Daisaku Ikeda, 2010

[Part 1 of 2]

“If the people are not misled by false statements by politicians and authorities, they will recognize the need for world peace and their own responsibilities in achieving this goal.”

-Linus Pauling, 1988

In August 1945, Daisaku Ikeda, a resident of Tokyo and the son of a seaweed farmer, witnessed first-hand the devastation that two nuclear bombs wrought upon his homeland. The experience instilled in Ikeda an insatiable yearning to understand and eliminate the sources of war.

In pursuing this ambition, Ikeda studied political science at what is now Tokyo-Fuji University, and committed himself to the pacifist lifestyle of a Nichiren Buddhist. Ikeda’s chosen faith, named after a twelfth-century priest who emphasized the Lotus Sutra as the authoritative text for adherents of Buddhism, was becoming extremely popular among East Asians following World War II. Fundamental to the practice’s message was a strong call to treat others with respect and compassion, recognizing that all will become Buddhas in the end.

Ikeda also joined a new religious organization called the Soka Gakkai, which followed the teachings of Nichiren, and ultimately became the group’s president in 1960. In his capacity as chief executive, Ikeda focused intently on opening Japan’s relationship with China, and establishing the Soka education network of humanistic schools from kindergarten through university. He also began writing a book titled The Human Revolution.

As his tenure moved forward, the Soka Gakkai grew into an international network of communities dedicated to peace and to cultural and educational activities. In 1975, Ikeda founded an umbrella organization known as Soka Gakkai International (SGI) to fund, direct the resources of, and help facilitate communication between the dispersed Soka Gakkai members. In the 1980s, he turned his attentions toward anti-nuclear activism and citizen diplomacy, and it was in this capacity that he came into close contact with Linus Pauling.

Pauling’s first interaction with SGI came in the early 1980s, by which time the non-governmental organization was already actively cooperating with the United Nations’ department of public information to mobilize citizens for mass movements demanding peace. Seeking to increase SGI’s influence in propelling the peace movement, Ikeda decided to initiate communications with Pauling, who was by now splitting the majority of his time at the family ranch in Big Sur, California and the Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine in Palo Alto. It was at the latter location where Ikeda’s associate, Mr. Tomosaburo Hirano, would make contact with and interview Dr. Pauling.

This meeting proved to be the first step in a lengthy “courtship” that involved extensive correspondence between Pauling’s secretary, Dorothy Munro, and Ikeda’s assistant, Hirano. Indeed, more than six years would pass before Pauling communicated directly with Ikeda and, a bit later on, finally meet Ikeda in person.

Over the course of those six years, Hirano met with Pauling for two more interviews, focusing primarily on Pauling’s views on peace, but also, to a lesser degree, on his scientific work. Extracts from these sessions were often published in the Seikyo Simbun Press – the Soka Gakkai’s daily newspaper in Japan – for which Hirano served as associate editor. The pieces typically highlighted Pauling’s work toward nuclear disarmament and were often published in tandem with Ikeda’s release of new strategic proposals bearing titles such as “A New Proposal for Peace and Disarmament” and “Toward A Global Movement for a Lasting Peace.”

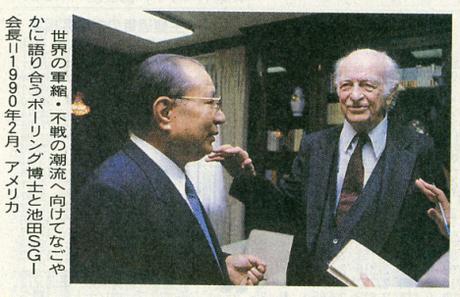

Pauling and Ikeda pictured together in an article published in the Kanagawa Shimbun newspaper, February 2005.

Finally, at the end of 1986, Pauling received a New Year’s card from Ikeda. The following year, during a trip to Los Angeles, Ikeda requested a personal meeting with Pauling, which Pauling obliged. Face to face at last, the two men developed an instant rapport with one another, quickly exhausting the allotted time for their meeting with discussion (aided by a translator) of a wide range of subjects: science, peace, childhood and adult life. The conversation even drifted into Pauling’s hobby of collecting and studying different editions of the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Ikeda was fascinated by Pauling’s warm recollections of major figures such as Albert Einstein, Albert Schweitzer, Bertrand Russell and, of course, Ava Helen Pauling, whose life and accomplishments Pauling cited as having been directly responsible for his peace activism. The two also talked about Pauling’s Nobel Peace Prize lecture, in which he had said that he believed the world had inevitably to move into a new period of peace and reason, that no great world war would again threaten the globe, and that problems should be solved by world law to benefit all nations and people.

In that same lecture, Pauling emphasized that, were it up to him, he would prefer to be remembered as the person who discovered the hybridization of bond orbitals, rather than through his work toward reducing nuclear testing and stimulating action to eliminate war. Nonetheless, Pauling considered the Nobel Peace Prize to be the highest honor that had ever received, in particular because of the onus that it placed upon him to continue that work. By contrast, Pauling felt that his Nobel Chemistry Prize, awarded in 1954, had plainly been earned for work already accomplished.

Over the course of their conversation, Ikeda also learned that being dedicated to peace, for Pauling, meant working toward the prevention of suffering for all human beings. In this, Pauling’s point of view as a humanist matched up well with Ikeda’s Buddhist philosophy. Specifically, Ikeda’s faith taught that one should regard others’ sufferings as their own and should seek out to eliminate it – a principle also expressed in the teachings of Christ, Kant’s Categorical Imperative, and in the Analects of Confucius, and more generally known as the Golden Rule.

Though Pauling was an avowed atheist, Ikeda pointed out that he did not feel his own religion to be an impediment to his rationality – the same rationality that Pauling believed guided his own desire for peace. Rather, Ikeda argued that

Religions must make every effort to avoid both bias and dogma. If they fail in this, they lose the ability to establish a sound humanism and can even distort human nature. The twenty-first century has no need of religions of this kind.

So concluded the long-awaited first meeting between two men of like interests. The communications and collaborations that were still to come will be explored in our next post.

Advertisements