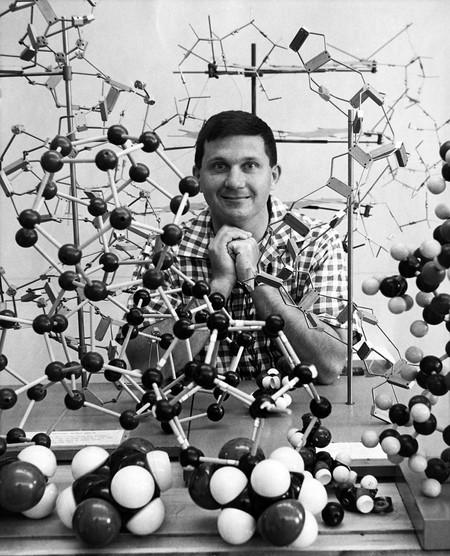

Richard Marsh, 1960. Credit: Caltech Archives.

At the beginning of this year, on Tuesday, January 3rd, the highly accomplished crystallographer Richard E. Marsh passed away at the age of 94. During his impressive sixty-six-year career at Caltech, Marsh was influenced greatly by Linus Pauling’s work in crystallography, and eventually collaborated with him throughout the 1950s and early 1960s. Colleagues and admirers alike knew Marsh for his rigorous standards in investigating atomic structure, a discipline that resulted in his determination of over one-hundred crystal structures throughout his career and the improvement of at least that many more.

In a Caltech tenure that spanned more than six decades, Marsh also inspired generations of graduates and undergrads alike, teaching valuable techniques in crystallography and instilling in his students the rigor of his own research practice. His course “Methods of Structural Determination” was among the most popular graduate offerings in the Institute’s Chemistry division for a great many years. He leaves behind an impressive legacy for the crystallographers of today.

Marsh, who went by Dick, was born in 1922 in Jackson, Michigan. By the time that he arrived at Caltech as an undergraduate in 1939, Pauling had already helped to established the Institute as among the premiere destinations for budding young crystallographers around the world. In particular, Pauling’s newly published Nature of the Chemical Bond had transformed crystallography from arcane to fundamental.

Though Pauling was certainly well known on campus when Marsh was an undergraduate, it would be another eleven years before Pauling and Marsh formally crossed paths. As a student, Marsh had identified an interest in chemistry, but hadn’t narrowed to a particular focus. He commented later that a technical drawing course at Caltech served as a precursor to his interest in crystallography. He graduated with his BS in applied chemistry in the midst of World War II (1943) and, upon graduation, enlisted in the US Navy, spending the next two years degaussing ships in New Orleans. This is where he met his wife Helena Laterriere, to whom he remained married for nearly seventy years.

Following his discharge, Marsh enrolled in graduate school at Tulane University so that he might remain in close proximity to his fiancée. Most of the courses that he needed were already full at the time of his enrollment, so Marsh signed up for an X-ray crystallography class at the nearby Sophie Newcomb College for women. It was there that he met the teacher who changed his life and cemented his interest in crystallography.

That teacher, Rose Mooney, had previously attempted to enroll at Caltech for graduate studies only to be turned away when she arrived in Pasadena and the administration realized that she was a female. Pauling himself stepped in at this point, giving her a temporary position in his laboratory until she was accepted into the graduate program at the University of Chicago. Her lab at Sophie Newcomb College was quite modest, containing only a Laue film holder and one x-ray tube, but for Marsh it was enough. Inspired, his course was set from then on, though he’d have to travel across the country to continue it.

After marrying Helena on August 11, 1947, Marsh enrolled at UCLA. He later called the 2,000-mile move across the southern United States the beginning of their honeymoon, joking that it was a wedding present to his new bride. At UCLA, Marsh studied crystallography under Jim McCullough and earned his Ph.D. in 1950. Caltech subsequently offered him a post-doctoral research appointment, and he remained at the Institute for his entire career, always in a non-tenured position until his retirement in 1990, when he named an emeritus professor.

In the years immediately following World War II, Caltech was still very much the place to be for crystallographers. Thanks largely to Pauling, who returned to structural chemistry after his own war projects had wrapped up, scientists from all over the world traveled to Pasadena to conduct research and solve structures.

