I love childhood memoirs. As someone who often rhapsodies about the sun-soaked halcyon days of childhood summers, spent lying spreadeagled on the cool grass beneath the trees in my garden, dappled light spotting across my nut-brown limbs as I turned page after delicious page of Malory Towers books in a heavenly haze of seemingly endless days, I find it a wonderful leveller that all of us seem to remember only the golden moments of our youth. Childhood to me is inherently seasonal: waking up to my pink-suffused bedroom in spring as the sunlight shone through the cherry blossom trees outside; running barefoot around the garden in the summer, the smell of the barbecue lingering in the air; crunching through the piles of leaves on my way to school in the autumn, constantly on the lookout for fallen conkers to pickle in vinegar and thread onto a string; curling up on the sofa with hot chocolate on dark winter afternoons. I don’t remember the boredom, or the fear, or the anger, though I’m sure I must often have felt all of those things. As I get older, my childhood becomes ever more a jumble of delights, and I find that most memoirs (other than the misery type, of course) tend to present childhood in just such a way too. I hoped for this view of childhood when I picked up Period Piece in a second hand bookshop a few weeks ago, as I’ve long heard of it being wonderful. What I didn’t realize until I started reading is that Gwen Raverat was the granddaughter of Charles Darwin, and so the childhood she describes, moving between the large houses in Cambridge populated by a myriad of Darwin uncles and aunts and cousins, London homes of more well known aunts and uncles, and the Darwin family home in Downe, Kent, is made even more fascinating by its proximity to the intellectual great and good of the Victorian age. What makes it so successful, though, is not this touch of stardom, nor the vanished world of servants and horses and carriages she depicts, but Raverat’s incredible eye for detail, her wonderful sense of humour, and her ability to choose the moments of childhood joy and rebellion that we can all relate to, no matter when we were born.

Raverat grew up in a huge house on the river in Cambridge, which still stands and is now part of Darwin College, with several siblings, a flighty American mother and a much older father, who was the son of Charles Darwin. Most of her father’s siblings, along with her father, were involved in university life in some way, and so much of the Darwin family were neighbours, and lived closely intertwined lives. Known for marrying late, the Darwin sons had their children at about the same time, which made a merry gang of cousins with whom young Gwen could rampage freely about the streets of Cambridge. She describes a city that seems an impossibility now; still largely rural, surrounded by fields and meadows filled with sheep and cows, streets lined with tumbledown cottages, large mills and granaries, and all of it connected by the river, which many people still used as the most convenient way of getting around rather than taking a horse and carriage into the congested centre, clogged with chattering crowds of gowned students. However, it was the descriptions of the minutiae of daily life that delighted me the most, from the specifics of just how many underclothes people used to wear to the etiquette of dinner parties, to what was eaten at lunchtime to how often people went shopping, this is an invaluable resource for understanding the everyday lifestyle and attitudes of the late nineteenth century middle class. What is so amazing about everything that Raverat describes is how alien it is, and yet still within living memory for someone alive in the middle of the twentieth century. To have grown up in a world where aunts regularly died in childbirth, where women did nothing but pay calls all day, where there was nothing to do in the evening but read or sew, where there was a different type of servant for every household task and unmarried women had to be chaperoned everywhere and yet live an adult life amongst cars and televisions and telephones and aeroplanes must have been utterly amazing.

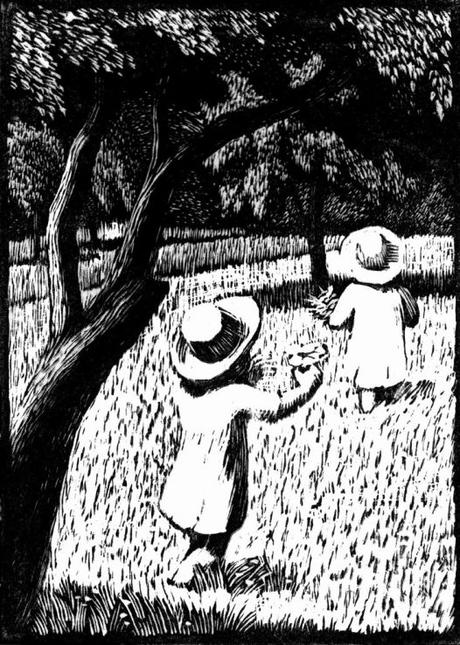

With a wry and affectionate sense of humour, Raverat brings the eccentric members of her family and their circle fully alive. Her accounts of family picnics in the meadows, idyllic summers at Downe, listening to the plop of mulberries falling from the tree outside her bedroom window, endless hours of playing on the green-tinged river under the canopies of willow trees, sitting in fire-lit drawing rooms listening to the talk of bearded uncles and the rustling dresses of extravagantly attired aunts and watching the horse-drawn world pass by in front of her windows are totally charming and a truly fascinating and enlightening glimpse into a forgotten world. It reminded me very much of Dorothy Whipple’s frustratingly hard to get a hold of autobiography, as well as Laurie Lee’s Cider with Rosie; all beautifully written, magical tales of the wonders of childhood, which remains timeless in its delights and disappointments. I can’t recommend it highly enough!

Advertisements