[Concluding our series on Max Perutz, in commemoration of the Perutz centenary.]

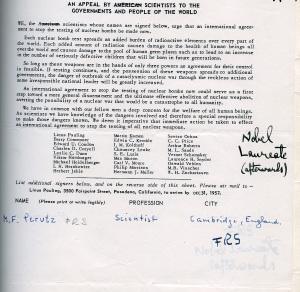

In 1957, Max Perutz and Linus Pauling wrote to each other again on a topic that was new to their correspondence. This time Pauling asked Perutz to sign his petition to stop nuclear weapons tests, a request to which Perutz agreed.

Signature of Max Perutz added to the United Nations Bomb Test Petition, 1957.

As the decade moved forward, the discovery of the double helical structure of DNA attracted ever more attention to the work of James Watson and Francis Crick. In May 1958, Perutz asked Pauling to sign a certificate nominating his colleagues Crick and John Kendrew to the Royal Society. Pauling agreed, though stipulated that Kendrew’s name be placed first on the nomination, as he expected that Crick would get more support. As with Pauling’s bomb test petition a year earlier, Perutz agreed.

At the beginning of 1960, William Lawrence Bragg wrote to Pauling about nominating Perutz, along with Kendrew, for the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics. Pauling was hesitant about the nomination, thinking it was still early, as their work on hemoglobin structure had only recently been published. Pauling also felt that Dorothy Hodgkin should be included for her work in protein crystallography. Bragg thought this a good idea and included Hodgkin in his nomination.

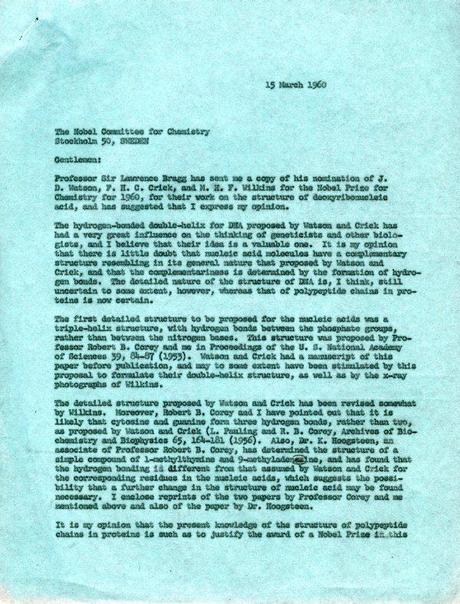

By March, Bragg’s nominations had gone through and Pauling was asked to supply his opinion. After spending some time thinking about the matter, Pauling wrote to the Nobel Committee that he thought that Robert B. Corey, who worked in Pauling’s lab, should be nominated along with Perutz and Kendrew for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry instead. Pauling felt that if Perutz and Kendrew were included in the award, Corey should be awarded half, with the other half being split between Perutz and Kendrew. Pauling also sent a letter to the Nobel Committee for Physics, indicating that he thought that Hodgkin, Perutz, and Kendrew should be nominated for the chemistry prize. Pauling sent a copy of this letter to Bragg as well.

Pauling’s letter to the Nobel Committee, March 15, 1960. pg. 1.

Pg. 2

In July, Bragg replied to Pauling that he was in a “quandary” about Corey, as he was “convinced that” Corey’s work “does not rank in the same category with that which Mrs. Hodgkin or Perutz and Kendrew have done.” Perutz and Kendrew’s efforts, he explained, had theoretical implications directly supporting Pauling’s own work, whereas Corey’s research was not that “different from other careful analyses of organic compounds.” Once everything was sorted out, Perutz and Kendrew were awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1962 (the same year that Watson and Crick, along with Maurice Wilkins, won in Physiology/Medicine, and Pauling, though belated for a year, won the Nobel Peace Prize) and Hodgkin received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1964. Robert Corey never was awarded a Nobel Prize.

Linus Pauling, Max Delbrück and Max Perutz at the American Chemical Society centennial meeting, New York. April 6, 1976.

Perutz and Pauling corresponded very little during the 1960s, with Perutz writing only to ask for Pauling’s signature, once for a photograph that would be displayed in his lab and a second time for a letter to Italian President Antonio Segri in support of scientists Domenico Marotta and Giordano Giacomello, who were under fire for suspected misuse of funds.

In 1971 Perutz read an interview with Pauling in the New Scientist which compelled him to engage Pauling on scientific questions once again. Perutz was surprised to have read that Pauling had tried to solve the structure of alpha keratin as early as 1937 and that his failure to do so led him to study amino acids. Perutz wrote that had he known this in 1950, he, Bragg and Kendrew might not have pursued their own inquiry into alpha keratin. Pauling responded that he thought his efforts had been well-known as he and Corey had made mention of them in several papers at the time. Pauling explained that he had difficulties with alpha keratin up until 1950, when he finally was able to show that the alpha helix best described its structure. Perutz replied that he was aware of Pauling and Corey’s work and the alpha helix, but was surprised that Pauling’s early failure to construct a model led him to a more systematic and fruitful line of research.

Perutz also wondered whether Pauling had seen his article in the previous New Scientist, which reflected on Pauling and Charles Coryell’s discovery of the effect of oxygenation on the magnetic qualities of hemoglobin. Perutz saw this as providing “the key to the understanding of the mechanism of haem-haem [heme-heme] interactions in haemoglobin.” Pauling responded that he had not seen Perutz’s article but would look for it, and also sent Perutz a 1951 paper on the topic. Perutz took it upon himself to send Pauling his own article from the New Scientist.

