“Playing” for Time

Black Orpheus (filmsquish.com)

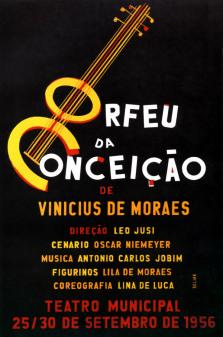

The most striking thing about the episodes in Orfeu da Conceição is how little they have in common with Marcel Camus’ rosy-eyed vistas of Rio: no streetcar-conducting lead; no enchanting ferryboat ride; no colorful costume pageant, as such; no return and parting of Orfeu’s lost love; and no voodoo mumbo-jumbo, either, although Dama Negra does get to perform a bit of macumba during portions of the play’s opening act. Oh, and Cerberus, the guardian canine of the realm, puts in a guest howl at the second act dance-club sequence.

Otherwise, in Camus’ grandiose treatment of Carnival, Orfeu is not torn to shreds by an angry mob of whores but instead falls off a steep cliff holding on to his expired love after being conked on the head with a rock. If Vinicius de Moraes hadn’t left the theater by that point, he most assuredly would have done so here, so dissimilar was his play from the movie — the undeniable irony of which never fails to impress, in that there would be no staged play at all without the insistence of the French for a screen treatment. Vinicius himself admitted as much: “And it was in Paris… that I met the producer Sacha Gordine, who was interested in the story and wanted to make a movie of it. So it was really the movie that made possible the staging of the play…”

Orfeu (orfeu.eventbrite.com)

On the face of it, though, Diegues’ 1999 re-filming does come closest to actually carrying out, to a limited extent, the poet’s intentions, more than adequately preserving the systemic violence of the hills that was markedly absent from Camus’ freshly scrubbed reading. He even threw in Orfeu’s parents as a good-will gesture to the original.*

That said, neither picture even remotely approaches Orfeu da Conceição’s lyrical foundation, its soul-stirring poetic imagery, or its classical refinement and construct. That the piece intermittently betrays melodramatic overtones, seriously over-playing its hand when it comes to the emotional and physical state of the title character’s suffering and distress (think Milton’s Samson Agonistes) makes it a major liability.

Only Jobim’s perfectly-limned musical responses keep it from wallowing in its own excess. About the worst that could be said of his score was that it was too tasteful and refined for such violent displays of passion.

Factor in a whopping Fat Tuesday celebration and a healthy dollop of Afro-Brazilian dance sequences, choreographed by the debuting Lina de Luca, and voilá: you have the makings of a total work of art, a stunning stage realization (albeit in primitive form) encompassing a veritable periodic table of theatrical elements — drama, music, poetry, dance, setting, and scenic and lighting design — with all the pomp and majesty, as well as the flaws, inherent in that much-bandied-about term “opera,” or, in this case, “drama with music,” which is a more accurate description.

Orfeu da Conceicao (bossa.mag.spaceblog.com.br)

Does everything that has been written about Orfeu da Conceição make it the Brazilian musical to end all musicals? No, not necessarily. Should we continue to hold out hope, then, that Orfeu might one day be restored to his proper place on the world stage? Anything is possible, if the opportunity were ever to arise. (Broadway producers, take note.) But, as we have tirelessly strived to point out to readers, Vinicius de Moraes was incontrovertibly put in the awkward position of having to bear witness to the cinematic “decimation” of his most-prized work.

The record clearly shows that Vinicius walked out on the Brazilian premiere of Camus’ Black Orpheus, the first of two film adaptations. Doesn’t it seem odd, though, that the world-weary poet would have survived such a profound jolt to his system by the palantir-like glimpse he was afforded of the future misdirection of his country — where it was headed and how those in the public trust conspired to keep it off course — only to lash out in the one way an artist of his standing could lash out: by taking the “law” (or his feet) into his own hands, as the situation demanded?

That’s an awfully big “maybe,” when you come right down to it. In support of his own modern view of the ancient Greek fable, director Diegues took care not to disturb the playwright’s easily offended fans (get thee behind me, Dama Negra!). “In the original play,” he argued, “there’s a poem in which Vinicius says that everything in the world dies except for Orpheus’ art, which is forever — and I tried to visualize that.”

The actual lines, which are given to the members of the chorus and form the basis for the play’s ontological outlook and conclusion, vary somewhat from his recollection but are no less inspiring:

Para matar Orfeu não basta a Morte.

Tudo morre que nasce e que viveu

Só não morre no mundo a voz de Orfeu.

To kill Orfeu, Death is not enough.

Everything that is born and lives must die

In the world only Orfeu’s voice survives.

It is incumbent upon us to insist that, even if the country itself were to fall off a cliff — which, in as much as it pained The Little Poet to learn, it very nearly did at key moments in its recent past — Orfeu’s voice (and, by suggestion, Brazil’s music) would live on in the world as well.

