As this 2008 book’s title suggests, Sarah Vowell is a funny writer. Yet also a serious one. She writes serious books in a funny way. This one is actually a substantive chronicle of, and rumination upon, the Puritans who founded Boston. She quotes liberally from original sources. Interspersed with wisecracks.

As this 2008 book’s title suggests, Sarah Vowell is a funny writer. Yet also a serious one. She writes serious books in a funny way. This one is actually a substantive chronicle of, and rumination upon, the Puritans who founded Boston. She quotes liberally from original sources. Interspersed with wisecracks.

Also prominent is Roger Williams. Now, I have a thing for Roger Williams. I happened to live for 11 years with his great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grand-daughter.* So I almost feel kin to him, or as much as a Jewish kid from Queens could.

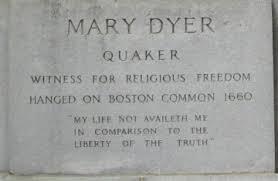

I’m always struck by the certitude such people felt about their faith. Didn’t they realize millions of others had entirely different beliefs? Indeed, they spent a lot of effort massacring them. Yet never seemed to ponder the impossibility of knowing who’s right. (Most believers still don’t.)

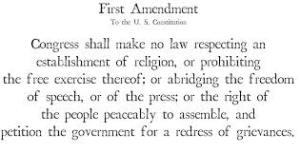

Roger Williams was a titan of certitude. His inability to soft-peddle his convictions – he considered his neighbors insufficiently Puritan – got him kicked out of the colony. Thus was Rhode Island founded.

One criticism of this book. Winthrop was famous for his “city on a hill” sermon, so often invoked by Ronald Reagan. Vowell takes this as a pretext for a vicious diatribe against Reagan (and drags in Bush 43 as well). She quotes liberally from Mario Cuomo’s speech mocking Reagan because in America’s “shining city on a hill” there are people suffering.

But to some people nowadays everything is political, and they are so imbued with (what seems to them) the righteousness of their views, they cannot ever desist from being in your face with them. They’re almost like . . . well, the Puritans.

* Not really special. A typical person 11 generations back would have a lot of modern descendants. And conversely, everyone today has a lot of ancestors back that far – 2,048 to be exact. The number doubles with each generation going backward; so after a few dozen your roster of ancestors would exceed the entire human population. How can that be? Well, your family tree is tangled with everyone else’s. We are all related.