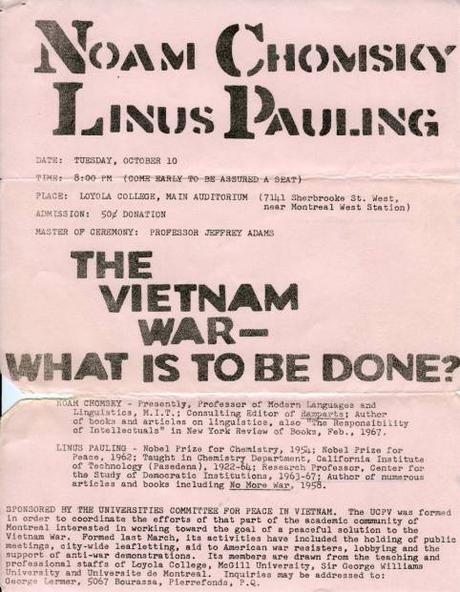

Flyer for a joint Chomsky-Pauling presentation, Montreal, 1967

[Pauling and the Vietnam War, part 6 of 7]

As the 1960s moved forward, Linus Pauling’s interest in contributing to an academic circle that resolutely rejected the Vietnam War continued to strengthen. A participant in several past petitions, Pauling co-authored another such document in June 1967, a “Scientists’ Appeal for Vietnam,” signed by a collection of scientific all stars including Nobel laureates Pauling, Lord John Boyd Orr, Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, Alfred Kastler, André Michel Lwoff, C.F. Powell, Bertrand Russell, R.L.M. Synge, and Albert Szent-Györgyi. Additional signatories included Pauling’s close friend J.D. Bernal, an influential x-ray crystallographer and peace activist; neurologist and president of the Association of Scientific Workers Harry Grundfest; Soviet biochemist Alexander Oparin; and an Indian scientist and activist, S. Hussain Zaheer.

The Scientists’ Appeal decried escalating American violence in Vietnam, pointing out that U.S. aggression was being mounted in direct opposition to strong world opinion against the war. In addition to publicly denouncing American foreign policy in Southeast Asia, each of the appeal’s signatories also reaffirmed their commitment to international science by donating one day’s salary to help buy books for the University of Hanoi and to support the continued functioning of scientific laboratories in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

About a month before the appeal was released, Pauling attended a second Pacem in Terris conference, held this time in Geneva, Switzerland. Working through the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, a Santa Barbara-based international think tank where he was a fellow, Pauling helped to coordinate the convocation.

One of the more pressing agenda items on the conference planner’s wishlist was the need to highlight the Vietnamese viewpoint on the war and, if possible, to bring National Liberation Front delegates to the podium for European and American participants to see and hear. In pursuing this, the World Council of Peace acted as intermediary, handling letters between Linus Pauling and the Vietnam Peace Committee. However, citing an inability to travel due to the escalating conflict in North and South Vietnam, neither representatives from the Democratic Republic of Vietnam nor from the National Liberation Front attended the event.

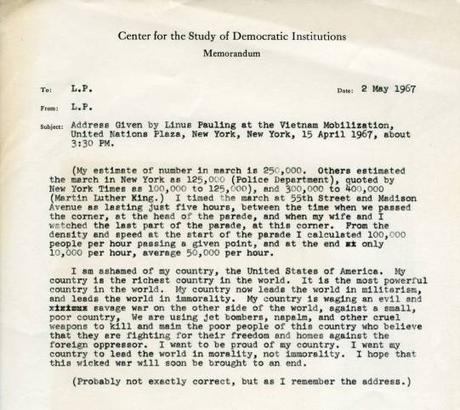

Pauling note to self, May 2, 1967

By the time that Pauling arrived in Geneva, he had established himself as a leading academic voice against the Vietnam War. Perhaps most notably, in an anti-war mobilization that took place in New York in mid-April 1967, Pauling and his wife joined a huge march to the United Nations Plaza, where Pauling then delivered an address to an audience estimated at 300,000 people. In a note to himself written a couple of weeks later, Pauling paraphrased his remarks as follows:

I am ashamed of my country, the United States of America. My country is the richest country in the world. It is the most powerful country in the world. My country now leads the world in militarism, and leads the world in immorality. My country is waging an evil and savage war on the other side of the world, against a small, poor country. We are using jet bombers, napalm, and other cruel weapons to kill and maim the poor people of this country who believe that they are fighting for their freedom and homes against the foreign oppressor. I want to be proud of my country. I want my country to lead the world in morality, not immorality. I hope that this wicked war will soon be brought to an end.