* * *

One of Vinicius’ closest contemporaries, writer and poet Carlos Drummond de Andrade, offered this discerning opinion of his friend: he was “the only Brazilian poet,” Drummond decreed, “who dared to live under the sign of passion. That is, of poetry in its natural state.” Orfeu da Conceição, Moraes’ most ambitious literary and musical creation, was the complete fulfillment of this sign of passion, his poetic and unvarnished imitation of slum life in its natural state. God help the person who came between him and that passion!

Author Lúcia Nagib’s Brazil on Screen: Cinema Novo, New Cinema, Utopia goes into excruciating detail on the “natural state” of writer-director Carlos Diegues’ passion for Orfeu. One scene, in particular, has a special poignancy for her:

“As the film draws to a close, the favela hill returns to its everyday violence after the ‘great illusion of carnival’ [sic] is over, as sung in ‘Felicidade,’ a song by Jobim and Vinicius, delivered with innocent simplicity by Jobim’s adolescent daughter, Maria Luiza Jobim, who plays a minor role in the film.”

The opening line of that number, which happens to fit in perfectly with this post’s main heading — and which is also the first one to be heard in the French-made Black Orpheus — is simplicity itself, yet speaks volumes of the illusory effect the annual ritual of Carnival has had on the lives of the poor:

Tristeza não tem fim

Felicidade sim

A felicidade do pobre parece

A grande ilusão do carnaval

A gente trabalha o ano inteiro

Por um momento de sonho

Pra fazer a fantasia

De rei ou de pirata ou jardineira

Pra tudo se acabar na quarta-feira

Sadness has no end

Happiness does

A poor man’s happiness is like

The great illusion of Carnival

You work all year long

For a brief fulfillment of a dream

To play the part of

A gardener, a pirate or a king

Only to have it all end on Wednesday morn

What cannot be deemed a “great illusion” is Carnival’s restorative power; how its raw, incessant energy seems to electrify every one of the parade participants gathered, in spite of four solid days of nonstop action and fun. After a highly favored samba school falls to a lesser rival; after the drums go silent and the crowds begin to disperse, you’re awakened from “a brief fulfillment of a dream” to the reality at hand.

It’s the same instinctive feeling Vinicius must have sensed when he first realized what had been wrought upon his carioca tragedy. It is not a pretty sight, what with all those drained and disappointed faces. But hey, there’s always next year, which is another way of saying that “happiness” will return to them — in some way, shape or form — se Deus quiser, or “God willing,” an everyday Brazilian expression; along with the other assorted rituals of one’s existence: births, deaths, anniversaries, baptisms, weddings, funerals, and what have you.

Life has a continuous ebb and flow — a beginning and an ending — and “sadness,” as our title implies, is just an orderly part of that flow. In that respect, the melancholy air, “A Felicidade,” could never have been able to bookend Black Orpheus and the much-later Orfeu, much less come to the fore, had it not been for the sublime music of bossa nova. What is more, bossa nova could never have achieved the worldwide fame and recognition it doubtless deserved without the fortuitous teaming of Jobim with Moraes, the irrepressible partnership that started it all.

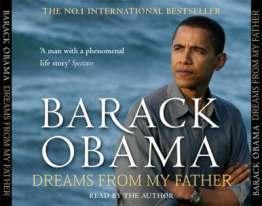

Barack Obama, “Dreams from My Father”

In Barack Obama’s autobiographical Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance, he specifically mentions Black Orpheus by name as “the most beautiful thing” his mother had ever seen. “The film, a groundbreaker of sorts due to its mostly black, Brazilian cast, had been made in the fifties. The story line was simple: the myth of the ill-fated Orpheus and Eurydice set in the favelas of Rio during Carnival. In Technicolor splendor, set against scenic green hills, the black and brown Brazilians sang and danced and strummed guitars like carefree birds in colorful plumage.

“About halfway through the movie,” he continued, at almost the exact spot that Vinicius had gotten up and left the screening, Obama decided that he had “seen enough, and turned to my mother to see if she might be ready to go. But her face, lit by the blue glow of the screen, was set in a wistful gaze. At that moment, I felt as if I were being given a window into her heart, the unreflective heart of her youth. I suddenly realized that the depiction of childlike blacks I was now seeing on the screen, the reverse image of Conrad’s dark savages, was what my mother had carried with her to Hawaii all those years before, a reflection of the simple fantasies that had been forbidden to a white middle-class girl from Kansas, the promise of another life: warm, sensual, exotic, different.”

Here’s one simple fantasy we might consider setting by the wayside: if there is anyone out there who winds up in the same, awkward position a temperamental Brazilian poet — or a future U.S. president — once found himself in, let him declare, here and now, he will not slip out of the movie theater… no matter what happens inside. ☼

Copyright © 2013 by Josmar F. Lopes

* The role of Orfeu’s mother — in this version, called simply Conceição — was played by veteran actress Zezé Motta, who in her earliest days as an ingénue played the lead in director Diegues’ first big international screen success, the feature Xica da Silva from 1976.