Today, I'd like to share with you a statement from Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests (SNAP), which appeared a few days ago at Marci Hamilton's blog, Hamilton and Griffin on Rights. It's an appeal for religious leaders to place a year's moratorium on talk about forgiveness in clergy abuse cases.

As SNAP notes, discussions about forgiveness, pro and con, have been very much in the U.S. public mind lately, with the horrific shootings in Charleston followed by statements of forgiveness that surviving family members of the victims then made to the shooter, Dylann Roof. We've discussed some of those pro and con statements here at Bilgrimage. There has been an extensive discussion at various blog sites, in which some commenters have noted the centrality of the command to forgive always and everywhere in the Christian tradition and how excellently those family members in Charleston modeled it, and in which others have noted the way in which ruling elites and privileged interest groups can co-opt the language of forgiveness and use it as a tool to suppress the kind of righteous anger that fuels much-needed social change.

Here's SNAP's take on how the concept of forgiveness is often used by church leaders in abuse cases:

But it's [i.e., forgiveness is] also sometimes a distraction from more pressing business. It's sometimes exploited by self-serving officials who want to "turn the page" and "move on" from still-simmering scandals.

And it's sometimes almost force-fed to victims, church staff and church members who should actually be focusing on proven prevention steps first. . . .

For years, clergy have drilled into millions the moral imperative of forgiveness. Therapists have taught millions the practical benefits of forgiveness. Friends and family, from first-hand experience, have told millions of the value of forgiveness.

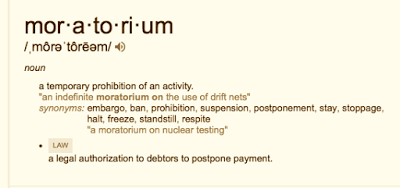

So if – out of caution – church officials and members take a moratorium on talking forgiveness, only in cases of clergy sexual abuse and misdeeds, it’s not as if all of us will forget how good and important this precept is.

And we might use that space, time and energy to put "first things first," by practicing an even more pressing precept – prevention.

As SNAP notes, rather than sponsoring the "healing services" that have now become conventional when allegations of abuse of minors by clergy are made public, churches might sponsor "outreach services," instead, in which they seek to educate folks about clerical sexual abuse of minors and invite others who have knowledge of such abuse to report it to the proper authorities. Instead of sending to parishioners the letters that have now become conventional in these cases, which beg for forgiveness for errant clergy, churches might send out letters providing practical advice about how to reach out to people who have experienced this type of abuse.

A mature moral life, whether one informed by norms taken from faith traditions and sacred books or one that eschews such norms, always requires us to balance. Mature moral thinking calls on us to live in tension, as we deal with moral imperatives that do not always neatly cohere together. It requires us to take into account norms that may not always point in precisely the same direction.

The Christian tradition stresses the obligation to forgive always and everywhere, and to recognize that forgiveness for our own shortcomings is hinged on our willingness to forgive others. In abuse cases, that obligation has to be weighed, however, against norms that call on us to protect the weak and to do everything in our power to combat the evils that we have the ability to combat in our daily lives — to address forthrightly cases of clerical sexual abuse of minors by speaking the truth about these cases, keeping more minors from being in harm's way, and offering robust, meaningful support to those who have been harmed.

The premature application — the conventional thoughtless application — of the concept of forgiveness in these situations can do further violence to those who have been harmed by clerical sexual predators. As Australian Catholic bishop Geoffrey Robinson observes in his ground-breaking work Confronting Power and Sex in the Catholic Church: Reclaiming the Spirit of Jesus (Dublin: Columba, 2007), paths to healing differ from individual to individual (pp. 219f), and no one should dictate how the healing process should unfold in the case of another person wounded by abuse, or tell that person not to feel pain and anger or to speak of these emotions.

As Robinson writes,

To think of the abuse and not feel angry is simply not an option. When memory of sexual abuse comes to mind, the anger that is spontaneously felt is in fact positively good and contributes to a sense of meaning because it is part of the loving of oneself. The anger is a defensive reaction, an affirmation of oneself and one’s own dignity, an instinctive statement that what happened was wrong, that I (the victim) am worth more than that (p. 221).

There is, in fact, Robinson insists, such a thing as forgiveness given too early (p. 222), which masks the need for healing inside a person not ready to offer forgiveness. It violates the integrity of such a person to insist that she forgive now, and it thwarts her process of reaching for psychic healing.

Robinson concludes, vis-a-vis the concept of forgiveness and how it should be used in Christian communities dealing with abuse cases:

There is another forgiveness that is essential. Communities must forgive, in the literal sense of "give themselves for", victims who have disturbed their comfort and meaning-making by speaking out about their abuse. Within the Catholic Church I must accept that, if no victims had come forward, nothing would have changed. We must learn to be positively grateful to victims for disturbing us. If we feel that we have lost some meaning, it was a false meaning, and their revelation has opened the way to a fuller and more rewarding meaning (p. 225).

I think Geoffrey Robinson is absolutely correct in these observations, as I think SNAP is, too, in calling for a moratorium on the easy, bandaid-on-the-cancer talk about forgiveness often bandied about my Christian communities today faced with stories of sexual abuse of minors by clergy. Faced with actual human beings, wounded ones, who are living with the effects of such abuse . . . .