Around the same time, Pauling made another strong statement, this time to the Students for a Democratic Society:

It is the duty of every American to oppose the policy of military aggression in Southeast Asia that is being followed by our government, the government of the United States…We are now waging an immoral and inhumane war, with use of chemical defoliating, nauseating, and lachrymatory agents, phosphorous bombs, and other terrible weapons, against the people of an underdeveloped country who are fighting for freedom and self-determination. Our government has initiated an attack on North Vietnam that may grow into a nuclear catastrophe that would destroy our civilization.

Similarly, in an advertisement published in The New York Review of Books titled “A Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority,” Pauling offered his support for the “moral outrage” of young men who found that the American war in Vietnam was so offensive that they could not contribute in any way. It read, in part

Some are resisting openly and paying a heavy penalty, and some are organizing more resistance within the United States and some have sought sanctuary in other countries…We believe that each of these forms of resistance against illegitimate authority is courageous and justified.

The notice was signed by over 100 public figures, Noam Chomsky, Allen Churchill, Allen Ginsberg, Jane Fonda, Ronald Dellums, and Linus Pauling included.

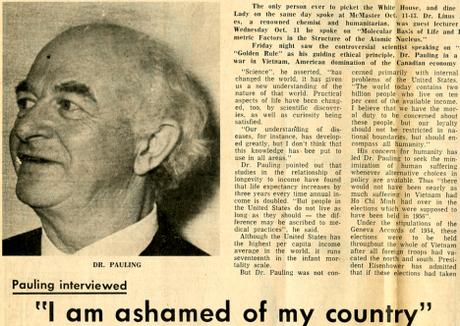

The McMaster University Silhouette, October 20, 1967

As his views about the war sharpened and his rhetoric grew equally pointed, Pauling’s anger at the present situation became increasingly palpable. Speaking on multiple occasions at universities and elsewhere, Pauling made clear that he had abandoned the search for negotiations that had marked his public stance two years prior. In its place was an increasingly polarized viewpoint that had shifted from a hoped for solution to a complex problem, to abject condemnation and disgust.

This point of view was on clear display in August 1967, at a Hiroshima Day demonstration held in Los Angeles. Speaking there in observance of the nuclear attack on Japan some twenty-two years earlier, Pauling took the opportunity to focus on Vietnam.

The crime of Hiroshima was excused by President Truman as needed to save the lives of American soldiers. This is false. It was an act of the Cold War against the Soviet Union….Friends, fellow citizens of the United States of America, my fellow Americans: We are criminals, you and I, the members of Congress, President Lyndon B. Johnson—we are all criminals….If President Johnson had to kill – shoot, burn to death – ten Vietnamese women and children every morning before breakfast, the war would soon end.

But the public did not see the true victims of the war, the war in its totality, nor the cost on both sides, and this, Pauling contended, was one of the many great lies that kept it going.

Moreover, Vietnam was only one part of a bigger picture that Pauling now begged the public to recognize. Rich nations – the United States being chief among them – had profited tremendously from the suppression of human rights campaigns, with profits from investments in poor and underdeveloped countries doubling over the past ten years.

This continuing state of affairs, Pauling argued, was enforced by the might of a United States military that now spanned the globe. Likewise, the U.S. had tactically distributed $48 billion in munitions to militant proxy groups in numerous countries over the past sixteen years.

In short, the scope of the problem was not limited to Vietnam. Rather, Pauling now felt that Vietnam was merely the most tragic and horrific example of what the United States had become in the Cold War Era: a economic and military empire willing to arm groups around the world that were beholden to American interests or, as needed, unleash its own military directly.