What Was Mine To Do

Written by Dustin Spence

Directed by Doug Long

Side Project Theatre, 1439 W. Jarvis (map)

thru Oct 7 | tickets: $10-$15 | more info

Check for half-price tickets

Read entire review

Excellent performances overcome clichéd script to capture our attention

Strangeloop Theatre presents

What Was Mine To Do

Review by Joy Campbell

Set in Chicago and Afghanistan at the time of the 2008 presidential election, What Was Mine to Do purports to examine journalistic ethics in America by considering how the actions of some Chicago TV journalists affect the fate of a U.S. soldier and a reporter captured by the Taliban. According to the Director’s Note, the play looks at “ethical questions of what journalists should and shouldn’t report, and how personal agendas can affect those reports…”

While this may be an attractive premise, the play, while superbly performed, unfortunately never really explores it in an original or plausible way.

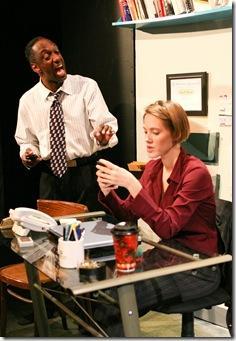

The play opens in Chicago, where we see a TV-news office abuzz with election-coverage energy. A young producer has learned (via a conveniently anonymous source) that an attack on U.S. military has resulted in the capture of a soldier and a reporter embedded with the soldier’s unit. The producer wants to run the story, believing it newsworthy. That she took a class under the reporter in journalism school is presented as personal motivation to pursue the story, as she hopes to bring attention to the situation and in doing so prompt his rescue. Her boss forbids her to run the story; she, as it turns out, had mentored the reporter in his early days, and is concerned that any attention might endanger his life. She also doesn’t want to run anything not pertaining to the election. Enlisting the aid of the anchorman, the young producer breaks the story anyway. Drama ensues.

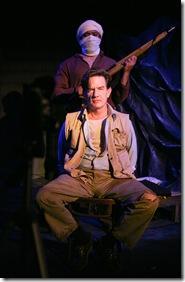

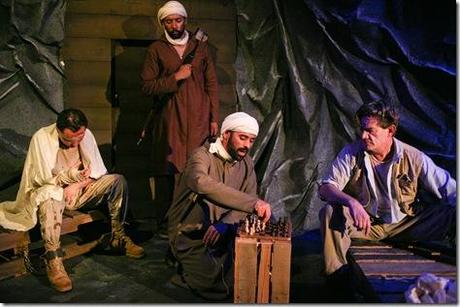

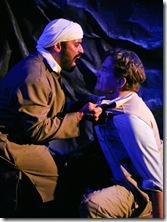

In Afghanistan, the captors and their prisoners conflict predictably. The young soldier has been blinded in the attack. He is angry and frightened, and contends ceaselessly with his captors. The reporter serves as a protective father figure and the voice of moderation, and he and the leader of the Afghan captors engage in the kind of complicated relationship that develops between two men of honor. When word gets out of the news story, however, things get a little out of control.

The script has its problems. The issue of journalistic ethics vs. personal agenda is never really developed, nor do we ever receive a clear explanation as to why breaking a story on a reporter missing in Afghanistan is somehow subversive and radical. It’s suggested that the reporter is a kind of traitor for wanting to cover “the real truth about the war,” but this is hardly a novel notion, and if he were such a security threat, why did the U.S. military allow him to be embedded with one of its units? We are also asked to believe (I didn’t quite understand which) that it’s the release of this story that will either inform the U.S. government and thereby move it to action to recover these men, or motivate the U.S. government to recover these men by making it a popular cause. The counter-argument for this is that it’s an election year so the story would be unpopular, but this just makes no sense. If there is another reason, I missed it, or the script is unclear. Likewise, the boss’s assertion that breaking the news will also endanger the reporter is made with no real supporting argument, or if one is made, it gets lost in the shouting.

In Afghanistan, the leader of the captors tells the reporter that he wants him to be “the voice of the West” and videotapes him, but we never really understand the purpose, except for some vague implication that he is trying to get the West to see the Afghan’s human side.

|

There is little in the way of character development. On the Chicago side, we see lots of conflict and drama, but never scratch beneath the surface of what really drives the characters; pat, expository self-descriptions substitute for complexity and insight.

