Our family originally evolved in Africa, but over the last 2 million years we’ve spread throughout the world in a series of migrations. Dmanisi in Georgia (the country, not the state) is one of the oldest hominin sites outside of Africa; dating to around 1.78 million years ago so it provides critical information on what the first of these migrants – called Homo erectus - was like1.

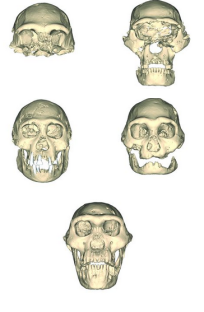

The skulls from Dmanisi. D4500 is the bottom one.

4 skeletons have already been discovered at Dmanisi and they’ve revealed that these early pioneers were surprisingly primitive; considering what they accomplished. They lacked the adaptable handaxes of later species and had very small brains, only slightly bigger than chimpanzees (600 – 700 cc, compared to the 450 cc of chimps)1. At the same time they were capable of adapting to the new plans and animals they encountered2 and they also cared for their elderly. This raises all sorts of interesting questions over just how important big brains and advanced tools are.

Earlier this month information on a 5th skeleton (consisting of a complete skull with jaw bone and possibly a few bones from the rest of the body) from Dmanisi was published, providing even more information on the first of our family to leave Africa. However, this discovery also has far reaching implications for the rest of human evolution.

The new skull, known as D4500, was discovered in the same spot as the earlier finds so is most likely part of the same group. However, it is quite different from the first four skeletons, with a much smaller brain (546 cc vs 600 – 700 cc) and a large projecting face. This shows that Homo erectus was a lot more variable than we first thought, changing how we should define the species3.

As the first migrants left Africa and spread throughout the world the populations in different regions began to change. Since these regional variants were first discovered in the 19th century there has been extensive debate over whether or not they were different enough to be defined as a new a species, or should all be labelled Homo erectus4. In fact when the Dmanisi skeletons were first discovered some wanted to call them Homo georgicus for this very reason.

The classic human family tree, with some of the species that may be removed by this find crossed off

By showing that Homo erectus was very variable, D4500 definitively proves that these regional variants are not distinct species, but fall within the range of Homo erectus. Further, Homo erectus isn’t the only species with “variants” that have been debated. The earlier Homo habilis (thought by some to the ancestor of Homo erectus) has a more robust version, thought by many to be a distinct species called Homo rudolfensis.

Since this new skull suggests hominin species are actually more variable, rudolfensis and habilis may have to be be re-classified as a single species. In fact, D4500 shows that Homo habilis may even fall within the variation of Homo erectus3! However, this conclusion is strongly contested by other scientists as there is more variation within Homo habilis/rudolfensis than found at Dmanisi.

Still, many human species may be removed. All in all, this trimming of the human family tree may remove at least 4 different species; possibly grouping them into Homo erectus.

However, given that D4500 is so different from other skulls found at Dmanisi some may wonder whether it is even Homo erectus, challenging this redefinition. However, not only was D4500 found in close association with the other skulls but some bones from the body were also found. These show that the rest of the skeleton was much more like the Homo erectus we’re used to. It should also be remembered that the variation now documented within Homo erectus is no more extreme than the variation seen in modern chimps or humans3!

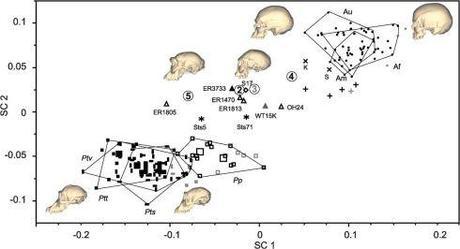

A comparison of chimps, humans and fossil humans. Chimps are squares, humans circles and the numbers are the Dmanisi skulls. Note how the variation between chimps is no greater than the variation in the Dmanisi skeletons

This is a major change to our understanding of human evolution so has understandably been picked up by the popular press. They’ve run with headlines like “Skull of Homo erectus throws story of human evolution into disarray” (from the Guardian) or “Does this skull rewrite the history of mankind?” (from the Daily Mail). However, the “story” of human evolution remains unchanged. We evolved in Africa and migrated out. All this discovery does is change the labels a bit which – whilst significant – is hardly the “disarray” that some of the more extreme headlines suggest.

D4500 shows that single species of human are more variable than we thought. which means we have to trim our family tree; reclassifying some groups previously thought to be distinct species. At the very least, this will make it easier to learn the names of all of our ancestors!

References

- Gabunia, L., Vekua, A., Lordkipanidze, D., Swisher, C. C., Ferring, R., Justus, A., … & Mouskhelishvili, A. (2000). Earliest Pleistocene hominid cranial remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: taxonomy, geological setting, and age. Science, 288(5468), 1019-1025.

- Messager, E., Lordkipanidze, D., Kvavadze, E., Ferring, C. R., & Voinchet, P. (2010). Palaeoenvironmental reconstruction of Dmanisi site (Georgia) based on palaeobotanical data. Quaternary International, 223, 20-27.

- Lordkipanidze, D., de León, M. S. P., Margvelashvili, A., Rak, Y., Rightmire, G. P., Vekua, A., & Zollikofer, C. P. (2013). A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo. Science, 342(6156), 326-331.

- Boyd, R., Silk, J. B., Walker, P. L., & Hagen, E. H. (2000). How humans evolved (Vol. 8). New York: WW Norton.