It followed me home (c) Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

I sense a breakthrough on the horizon. I reflect that there must be few people who really attempt the transition from the new world to the old—few native English speakers make more than a half-hearted effort to learn another language; most find Europe quaint but of inferior living standards. In short, it seems more forward to have moved on from the old continent and its old-fashioned ways. The chasm between analytical and Continental philosophy is no mere physical border that one simply crosses by plane, but a dramatic shift in mindset, as I begin to experience first-hand at the Universität Wien.

In Vienna, there is an immense investment in and reverence of the history of philosophy, which is no real surprise given much foundational philosophy was written in German, and I immediately find myself thousands of years behind with my light smattering of Descartes and Plato, my utilitarianism and political theory, my if A then B. I expect history to be full of dry consecutive names; instead a rich forest of ideas towers before me, its immovable trunks mellow with age, its foliage swaying slowly and heavily, conscious of its own import. I tread slowly, leaf by leaf, dictionary in hand, eyes and mind open. In the face of my rigorous training, Deleuze and Guattari (1996: 22) assure me that philosophy ‘does not link propositions together,’ and caution against the false equivocation of philosophy and science that logic encourages. Paul de Man (1986: 19) politely suggests that I am under the tyranny of logic.

It is mildly amusing that the Anglo world holds so fast to the rigid linguistic frameworks they have built up around their ideas, precisely because of their clumsiness with language. Perhaps it is the very linguistic agility of Europeans—the ability to swing from language to language in a heartbeat, deftly expressing themselves in two, three, four or more languages without shyness or reserve—that makes them less precious about language. Language, indeed, is far from a monolith the way the monolingual tend to worship it. It bends and flexes under the demands of each moment; it changes flavor with each speaker, each a product of a unique mix of hereditary, educational and experiential backgrounds. Language is not God; it is an ever-mutating and stretching membrane that exists between individuals trying to make meaningful contact with one another.

My bewildered self, however, a strange (liquid) solution of (non-equal parts) English and German, confronts these wordplays with no small amount of confusion. De Man (1986: 16) wants me to ponder potentially but not definitively recasting the title of Keats’ The Fall of Hyperion in the genitive case, though my natural impulse is to think of titles as identifying handles that are a matter of convention, an afterthought to the real work, which is where we most probably ought to focus our attention. Deleuze wants me to remember a string of metaphors—meat, scaffold and cosmos—and to remember that ‘house’ and ‘scaffold’ are interchangeable, in a seemingly arbitrary game of free-association, but is fiercely insistent that other related words play absolutely no part here. That though the Greeks philosophised via dialogue, philosophers in fact run from discussion, and communication is decidedly irrelevant (Deleuze & Guattari, 1996: 28, 29). What am I to do with these sudden and pervasive contradictions, these unexpected associations and dissociations? Does this English word really capture that French word, and does German have a more precise distinction between reason and understanding, or a finer delineation of existence? Should many words and all their shades of meaning be available, since we all speak different tongues; or should we defer to the language that best picks out the thought we want to express?

Learning another language, of course, makes you take more notice of your own. For I remember being uninterested in the etymological background of the word ‘express,’ which I believe Dewey (1934) spends some time elaborating, to draw attention to the way we squeeze meaning out, or press the essence of our thoughts of feelings from our bodies. German, with particular crispness, makes me confront that I am engaged in a struggle of Ausdruck, of pressing out, which makes this whole enterprise of wringing out the language much more plausible. Perhaps we would do well to mince our words rather than pride ourselves on clarity—arrogantly hiding the duplicity of words behind a fragile screen of necessity.

