the distortions are an injury to them’ (in Sylvester, 1975: 41). And distortions they must be, in the tussle with the problem, in the trial of new responses. Because of this, it can become unpleasant to work with a model. We must pretend that we are immortalising their appearance, to placate their doubts; we would rather shut them out entirely, except for the bundle of gripping visual problems they represent, and ‘practice the injury in private by which [we] think [we] can record the fact of them more clearly’ (Bacon, in Sylvester, 1975: 41). Sylvester (1975: 43) tries to extract something psychological out of the discomfort: Perhaps ‘what you are making may be both a caress and an assault?’ Bacon assures him he need not make so much of the matter. It is hardly a deep psychological tension, but simply that ‘they inhibit me’ (Bacon, in Sylvester, 1975: 41).

Copies after Titian, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

The thrust of Bacon’s discussion of painting, however, might be reduced to the omnipresent frustration that paint does what it wants. When he trusts everything to chance, he is giving himself over to the fact that paint is disobedient, that the most controlled stroke defies control. He almost boasts that ‘in my case all painting … is accidental,’ because ‘it transforms itself by the actual paint’ (Bacon, in Sylvester, 1975: 16). All of Bacon’s (in Sylvester, 1975: 97) language about paint—‘such a fluid and curious medium’—suggests the near superstitious reverence of paint familiar to the painter. Paint seems to have agency—perhaps painters secretly believe it. ‘I don’t in fact know very often what the paint will do,’ admits Bacon (in Sylvester, 1975: 16; 54), or ‘how [these marks] will behave,’ as though the paint is another active participant, responding to his choice of a large brush with an unexpected manoeuver. Paint is so deliciously malleable but it does not bend to our every intention; paint is ever the volatile element in a painting (Bacon, in Sylvester, 1975: 93). He fears to invite a story into the painting, in case it should ‘talk louder than the paint’—which, we might presume, is talking too, if softly (Bacon, in Sylvester, 1975: 22). Perhaps it sounds mystical to speak in hushed tones about this silent back-and-forth between painter and paint, to attribute the uncontrollable features of paint to its own will. But Bacon describes something very real to the most experienced of painters, something which lies at the heart of the attractiveness of painting. Painting will always be a challenging and thus deeply demanding and rewarding medium, because of paint.

‘I don’t think that generally people really understand how mysterious, in a way, the actual manipulation of oil paint is,’ Bacon (in Sylvester, 1975: 121) comments, and perhaps here he gives the most profound insight of all. To an outsider, a painter must simply master those tricky technical things, master paint, and put this mastery to good use. But the pleasure and the satisfaction of painting derive from paint’s continual defiance of the painter’s every attempt to constrain it, to impose order, to systematise, to achieve fluency. It is paint itself that is profoundly and infinitely interesting—those mere technical things that scamper at the edges of aesthetics. The non-painter need not dig so deep for profound insights, for they are not so intellectual as might be supposed.

Deleuze, Gilles. 2003. Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation. Trans. Daniel W. Smith. 1 edition. Continuum: London.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Guattari, Félix. 1994 [1991]. What is Philosophy? Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell. Columbia: New York.

Sylvester, David. 1975. Francis Bacon, Interviewed by David Sylvester. Pantheon: New York.