Father Georges Dominique Pire with a map and model of refugee villages in Europe.

[Ed Note: Today we begin an in-depth examination of Linus Pauling’s activism in opposition to the Vietnam War. This is post 1 of 7.]

“Our present object is not to apportion blame among the groups of combatants. The one imperative is that this crime against all that is civilized in the family of man shall cease.”

-“An Appeal by Recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize,” 1965

On the 27th of April, 1965, Father Georges Dominique Pire wrote a letter to all of his fellow Nobel Peace Prize recipients from Aberdeen, Scotland. The letter intended to rally this group in opposition to the Vietnam War. At the time, public opinion in the United States overwhelmingly supported the recent deployment of troops to Vietnam, as ordered by President Lyndon Johnson.This commitment would be increased by December, bringing the total number of U.S. military personnel in Vietnam to nearly 200,000.

Linus Pauling, who had been awarded the Peace Prize in December 1963 for his work ushering in a partial nuclear test ban treaty, read Pire’s letter with a heavy heart. Pauling had received notification of his award just as President John F. Kennedy began to increase American involvement in Southeast Asia, and only a month later the President was assassinated. This series of events paved the way for a new Commander in Chief, Lyndon Johnson, to further expand the American presence in the region.

By 1965, with casualties mounting and the political landscape becoming more polarized, Father Pire implored his fellow Peace Prize laureates to act in whatever capacity they might muster on behalf of peace for all of humanity. A Belgian friar who had fled the German advance during World War II, Pire knew first-hand the horrors of combat and had practiced – as well as preached – his message of peace by providing aid to refugees. In addressing the Peace laureates, the friar formed his lengthy letter around the story of Cain and Abel as recorded in Genesis, the first book of the Bible.

Then Cain said to his brother, “Let us go out together,” and while they were out in the open, Cain turned upon his brother Abel and killed him. Then the Lord said to Cain, “Where is thy brother, Abel?” Cain said, “I cannot tell. Is it for me to keep watch over my brother?” But the answer came, “What hast thou done?”

As Pire’s retelling of the story concludes, the Lord says, “The blood of thy brother has found a voice that cries out to me from the ground.”

For Father Pire, it was the blood that was being spilled in Vietnam that had a voice. “Each one of us must be ready to reply to this question which is put to us all,” he said. “You now have a line of conduct to follow – to be the voice of the voiceless, to give the strong a guilty conscience, to sensitize public opinion, to show your brothers the way by walking straight yourselves.” It was a call that did not fall on deaf ears, and Linus Pauling in particular took up the mantle of peace in a personal crusade against the violence escalating in Vietnam.

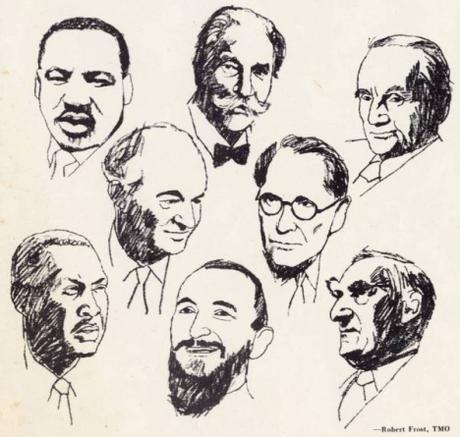

Drawing of the eight Nobel Peace laureates who signed the 1965 Vietnam appeal. Clockwise from top: Albert Schweitzer, Norman Angell, Philip Noel-Baker, Boyd Orr, Georges Dominique Pire, A.J. Luthuli, Linus Pauling, Martin Luther King, Jr.

In August 1965, eight out of the ten living Nobel Peace Laureates signed a joint plea urging the cessation of hostilities in Vietnam and urging the world to reach an accord on Southeast Asia. This historic appeal was signed by Sir Norman Angell, Lord Boyd Orr, Dr. Albert Schweitzer, Father Georges Dominique Pire, Philip Noel-Baker, Chief A. J. Luthuli, Linus Pauling, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Only Prime Minister Lester Pearson of Canada and United Nations official Dr. Ralph Bunche declined the invitation to sign the appeal, both stating that their positions prevented them from endorsing the document, but that they would nonetheless do everything in their power to promote a settlement or cease-fire.

The appeal was published in news outlets around the world, from Pravda in Russia to the L.A. Times in the United States. It read:

The war in Vietnam challenges the conscience of the world. None of us can read day after day the reports of the killing, the maiming, and the burning without calling for this inhumanity to end. Our present object is not to apportion blame among the groups of combatants. The one imperative is that this crime against all that is civilized in the family of man shall cease.

Peace is possible. Both sides say that they accept the essentials of the Geneva Agreement. Then why not meet to seek a political settlement? Why not an immediate cease-fire?

In the name of our common humanity, we, the under-signed recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize, appeal to all the Governments and parties concerned to take immediate action to achieve a cease-fire and a negotiated settlement of this tragic conflict.

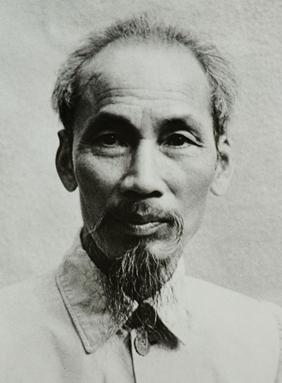

Ho Chi Minh, 1946.

A keen observer of world politics, Pauling had been following the situation in Vietnam as it had developed. Importantly, he was aware of Vietnam’s tumultuous political history, which is crucial to understanding how the Vietnam War came to pass.

