The title of the chapter in her book “Surviving the slaughter” is Descent into Hell. Marie Beatrice Umutesi tells in her testimony how she experienced the fatidic day when the former Rwandan president Juvenal Habyarimana was assassinated. 1994 is part of that era of African history that started with the last years of the Cold War and which is far from ending. In the course of the tragic events that came one after another in different countries across Africa, Africans have not been valued as the rest of human beings on the planet. Their slaughter that enfolded then is still continuing because global powers and their local agents full of their egos have their eyes of the continent’s mineral resources and other riches. They will carry on with all imaginable stratagems, including the deceptive use of UN peacekeepers like MONUSCO in the Democratic Republic of Congo, until concerned Africans stand up and defend their right to life.

The title of the chapter in her book “Surviving the slaughter” is Descent into Hell. Marie Beatrice Umutesi tells in her testimony how she experienced the fatidic day when the former Rwandan president Juvenal Habyarimana was assassinated. 1994 is part of that era of African history that started with the last years of the Cold War and which is far from ending. In the course of the tragic events that came one after another in different countries across Africa, Africans have not been valued as the rest of human beings on the planet. Their slaughter that enfolded then is still continuing because global powers and their local agents full of their egos have their eyes of the continent’s mineral resources and other riches. They will carry on with all imaginable stratagems, including the deceptive use of UN peacekeepers like MONUSCO in the Democratic Republic of Congo, until concerned Africans stand up and defend their right to life.

I spent the tragic evening of April 6, 1994, in the Hotel Meridien in Kigali with my roommate Goretti and a friend of hers, an officer from Ghana. He was a member of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR), the force that had been created by the UN to implement the peace agreements that had been signed by the Rwandan government and the rebels. Goretti and I arrived home about eight o’clock. When we were a few yards away from the house, we heard a deafening noise. We didn’t pay too much attention to it, since we thought it might be a grenade that had just exploded somewhere in the nearby area of Kabeza. During the last few months, grenades exploding in cafes and houses as soon as night fell had become part of our normal life. As long as you weren’t the target yourself, you didn’t worry about it too much. Around midnight, the policeman came to wake me and tell me about Habyarimana assassination. He was returning from a meeting of the heads of state of the countries of the Great Lakes Region in Tanzania, accompanied by President Cyprien Ntaryamira of Burundi, the head of FAR (Forces Armees Rwandaises), and other important members of his regime. The presidential airplane had been shot down as it was landing at the international airport at Kanombe. Lightning couldn’t have struck me harder. With President Habyarimana dead, what would become of us? There was bound to be war. The reprisals would be horrific. Ethnic disturbances, which were sure to follow, would be the excuse for the RPF to resume hostilities. With the political situation in the country so degraded and the practically nonexistent government, the final confrontation, predicted by all the different political factions, was guaranteed. The only force that would still be able to pull us out of the hornet’s nest was UNAMIR. Nevertheless, their passivity during the bloody riots following Bucyana Martin’s assassination did not leave much room for hope of any intervention on their part.

After the policeman left, I woke the entire family to tell them the bad news. At that there were about fifteen of us sharing the house: my mother, many of her grandchildren, my unmarried younger sisters, and Goretti and her son. Our family also included two young servants. I was too frightened to stay alone in my room because I expected that at any moment a grenade would shatter the windows. I spread out a mattress in the hall, next to my mother’s and sisters’ rooms, where I felt safer. All night long I couldn’t close my eyes. I was tormented by the thought that on the next day I might not be alive and that my entire family might be exterminated. I didn’t spend much time wondering about the identity of those who had just condemned thousands of Rwandans to death by assassinating President Habyarimana. As far as I could see, the RPF was behind the assassination. The rebels had many reasons to wish Habyarimana dead. For the rebellion and its allies, the only way to gain power was behind the assassination. The Arusha Accords had brought him back to oversee the two-year transition period, and there was a good chance that he would be reelected at the end of that time. Habyarimana still had staunch allies, such as France, which came to his rescue every time that the rebel attacks threatened Kigali. As long as he was alive, military victory by the rebels remained in question. The principal reason that the Tutsi refugees had taken up arms was to gain power. Now, the Arusha Accords only gave them part of what they wanted. With the elections, Tutsi representation in the political institutions of the country would be marginal, and it would be difficult for the rebels to return to square one after having made so many sacrifices. Like most Rwandans, the rebels expected widespread ethnic riots if President Habyarimana were killed. This was predictable, because the assassination of less important Hutu leaders during the preceding month had led to bloody riots in which Tutsi had been killed and might have served as an excuse for the RPF to renew hostilities. They were prepared. During the entire ceasefire, they had never stopped recruiting. The majority of Tutsi students had left school and joined the rebellion in response to promises of money or the chance to enroll in foreign military academies once the war was over. Still, it was hard for me to accept that the rebels did this knowing that the assassination would lead to many thousands of Tutsi deaths. I refused to believe that they had made the cold-blooded decision to sacrifice hundreds of thousands of Tutsi living in Rwanda who, during the four years of the war, had kept them going by sending their sons to the front, while carrying out a successful political campaign in the interior.

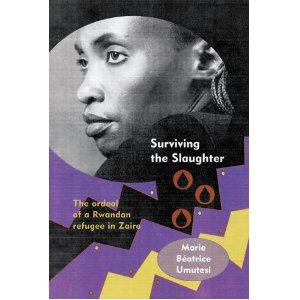

Extract from Surviving the Slaughter, Chapter 3 Descent into Hell, The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004, pages 45 – 47. Originally published in France as Fuir ou Mourir au Zaire, L’Harmattan, 2000.