I’ll be upfront: I’ve yet to really read any John Ruskin. A British art critic in the nineteenth century, a well-travelled Oxford scholar, a prolific writer and a collector of observations—I was curious as to why a man who drew unceasingly his entire life would be branded an ‘amateur,’ and that even so he might be presented as ‘an outstanding artist in his own right,’ as the National Galleries of Scotland recently presented him in a dedicated exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh.

While the gallery notes proclaim, ‘Drawing for Ruskin was an analytical process and represented an opportunity to mediate on many aspects of the physical world,’ sentiments I that resonate strongly with me and my own predilection for drawing, his preoccupations seem to be more with the surface detail of things—column tops, archway ornaments and the correct shape of leaves. Very rarely do his drawings and watercolours come together as images. It became apparent very quickly during my visit to this show that Ruskin worked not as an artist, but solely to document intellectual curiosities. This is a fine task in itself, and it is laudable that Ruskin found a notation in drawing that enabled him to gather data from the physical world for further reflection, study and publication. What is discomfiting, then, is that a state gallery might conflate this visual collection with art. And that the members of the public shuffling around me might attribute awe-inspiring skills to the originator of a spread of drawings which I found largely fussy, weak and lacking either insight or confidence.

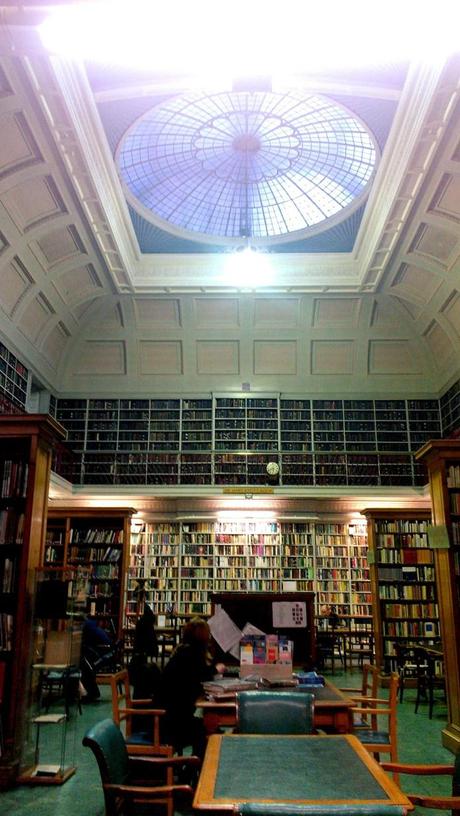

Literary and Philosophy Library, Newcastle upon Tyne

On revisiting Newcastle upon Tyne and discovering the glorious little haven of the Literary and Philosophy Society Library, I stumbled across a little volume by Marcel Proust, an introduction to his own translation of one of Ruskin’s written works, and was very curious to learn of Proust’s adoration of Ruskin. Proust’s gentle, meandering words ushered me more firmly down the pathway of my own reflections. ‘To what extent this wonderful soul faithfully reflected the universe,’ gushes Proust (1987: 49), ‘and under what touching and tempting forms falsehood may have crept, in spite of everything, into the heart of his intellectual sincerity, is something we will perhaps never know.’ Proust (1987: 32) describes how Ruskin’s many guises led to many conflicting things being said about him, and how these contradictions made Ruskin himself appear contradictory and dubious. Yet in Proust’s eyes, Ruskin pursued only beauty, and caused his art and his science to submit to the dictates of beauty. Accused of letting imagination run wild in science, and of binding up art in scientific tethers, Ruskin saw the task of both as akin to the high calling of the poet: ‘a sort of scribe writing at nature’s dictation a more or less important part of its secret, the artist’s first duty is to add nothing of his own to the sublime message’ (Proust, 1987: 31; 34).

His best works on display in Edinburgh were without a doubt Mountain landscape, Macugnage (1845) and Crossmount, Perthshire; Study of crag, tree and thistle (1847), both sepia studies which blaze like beacons for their sheer strength as pictures. The former is my first encounter with a Ruskin landscape that dissolves atmospherically into the distance, and to great effect; the latter bulges from the center in a rare expression of depth. At times one is delighted with his feeling for colour, and his ability to weave a peaceful color harmony. Rocks and ferns in a wood at Crossmount, Perthshire (1847), which graces much of the promotional material, translates well into print, largely because of the soothing purple-green-blue amalgam of foliage. There is even something startlingly delightful about the dramatic twist of the trees from his viewpoint, something dreamily unsettling like a rolling William Robinson painting. But even here, one pleads with Ruskin; he is still so shy to lay down his marks. Botanical precision wins out as he carefully colours around pointed ferns, cautious to leave white paper for the paler fronds to be filled later. One does not frown upon precision; but his meticulous marks exhibit a fear of error rather than a certainty in what he has seen and a conviction in what he aims to record.