My tentative steps into the cavernous history of philosophy lead me to concepts wholly unfamiliar to my Anglo ears: such as the apparently familiar trivium, the historical partitioning of language into its three sciences (de Man, 1986: 13). I start to suspect some sort of British intellectual imperialism that kept such pedagogical categories on the quiet on Anglo turf, all the while parading around to the beat of irrefutable, incontestable, unconquerable logic. The trivium, I belatedly learn, breaks language down into grammar, rhetoric and logic (all of which look more pleasing with k’s: Grammatik, Rhetorik und Logik), which exist in an uneasy tension. De Man (1986: 14) points out the ‘natural enough affinity’ between logic and grammar, and the discomfort that rhetoric tends to introduce to this delicate balance. Why resist (Continental) literary theory? Precisely because it resists your concept of language, but from within language itself. It reclaims the rhetorical aspect of language and brings it to center stage, instead of flicking it aside as unnecessary ‘ornament.’ Were language scientifically precise, we could find in it a solid epistemological foundation. And, as monolinguals, that is the understanding of language that we develop and nurture and protect. When the polylinguals arrive with their freewheeling interchangeability, with their ‘literariness,’ drenched in their clouds of loosely connected pretty words, our chests grow tight and our eyes narrow with suspicion.

Yet our common Greek heritage esteems this more seductive layer of language. ‘How did he entertain you?’ Socrates asks his friend Phaedrus. ‘Can I be wrong in supposing that Lysias gave you a feast of discourse?’ Plato (2010) reports the two stirring each other to higher and higher planes of ecstasy, enraptured in turn by the written speech prepared and recorded by the brilliant rhetorician Lysias, and by Socrates’ spontaneous responses on the theme of love. Having worked each other into a ‘phrenzy,’ they try to knuckle down just what this art of rhetoric is, and how it is to be mastered. Phraedus voices the concern that echoes across the millennia in the doubts of the logicians: ‘I have heard that he who would be an orator has nothing to do with true justice, but only with what is likely to be approved by the many who sit in judgment … and that from opinion comes persuasion, and not from the truth.’ Socrates imagines Rhetoric herself reproaching such Spartans: ‘Mere knowledge of the truth will not give you the art of persuasion.’ Certainly, those who cling fast to grammar and logic suspect this ‘art of enchanting the mind by arguments’ of being ‘a mere routine and trick, not an art.’

Plato’s meta-story concludes with the observation that souls come in all kinds, and must be persuaded on their own terms; a good rhetorician, then, does not pound him with a stick of logic but learns to systematise and recognize types and have her method of argument polished and at the ready. ‘He who knows all this, and who knows also when he should speak and when he should refrain, and when he should use pithy sayings, pathetic appeals, sensational effects, and all the other modes of speech which he has learned’ is a skillful practitioner of the art.

While we risk dullness and lifelessness in delivery if we place all our confidence in the irrefutability of technical correctness (de Man, 1986: 19), clear and logical expression certainly need not be so dry. The elegant and amiable writing of David Hume attests to this, and I recall the deep impression he had on my friend and philosopher colleague Mark Hooper, and in turn on me. In Hooper’s reading of Hume it suddenly struck him that all writing could be beautiful, that one must simply apply a little thought and make a concentrated effort to construct a tight, meaningful and pleasing sentence. ‘Why are there bad sentences?’ Hooper demanded to know, though probably putting it more elegantly. The sentiment has remained with me, and propelled my own writing, which I have always seen as more than a vehicle for ideas. I relish the deftness and precision with which one can summon words, with a little care, the poetry that one can extract from them—ever trembling at the brink of pretentiousness but never (intentionally) sacrificing clarity. Hume’s Scottish pride drove him to France rather than to England, and the example of this self-professed cosmopolitan glows warmly in my mind.

