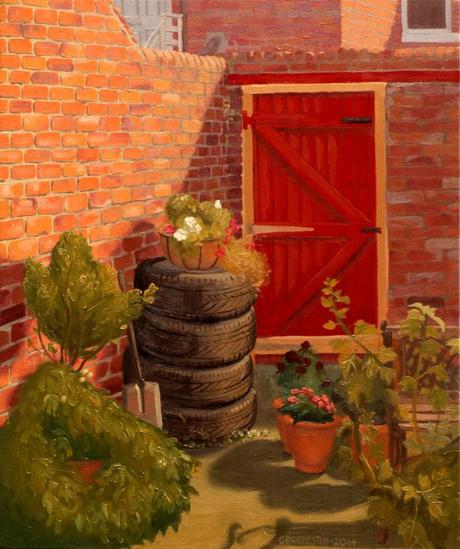

Lavender Gardens © Samantha Groenestyn; oil on canvas

I lately find myself floating untethered across Europe, of unfixed address and relying on the kindness of friends. Determined to do away with distractions, excess possessions, and non-painting-related ambitions, my faithful and scuffed old suitcase and I have somewhat conspicuously fallen off the path of respectability.

Making big wishes, Vienna

Wafting from city to city, from house to house, welcomed warmly into the homes of friends, I’m permitted into the private spheres of young doctors, paramedics, physicists, engineers and environmental charity workers, and granted a sobering insight into the contrasts in our chosen careers. But I’m also freshly awoken to how difficult it is for each of us to forge our way. My friends are well-travelled, well-educated, some are employed, some have suspended employment for the sake of a relationship, some have worked offshore, some are physically overworked, others are mentally under-challenged, some need to secure funding to guarantee their own ongoing employment. Those of us with money are not necessarily respected, because their jobs are too physical or not demanding enough of their time. Those of us who are working for the betterment of the world are anxious at not contributing enough. And I, as capable as they, cling resolutely to my cause in the face of my meagre earning-power.

Married to the sea, my all time favourite web-comic

This unsettling confrontation with earning ability has been somewhat tempered by some thoughts from philosopher Alain de Botton. I found his book Status anxiety on a bookshelf in a new home and read it hungrily and hopefully. For at heart, we all want to occupy ourselves with something which challenges and satisfies us, and we want others to respect us for our efforts. But are our equations, prescriptions, policies and drawings enough when the measure held against our work is money? De Botton lays out an historical account of our attitude to wealth that can at least reassure the financially-challenged that they are not necessarily worthless. He describes the complete historical about-face of our estimation of wealth, and, most strikingly, its connection with virtue.

Poverty wasn’t always such a psychological burden to bear, argues de Botton (2004: 67-68), particularly in a world where one was born either into nobility or peasantry according to God’s will. One’s moral worth could not be wrapped up in one’s social standing if that immutable standing was allotted by God. Poverty might bring physical discomforts, but not shame. And since the aristocracy acknowledged that their luxuries were only made possible through the untiring efforts of the lower classes, it was only fitting that they demonstrated charity and pity toward these unfortunates. A delicate balance of interdependency between rich and poor reinforced the idea that virtue and moral worth were not reflected in wealth (2004: 70).

But in about the middle of the eighteenth century, argues de Botton (2004: 75-76), some hopeful meritocratic ideas began to take root and to dismantle these beliefs and thus to erode our collective appraisal of poverty. And, more sinisterly, supply and demand were switched. Rather than considering the role of the poor a necessary evil, fatefully bestowed, their position came to be described as dependent on the whims of the rich. Without demand, their labour would be for naught. Thinkers as forceful as David Hume and Adam Smith helped to redefine who depended on whom (2004: 76-78):

Hume loving, Edinburgh

‘In a nation where there is no demand for superfluities, men sink into indolence, lose all enjoyment of life, and are useless to the public, which cannot maintain or support its fleets and armies.’ (David Hume, 1752).

National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh

‘In spite of their natural selfishness and rapacity, though they mean only their own convenience, though the sole end which they propose from the labours of all the thousands whom they employ be the gratification of their own vain and insatiable desires, the rich divide with the poor the produce of all their improvements. They are led by an invisible hand to make nearly the same distribution of the necessities of life, which would have been made, had the earth been divided into equal portions among all its inhabitants, and thus, without intending it, without knowing it, advance the interest of society, and afford means to the multiplication of the species.’ (Adam Smith, 1776).

Adam Smith, Edinburgh

Charity became a burden; the poor became a nuisance (2004: 78). Coupled with progressive ideas that every individual ought to be rewarded according to his or her abilities and achievements, the modern attitude to poverty is one of disdain. For the flipside of meritocracy is that those who do not excel deserve the hardships and stigma that they have thus earned. It seems a regrettable but inevitable price to pay. Since one ought to be able to improve one’s position, failure to do so has come to imply moral failure in a way it did not in the past (2004: 87). De Botton (p. 85) explains, ‘An increasing faith in a reliable connection between merit and worldly position in turn endowed money with a new moral quality.’ And, worse: ‘To the injury of poverty, a meritocratic system now added the insult of shame’ (2004: 91).

De Botton goes on to explore antidotes to this new state of affairs, a string of themes that reads like my biography: Christianity, Politics, Philosophy, Art and Bohemia. Perhaps my attraction to these things has lessened my own regard for money and for the esteem that comes hand in hand with it. At heart, his message is to seek value elsewhere; define worth on your own terms, as many have before. Build, adopt or steal an unshakable moral code so that in dark times you can measure your life and your own worth against this and not money; so that you can respect yourself and stay focused on your life’s work. Perhaps that confidence and determination is enough win the respect of those who doubt you.

De Botton, Alain. 2004. Status anxiety. Hamish Hamilton: London.