At last I begin to pull the threads of my life together—to pare back the things that distract me, to braid my core pursuits together into one strong cord. Each sphere of my life centres around art in some manner: I have indeed run away to Europe to be a painter; I am deeply embedded in the sketch groups we have nurtured in Vienna, even extending my involvement to teaching drawing, and I am beginning to find my way in the University of Vienna as a philosophy doctoral candidate, wrapping my brain around some aesthetic ideas that have their roots in very old Germanic thought. And, of course, I have a circle of young and agile minds around me, constantly charging my head with new and difficult ideas. I couldn’t imagine a more practically, intellectually and socially demanding and satisfying way of life.

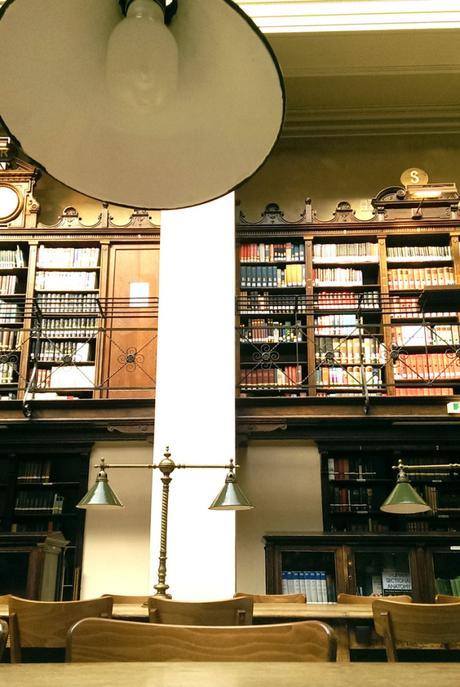

Universität Wien

When I think of these circles, through which I move so fluidly, I realise that the divide between the scholarly and the artistic can be unexpectedly deep. I see the thinkers’ mistrust of painters’ visual ideas, and I see the painters’ discomfort at others intellectualising their field. At best, the intellectuals graciously entertain thought experiments, but perhaps fail to appreciate aspects best approached by doing, if not denying them entirely. The painters, meanwhile, either quickly become intimidated, boasting loudly about a non-academic book they’ve read or bowing to any thinker who uses big words, or shunning anything that reeks of intellectualism. This disconnect seems alarming at first.

(c) Sasa

But when a painter friend, confronted with an aesthetic idea, felt the need to defend himself, it became much clearer to me. ‘Painting is breathing,’ he said simply, his open hands revealing his sense of explanatory inadequacy. Painters presume that scholarship establishes some kind of framework, a justification for painting. Painters themselves usually don’t have a rigorous theoretical conception of painting, they are simply compelled to paint. And those that seek to find one sometimes spiral into impenetrable written treatises whose ability to improve, support or defend their practical work is deeply questionable. But perhaps this burden doesn’t really exist. No painter should feel threatened by a scholar of aesthetics, or feel that their work is incomplete without theory. Painters and scholars are simply not at all aiming at the same thing.

(c) Sasa

Hermann Weyl (1968: 631), the German mathematician, physicist and philosopher, makes an illuminating distinction between Erkenntnis and Besinnung:

‘Im geistigen Leben des Menschen sondern sich deutlich voneinander ein Bereich des Handelns, der Gestaltung, der Konstruktion auf der einen Seite, dem der tätige Künstler, Wissenschaftler, Techniker, Staatsmann hingegeben ist und der im Gebiete der Wissenschaft unter der Norm der Objektivität steht—und ein Bereich der Besinnung auf der andern Seite, die in Einsichten sich vollzieht und die, als Ringen um den Sinn unseres Handelns, als die eigentliche Domäne des Philosophen anzusehen ist.’

[‘In the human mental life there is rather—clearly distinguishable from one another—a region of actions, creation, construction on one side; that which is given to the active artist, scientist, technician, statesman and that which stands in the domain of science under the norm of objectivity—and a region of reflection on the other side, that takes place in insights and that, as rings around the sense of our actions, is to be seen as the actual domain of philosophers.’]

According to Weyl (and very sensibly, I would suggest), the activities of the philosopher, while posing questions which stem from art or any other human endeavour, are of an altogether different nature than the practical activities themselves. While it orbits around the practice of art, it does not so much support it as probe it, test it, inspect it, challenge it, ponder the nature of it. Philosophy of art as Besinnung, as a contemplative reflection on what art is and what role it plays, is a very different thing from the Erkenntnis, the technical knowledge, that painters cultivate. Philosophers unearth puzzles about the nature of beauty, of sensations, of the role of art, of its ethical import. They try to make sense of the commonalities among the arts, the significance of objects, what ‘style’ could mean, what types of meaning exist in paintings and whether the painting or the painter is self-reflexive. These endlessly fascinating puzzles emerge from the nature of painting, but to be a better painter, one must concentrate on how to mix paints and how to stick them to a surface.

The painter, by contrast, busies herself with visual problems: problems of space and depth, of volume and design, of edges and atmosphere, of the translation of ideas into a physical substance. She grapples with the aesthetic experiences themselves: the intense sensations and emotions and how to record them, how to ignite them in others, how to use a humble physical medium to stir something less rational than the intellect.

These aims, however divorced, need not be antagonistic. Philosophy need not be inaccessible: aesthetic ideas can be expressed clearly and generously. And perhaps philosophical insights, while not justifying painting, or dictating the way in which it should go, can open new avenues for thoughtful painters, or help clarify the nebulous thoughts already hovering in their minds. I only hope that as a painter myself, my philosophical investigations will remain grounded and intelligible because of my honest contact with painting itself. But I seek not to justifying painting—only to obsess over it in another manner.

Weyl, Hermann. 1968. ‘Erkenntnis Und Besinnung (Ein Lebensrückblick)’. In Gesmmelte Abhandlungen IV, 631–49. Berlin: Springer.