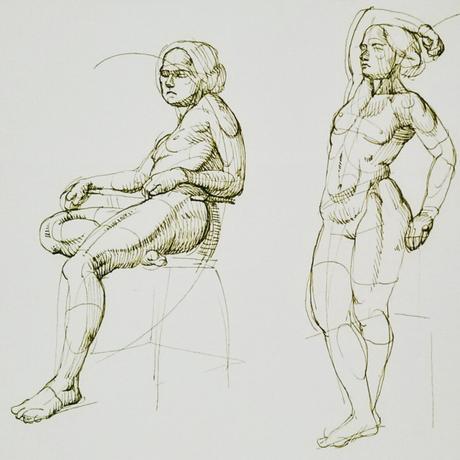

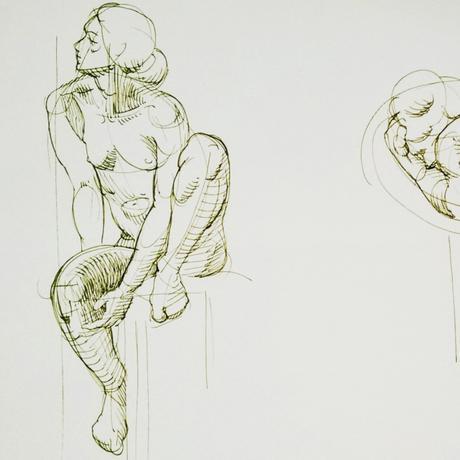

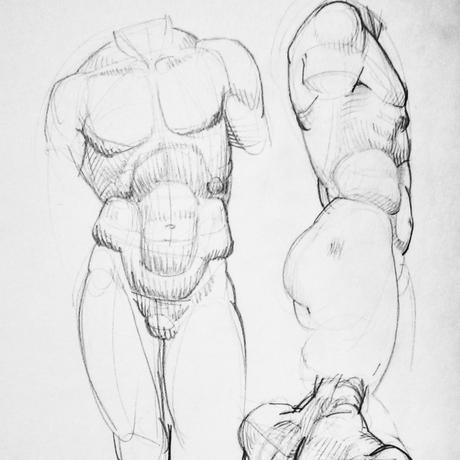

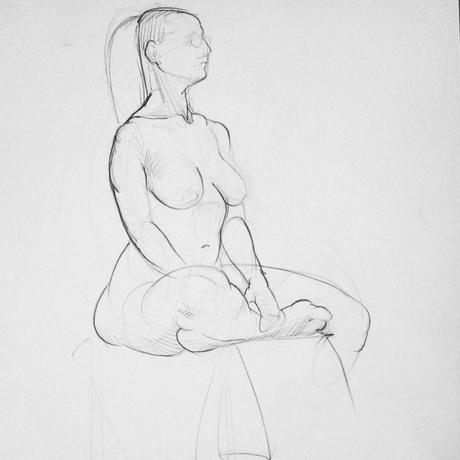

When I began to seriously study drawing, I took a brief but intense string of classes with the formidable David Paulson. He was renowned for breaking pencils and students. He broke my pencil, and my brain, but his intensity stirred my spirit rather than broke it. Yet I left his class feeling utterly adrift. My lines became cruder, more abrasive. I tread hesitantly, my lines faltered. But with time I regained my composure and drew with greater vigour, more poetically, finding expression in bold, calligraphic lines that cut deep into the page. Paulson barks at me still, from the back of my mind. He left an indelible impression on me as a draughtsperson, he left a trace of his marks in mine.

And so it must be with philosophy. When we confront that ancient, disconcerting, but compelling, thickly-grown forest, when we meet with something that seems to tap some deep source just beyond our reach, the important thing is to keep on pushing. To latch on to the people who can guide us through this unfamiliar territory, and to relish the feeling of being cracked open and pieced back together in a new way. That’s what life does with us anyway, and there’s nothing for it but to go on.

De Man, Paul. 1986. The Resistance to Theory. Vol. 33. Theory and History of Literature. Manchester: Manchester University.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1996. What Is Philosophy? Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell. New York: Columbia University.

Dewey, John. 1934. Art as experience. Minton, Malch & Company: New York.

Plato, and Benjamin Jowett. 2010. Plato’s Phaedrus. 2.0.0 edition. Actonian Press.