A few years later, in 1976, Perutz again headed to southern California to attend a celebration for Pauling’s 75th birthday, at which he nervously gave the after dinner speech to a gathering of 250 guests. Before going to the event in Santa Barbara, Perutz stopped in Riverside and visited the young university there, which impressed him. Perutz wrote to his family back in Cambridge that he wished that “Oxbridge college architects would come here to learn – but probably they wouldn’t notice the difference between their clumsy buildings and these graceful constructions.”

Perutz also visited the Paulings’ home outside Pasadena, which elicited more architectural comments. Perutz described to his family how the Pauling house was shaped like an amide group, “the wings being set at the exact angles of the chemical bonds that allowed him to predict the structure of the α-helix.” Perutz asked Pauling, perhaps tongue in cheek as he thought the design somewhat conceited, “why he missed the accompanying change in radius of the iron atom.” Pauling replied that he had not thought of it.

Bertrand Russell and Linus Pauling, London England. 1953.

In preparation for his speech, Perutz also took some time to read No More War! which he concluded was as relevant in 1976 as when it was first published in 1958. Perutz saw Pauling’s faith in human reason as reminiscent of Bertrand Russell’s. Indeed, the many similarities between the two were striking to Perutz, and he included many of them in his talk, “except for their common vanity which I discreetly omitted.” In a personal conversation, Perutz asked Pauling about his relationship with Russell which, as it turned out, was mostly concerned with their mutual actions against nuclear weapons. Perutz was somewhat disappointed that “they hardly touched upon the fundamental outlook which I believe they shared.”

Perutz and Pauling were again out of touch for several years until April 1987, when Pauling traveled to London to give a lecture at Imperial College as part of a centenary conference in honor of Erwin Schrödinger. Pauling’s contribution discussed his own work on antigen-antibody complexes during the 1930s and 1940s, during which he shared a drawing that he had made at the time. Perutz was in attendance and noticed how similar Pauling’s drawing was to then-recent models of the structure that had been borne out of contemporary x-ray crystallography. Perutz sent Pauling some slides so that he could judge the similarities for himself.

Flyer for Pauling’s 90th birthday tribute, California Institute of Technology, February 28, 1991.

The final time that Pauling and Perutz met in person was for Pauling’s ninetieth birthday celebration in 1991. Perutz, again, experienced stage fright as he gave his speech. But he was encouraged afterwards, especially after receiving a compliment from Francis Crick who, according to Perutz, was “not in the habit of paying compliments.” Perutz told his family that the nonagenarian Pauling “stole the show” by giving one speech at 9:00 AM on early work in crystallography and then another speech at 10:00 PM on his early years at Caltech. Perutz found it enviable that Pauling stood for both lectures and was still getting around very well, though he held on to the arm of those with whom he walked. Without coordinating, Perutz and Pauling also found a point of agreement in their talks, noting that current crystallographers were “so busy determining structures at the double” that they “have no time to think about them.” This rush often caused them to miss the most important aspects of the newly uncovered structures.

Just as Perutz first encountered Pauling through one of his books, The Nature of the Chemical Bond, so too would Pauling’s last encounter with Perutz be through a book, Perutz’s Is Science Necessary? Pauling received the volume in 1991 as a gift from his friends and colleagues Emile and Jane Zuckerkandl. Pauling’s limited marginalia reveal his interest in the text’s discussions of cancer and aging research. Aged 90 and facing his own cancer diagnosis, Pauling was particularly drawn to Perutz’s review of François Jacob’s The Possible and the Actual which sought, but did not find, a “death mechanism” in spawning salmon. Pauling likewise highlighted the book’s suggestion that “like other scientific fantasies…the Fountain of Youth probably does not belong to the world of the possible.” And Pauling made note of particular individuals that he had known well, like John D. Bernal and David Harker. Pauling deciphered the latter’s identity from Perutz’s less-than-favorable anonymous portrayal.

Pauling also noted spots where Perutz wrote about him. While most of these references were positive and focused on topics like Pauling’s influence on Watson and Crick and his breakthroughs on protein structure, one in particular was not. Perhaps less cryptic than the reference to Harker, Perutz described how “one great American chemist now believes that massive doses of vitamin C prolong the lives of cancer patients,” following it with “even more dangerous are physicians who believe in cancer cures.”

While critical, Perutz really meant the “great” in his comment and he continued to repeat it elsewhere. After Pauling passed away in August 1994, Perutz told his sister Lotte that “many feel that he [Pauling] was the greatest chemist of this century” while also being “instrumental in the protests that led to Kennedy and Macmillan’s conclusion of Atmospheric Test ban.” He reiterated this idea in the paragraph that concluded his obituary of Pauling, published in the October 1994 issue of Structural Biology.

Pauling’s fundamental contributions to chemistry cover a tremendous range, and their influence on generations of young chemists was enormous. In the years between 1930 and 1940 he helped to transform chemistry from a largely phenomenological subject to one based firmly on structure and quantum mechanical principles. In later years the valence bond and resonance theories which formed the theoretical backbone of Paulings work were supplemented by R. S. Mullikens’ molecular orbital theory, which provided a deeper understanding of chemical bonding….Nevertheless resonance and hybridization have remained part of the everyday vocabulary of chemists and are still used, for example, to explain the planarity of the peptide bond. Many of us regard Pauling as the greatest chemist of the century.