Marsh finally became associated with Pauling in 1950, when he arrived at the Institute as a post-doc. He published his first paper with Pauling, “The Structure of Chlorine Hydrate,” in 1952. A year later, the duo published “The crystal structure of β selenium,” which marked the first time that Marsh issued a correction of someone else’s work. Indeed, over the course of his career, Marsh became increasingly focused on policing the field for errors, always striving for maximum accuracy and precision. Pauling engaged in this work himself from time to time, although the various demands on his attention kept him too busy to make a full-time habit out of it.

Marsh at the famous Caltech Proteins Conference in 1953. To his right is Francis Crick.

Pauling and Marsh continued to collaborate on a number of other publications related to atomic structure between 1952 and 1955, at which point their interests began to diverge. Nonetheless, the two retained a degree of professional closeness throughout the following decades, often writing to compliment one another on various accomplishments, solicit advice, or suggest future projects. In one instance, Pauling provided the kernel of an idea that resulted in Marsh’s 1982 paper on N, N-Dimethylglycine hydrochloride. Likewise, Marsh helped pave the way for Pauling to publish one of his own articles in Acta Crystallography, where Marsh served as an editor for seven years.

In 1975, presented with the problem of solving of a compound that generates hydrazine from molecular nitrogen, Marsh devised and shared a method for determining the structure. This solution influenced the direction of study into hydrazine formation, creating the opportunity for further study. And although Marsh continued to solve structural problems in the years that followed, he also devoted countless hours – over half his career – to the pursuit and correction of published errors, usually pertaining to inaccurate space groups in important crystal structures. Pauling later described Marsh as the “conscience of crystallography.”

With time, he gained such a reputation that his colleagues in the field were perpetually anxious that they would be “Marshed,” or taken to task, for their errors. Marsh held his colleagues accountable to their calculations and believed firmly in checking a computer’s work, rather than the other way around. He is remembered today as having been responsible for many refinements in crystallographic discipline and for the high standards that make future refinements possible.

Marsh in 2012. Photo by Rafn Stefansson.

In terms of organizational involvement, Marsh joined the American Crystallographic Association (ACA) shortly after starting at Caltech. Over the duration of his career, he became increasingly active in the group, and ultimately served as its president in 1993. He was also co-editor of Acta Crystallography from 1964-1971.

Marsh’s classroom lectures and his relationships with students were at least as influential as were his publications in crystallography. One colleague, B.C. Wang, recalled that Marsh summoned crystallographers of all stature – be they students, professors, or visiting scientists – to a group coffee at 10:30am every day, to encourage discussion and advancement within the field. Students also remembered him as critical but encouraging, his commitment to student success serving as an inspiration for their own hard work.

Marsh and Pauling in 1986. Credit: Caltech Archives.

When queried by CRC Press in the early 1990s for his input on future publications, Pauling suggested that the press solicit a monograph from Marsh on the crystal structures that he had corrected thus far, arguing that a volume of this sort might help future crystallographers to avoid these errors. Pauling then wrote to Marsh, inquiring about the total number of crystal structures that Marsh had indeed corrected. Pauling had guessed that Marsh had published fixes for 25 to 30 structures and was surprised to learn that the actual number was between 110 and 120.

Although Marsh didn’t publish this proposed monograph, Pauling’s idea evidently inspired him. In 1995, he authored a substantial article on the subject, titled “Some thoughts on choosing the correct space group.” In the piece, Marsh discussed common types of errors as well as preferable techniques and methodology, including a few tables that documented space group revisions over time.

While at Caltech, Marsh worked closely with Verner Schomaker, another of Pauling’s graduate students. In 1991, the two teamed up to put together a festschrift honoring Pauling’s early work on crystallography. Pauling, a man who, by then, had received basically every award that a scientist can get, was immensely pleased and grateful for this honor.

In 2003, Marsh received the inaugural Kenneth Trueblood Award from the American Crystallographic Association for his outstanding achievements in chemical crystallography. Few other awards could be more fitting for a crystallographer of Marsh’s caliber and commitment. In announcing the prize, the chair of the selection committee identified Marsh as a “rare individual among crystallographers, an outstanding teacher and researcher who has greatly influenced so many students and faculty.” He will be remembered and missed for this indefatigable integrity, dedication, and mentorship.

Advertisements