Formerly part of the French colony of Indo-China, which included most of modern Cambodia and Laos, Vietnam came under the control of Japan in September 1940. This in turn sparked the rise of the Viet Minh, an army led by a Communist revolutionary figure, Ho Chi Minh. By August 1945, Emperor Bao Dai – who had been elevated into power by the Japanese – voluntarily abdicated the throne, paving the way for the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) in North Vietnam and a declaration of Vietnamese independence from both Japan and France.

Of particular interest to Pauling was the notion that, contrary to contemporary portrayals in the American media, the DRV seemed at its inception to be anything but totalitarian. On the same token, the DRV did not appear to be entirely communist. Rather, the DRV established a constitution which required at least a 25% voter turnout to legitimate results, and which gave all Vietnamese over the age of 18 the right to vote. In 1946, the areas controlled by the DRV hosted elections with a participation rate later determined to be 89%. The result of these ballots was a split cabinet, with the Communist-Workers’ Party occupying just over half of the governing body.

With war in Europe ended, however, France reasserted its influence over the northern half of Vietnam – the area now controlled by the independent DRV. In an effort to neutralize President Ho Chi Minh’s influence on the population, France supported the return to power of Emperor Bao Dai and created the State of Vietnam in the south as part of a “unified” Vietnam that included the neighboring kingdoms of Laos and Cambodia. Ruling from Saigon, this French-sanctioned state was anti-communist and perceived by the north as a representing a return to colonial control.

The State of Vietnam was granted independence from France in 1949, legitimizing it in the eyes of the world as the official government of all of Vietnam. By 1950, American military advisors had arrived in Saigon to provide the State of Vietnam with support. Meanwhile, the communist north was backed by the Peoples’ Republic of China and, to a lesser extent, by the Soviet Union. Hostilities ensued and, over the course of four years of fighting, the Viet Minh gradually regained and cemented control over the northern half of the modern state of Vietnam. In 1954, a series of agreements called the Geneva Accords ended the armed conflict between north and south. Although the French then evacuated the State of Vietnam, the would-be nation remained divided.

Ngo Dinh Diem

The Geneva Accords stated that nationwide elections were to be held in 1956 – by the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north and by the State of Vietnam in the south – on the specific issue of unification under a common government. This mandate for elections proved to be a crucial issue for Linus Pauling and others who questioned the legitimacy of American involvement in Vietnam, largely because the promised elections never took place.

Instead, the State of Vietnam in the south was dismantled and reorganized as the Republic of Vietnam in 1955. The republic’s new president, Ngo Dinh Diem, consolidated power quickly through a series of elections that were highly criticized and decried as fraudulent. Since the Republic of Vietnam was a new nation that had never agreed to the terms that had ended the previous war, the Diem regime announced that it would not participate in the Geneva-mandated elections to unify the country.

During this time, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) that was operating under Diem’s command was already receiving American financial support and working with U.S. advisors in their struggle against proponents of communism. The north Vietnamese government responded by initiating a campaign to unify with the south by force. Thus began the Second Indochina War, commonly known in the United States as the Vietnam War.

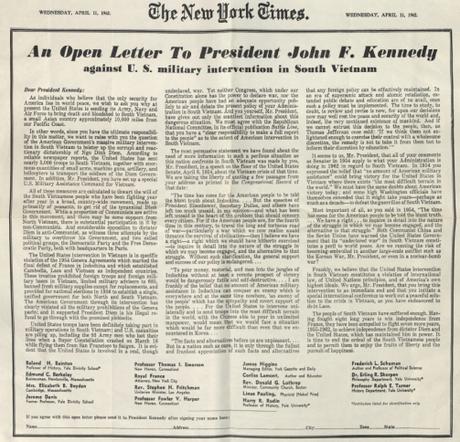

“An Open Letter to President John F. Kennedy Against U.S. Military Intervention in South Vietnam”, April 11, 1962.

Pauling had publicly pronounced his stance against military involvement in Vietnam as early as 1962. In that year, he signed an open letter to President Kennedy that was published in four major newspapers and included the endorsements of fifteen other eminent public figures and humanitarians. The letter expressed concern over Kennedy’s financial and military commitment to the preservation of capitalism in South Vietnam, a commitment that had been gradually increasing since 1954.

In deciding to involve itself militarily in the conflict, U.S. officials claimed that violence against the Diem regime in the south was not the outgrowth of a local rebellion or civil war, but rather an invasion of military forces from the north seeking to oppress southern populations under the yoke of communism. From Pauling’s perspective, North Vietnamese military action and supply lines supported its forces in much the same way that the United States and France had previously supported the State of Vietnam and its antecedents in the south. However, it quickly became clear that it was a regional guerrilla force developing in the south, the National Liberation Front – known to Americans as the Viet Cong – that predominantly fought the war.

The presence of the Viet Cong lent a tension to Pauling’s judgement on whether or not American involvement was justifiable. On one hand, significant numbers of North Vietnamese infantry were not clearly or directly involved – this only came about years later following the onset of U.S. bombing raids in the north. However, it was also the case that the National Liberation Front (NLF) of South Vietnam had been created by the DRV as a tool for fomenting continuing communist revolutionary sympathies in the south. This occurred despite the fact that the army of the DRV, the Viet Minh, had been comprised of both communist and non-communist forces and that many of these non-communists had settled in the south following the independence of North Vietnam, but prior to later American relocation efforts. The extent to which the NLF constituted a foreign invading force as opposed to an externally organized command structure that served to coordinate a willing and local insurgency in South Vietnam would be the crux of the debate between Pauling and the Johnson administration in determining the way toward peace.

The complexities of the situation were not readily known to the American public in April 1962, when the Kennedy open letter was printed in The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Christian Science Monitor, and The New York Post. And so it was that, on the eve of his receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize, Linus Pauling was already attempting to bring what he believed to be an immoral and unconstitutional war to the forefront of the American consciousness.