Mountain landscape, Macugnage, by John Ruskin (1845)

I read with horror but not surprise a passage of Ruskin’s writing selected and abridged by Proust (1987: pp. 30-31):

‘Every class of rock, every kind of earth, every form of cloud, must be studied and rendered with equal precision. … Every geological formation has features entirely peculiar to itself; definite lines of fracture, giving rise to fixed resultant forms of rocks and earth; peculiar vegetable products, among which still farther distinctions are wrought out by climate and elevation. In the plant, the painter observes every character of color and form, … seizes on its lines of rigidity or repose, … observes its local habits, its love or fear of peculiar places, its nourishment or destruction by particular influences; he associates it … with all the features of the situation it inhabits …’ {Modern Painters, CW 3: 34-48} … ‘The greatest picture is that which conveys to the mind of the spectator the greatest number of the greatest ideas.’ {Ibid., CW 3: 92}

What ghastly sort of aesthetic utilitarianism demands the maximum communication of messages visually? Perhaps one who had so much to say had not the luxury of meditating on a single idea, and offering it elegantly and succinctly to his audience. Ruskin’s visual verbosity matches his literary manner, and his task differs dramatically from ours as artists. But as artists, we have far more to bring to our canvases than precise transcription.

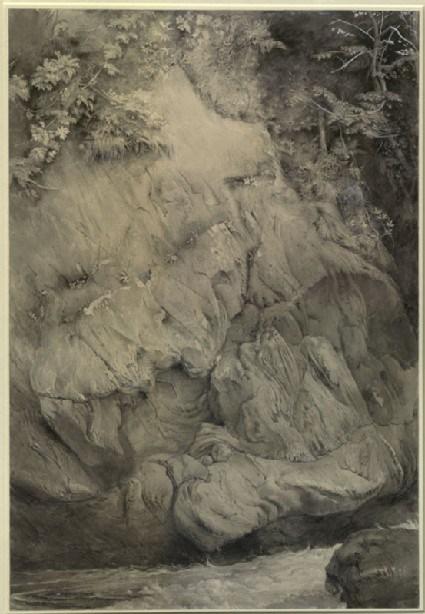

Study of a Gneiss Rock, Glenfinlas, by John Ruskin (1853-4)

Study of a Gneiss Rock, Glenfinlas (1853-4), painted in Scotland, more successfully merges Ruskin’s penchant for scientific details and an artistic sentiment. The details of the foliage at the top add to, rather than detract from, the greater image: the picture is solid. But what can we say of this oddity? Is it nothing more than a fluke? Having achieved this synergy between his desire to record fact and the production of a solid picture, one hopes against hope that Ruskin will surge onwards, equipped with this new skill, and at last emerge as more than an amateur. But alas, this work seems an anomaly in his tireless output.

Oxford

A pair of his notebooks which are on display in a cramped corner might have served as a better focus for an exhibition on such a complex character as Ruskin. The notebooks quietly plead, ‘Let’s remember him as a collector, curious and interested, and not try to cloak his endeavours in ‘artistic impulse.’ I sense, rather than being compelled by any true artistic impulse, that Ruskin would have preferred to record all he saw with absolute truth and precision, had he the ability. He simply had no interest in imposing design on the natural world or in introducing visual lies for a pleasing quality of linework. More than anything, one senses his fear at failing to record nature with the utmost, unartistic truth in his timid pencil strokes and panicked application of watercolour. The pencil—a glorious medium in its own right—is abused as a crutch by Ruskin, who scratches an uncertain scene in graphite before tentatively filling the shapes with a wash of color. Nowhere does he seem to use it as a guide for more assured brushwork; almost nowhere does he trust himself to simply apply paint. Everywhere, the skeleton of pencil is showing through—except in two notable, tiny feather paintings: Study of a peacock’s breast feather (1873) and Three feathers (1875). At last he stops scratching and picking, plucks up the courage to abandon his pencil, applies his infinitely fine brush with precision, and forces himself to draw well. I wish only that he had the courage to work this way more often.

Ruskin School of Art, Oxford

Now, it may be true that Ruskin did not promote himself as an artist, but rather as an intellectual. His efforts in drawing were solely for his own improvement, his own engagement with and meditation on the external world. Nonetheless, seeing a show like this is extremely disheartening, for Ruskin was tutored in drawing from an early age, having demonstrated reputed precocious ability; he evidently devoted countless hours to the activity, toting not merely a small sketchbook for opportunistic scribbles but large and unwieldy sheets of paper in a determined effort to go out drawing. And let’s not gloss over the fact that he sat as the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University in 1869, going on to found his own school, The Ruskin School of Fine Art and Drawing, also at Oxford, shortly after in 1871. What is troubling about Ruskin, this jack-of-all-trades, dabbling in everything, is that evidence points to him more than simply dabbling in drawing, and yet never attaining a level of true accomplishment. Is hard work and undying curiosity not enough? Or is the lesson of Ruskin not to spread yourself too thinly?

Ruskin School of Art, Oxford

The reception of the public was equally worrying, with the near-exclusively grey-haired visitors full of clever things to spout admiringly in Ruskin’s direction. Even with the marked contrast of John Everett Millais’s dignified and pictorially lovely 1854 portrait of the man, also painted at Glenfinlas in Scotland. One can’t help but think that celebrating an amateur is a relief and a comfort to the unaspiring layman, whose weak efforts might just as easily be described as ‘exquisitely detailed’ and ‘the result of an intense and passionate artistic impulse’ by gallery pamphlets. And that would be a real shame, for in celebrating art that is less than awe-inspiring, we set lower standards for the artists of our own time, who then need to do so little to bewitch an undiscerning public—which, arguably, is the great artistic malaise of our day.

Oxford

Proust, Marcel. 1987. On reading Ruskin: Prefaces to La Bible d’Amiens and Sésame et les Lys with selections from the notes to the translated texts. Trans. Jean Autret, William Burford and Phillip J. Wolfe. Yale: New Haven.