In Afghanistan, it’s not revealed what drives reporter Frank, although his many exchanges with fellow prisoner Toons provide ample opportunity. A scenario testing Toons’s humanity is a nice effort, but the situation feels contrived and the outcome predictable.

Taliban leader Kamil engages Frank in a game of chess as an exercise in explaining poetically his perspective on the futility of the conflict. While using chess as a metaphor for conflict is not very original, his character nevertheless makes some astute observations. Still, if the goal is to help us understand that Afghans – even Taliban – are People Just Like Us (if you bomb us, do we not bleed?) with complex emotions, a sense of moral justice and loss, and a legitimate point of view, it hardly serves that purpose to represent them as two distinct caricatures: one a courtly, well-mannered (and English-speaking) chess-playing philosopher; the other his thuggish, impetuous, Pashto-speaking henchman ever ready to do grievous bodily harm.

Also, it’s permissible to address shopworn themes (the duty of the media to inform vs. the responsibility of the media to avoid reckless damage in service to The Truth; disobeying authority in the pursuit of justice; enemies discovering their mutual humanity when forced together) if you present them in a way that brings fresh insight or perspective; unfortunately, the treatment of these themes via clichéd circumstances and stock types provides us with very little that is revelatory.

Despite the script’s flaws, however, good, natural dialogue and believable relationships between the characters on both sides allow us to invest in them. Excellent performances also make the show engaging: Kate Black-Spence does a terrific job as Claire, the cocksure young producer whose good intentions turn into big regrets when the repercussions of her actions surface. Denise Blank delivers an outstanding performance as the hard-bitten boss, Candice (”The Pope”) Gregory, struggling between her personal affection for the lost reporter and her desire to be an ironhanded professional. Matthew Lloyd as sassy anchorman Thomas Carter is at times almost too self-consciously cute, but nevertheless does a highly entertaining job of conveying his character’s underlying cynicism through a veneer of humor that keeps the audience smiling.

Andy Quijano’s Staff Sergeant Antonio “Toons” Cruz has a tough job: convey plenty of passion, anger, and fear while blindfolded and handcuffed to a bed by the ankle. To his credit, he succeeds. Monnie Aleahmad as Dadullah, one of the two Taliban captors, also has his work cut out for him in conveying a non-English-speaking character through gestures and Pashto alone. He employs his physicality and his expressiveness well. Colin Reeves plays reporter Frank with a low-key approach that works somewhat as a nice contrast to Quijano’s amped Toons, but which at times seems almost too distracted for the intensity of the situation. Gustavo Obregon is excellent as Kamil, the gracious, honorable Taliban leader.

At 2 hours with intermission, the script does need some cutting and tightening. To its credit, however, the show’s wonderful performances and commitment to character had me wanting to buy into it; I believed that this company wanted to tell a good, entertaining story, and with some trimming and fleshing out of the plot and the characters, What Was Mine To Do shows promise of achieving that goal.

Rating: ★★★

What Was Mine To Do continues through October 7th at Side Project Theatre, 1439 W. Jarvis (map), with performances Thursdays-Fridays at 8pm, Sundays at 2pm. Tickets are $10-$15, and are available by phone (773-757-6689) or online through BrownPaperTickets.com (check for half-price tickets at Goldstar.com). More info at StrangeloopTheatre.org. (Running time: 2 hours, includes an intermission)

Photos by Austin D. Oie

artists

cast

Monnie Aleahmad (Dadullah), Kate Black-Spence (Claire O’Donell), Denise Blank (Candice Gregory), Matthew Lloyd (Thomas Carter), Gustavo Obregon (Kamil Shah), Andy Quijano (Sgt. Antonio “Toons” Cruz), Colin Reeves (Frank Bernhardt)

behind the scenes

Doug Long (director); Glen Anderson (set); Libby Beyreis (violence design); Ben Campana (props); Carrie Campana (costumes); Cat Davis (lighting); Zack Florent (graphics); Brad Gunter (production manager); Austin D. Oie (photos); Lisa Uhlig (stage manager); Jason Weinberg (sound design)

12-0915