When I first sleep with someone we have to have the talk: “You really wear one of those?” It can be a bit embarrassing to sleep with an eye mask and earplugs, but what am I supposed to do? I’m bad at sleeping.

Sleep is important, obviously for feeling rested and awake during the day, but also for maintaining health. Disruptions to sleep increase the risk of not just mental illnesses like depression but also infectious diseases, heart disease, and cancer.

Modified version of Alex Gray’s Insomnia

Growing Up In Insomnia

Insomnia is a surreal, solitary, silent world I find myself in while the rest of the world slept. I’ve been visiting it as long as I can remember: lying in bed, feeling exhaustion behind my eyes, but my thoughts tumbling with such force that I knew they wouldn’t slow down anytime soon, and I was stuck in insomnia.

Long before my high school days of sneaking out of the house I’d already learned which squeaky steps to skip over to avoid waking my parents. I’d creep downstairs, microwave a glass of milk, and hunker down in front of late-night infomercial hell.

By high school I was dabbling in drugs: melatonin, valerian root—Oh god, I can remember the heartburn and awful herbal taste of valerian root burps. I’d use them nights I knew I wouldn’t be getting much sleep–before the first day of school, a cross-country race, or going camping. They weren’t necessarily events I was nervous or even excited about; even just the anticipation of novelty was (and still is) enough to keep me up.

College presented its own set of problems—for example a freshman roommate with a penchant for getting up early, eating a bowl of cereal, and dragging his metal spoon along the edges of his porcelain bowl to get every last flake. I started wearing earplugs.

A Cup of Ambition

College is also where I discovered the drug that’s a godsend for an insomniac—coffee. What? I can actually focus in a 9am class? But it’s a god-sent double-edged sword. Too much and I’ll be up all night in limbo: too wired to sleep, but too tired to do anything.

I’ve since found out through 23&Me, that my body breaks down caffeine slower than most people’s.

I have to copies of the ‘C’ genetic variant affecting my liver enzyme, CYP1A2, which breaks down caffeine (and other substances). This variant means my copies of this enzyme likely work slower than 85% of other people’s enzymes. While these variant enzymes work at normal speeds in baseline conditions, their activity isn’t increased as much through daily coffee consumption.

So for people with either variant who have never drunk caffeine, their response to caffeine will be similar. But when most people drink coffee daily, those with the ‘A’ allele will quickly become ‘metabolically’ or ‘pharmokinetically’ tolerant to it because their liver is breaking down more of the caffeine before it reaches the brain. However, people like me with the ‘C’ allele enzyme won’t develop as much of this metabolic tolerance. In fact people like me with two ‘C’s have an increased risk of getting heart attacks if we drink a few coffees a day, whereas people with the ‘A’ allele don’t seem to have this risk. (But on the bright side we’re cheap coffee dates..?)

Tangent – is caffeine addictive?

I’ve always envious of people who can drink a coffee at night and then fall asleep. “I’m addicted to coffee,” these people often say as an explanation.

It’s controversial whether coffee is addictive, but I have a strong opinion. People can definitely build a tolerance to it and even experience withdrawal symptoms like a headache in the morning if they don’t drink it. Therefore, you might say they’ve grown physically dependent and tolerant to caffeine. Does that make them addicted?

To decide let’s look at heart medicine. People may need to up their dose over time to keep their heart rate low (because of tolerance), and if they suddenly stop taking that medicine, their heart rate will speed up to the extent it could even cause a heart attack or kill them (because of withdrawal). However, would you say these people are addicted to their heart medication? I don’t think this parallels how we think about addictive drugs—no one is getting their kicks off of heart medication.

On the other hand, many people—myself included—love their coffee. One of caffeine’s molecular targets is an adenosine receptor, which is highly enriched in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), an important component of the neural reward circuitry, which all addictive drugs target.

I once saw Eric Nestler—this guy literally wrote the textbook on how drugs affect the brain—give a talk on addiction and he mentioned that he didn’t think caffeine was addictive according to the definition doctors use. The clinical definition of addiction is “a chronic, relapsing brain disease that is characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use, despite harmful consequences.” Nestler said he had never heard of people compulsively using caffeine despite harmful consequences.

Here I’ll be bold enough to disagree with the textbook-writing superstar scholar. For a year in medical school I shadowed a cardiology clinic, and met more than one little-old southern lady, who refused to give up their coffee (or even switch to decaf) despite their cardiologist telling them the caffeine was dangerous for their heart. They were so vehement about it that they wouldn’t even just lie to their doctor and drink it behind his back. “I need my coffee,” they’d say. That’s what a coffee addict looks like.

My Visit to the Sleep Doctor: The Pulmonologist?

In graduate school I finally visited a doctor about my sleep. Maybe because the stress of grad school was making it worse, or maybe because I had learned enough about the medical system to realize that if this was a problem that was bothering me, I had to take action myself and seek out care. I was tired, for example, of worrying about sleeping the night before the exam more than worrying about the exam itself, or, when excitement had kept me up, yawning through what should have been the most amazing days of my life.

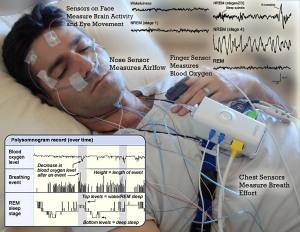

But perhaps the real reason I had put off going to a sleep doctor was that I worried it would shatter a long-running fantasy. In my imagination, I would go and the doctor and describe my sleep problems, and he or she would listen, concerned and tell me to come back for a sleep study. In the hospital laboratory, with my head covered in electrodes and wires, I would of course struggle to fall asleep, and my brain would generate signals indicating some treatable disease. After treatment my sleep problems would go away, along with the mental fogginess and I’d realize the feelings I had mistaken for forgetfulness or laziness were really just symptoms of my sleep disorder. Freed from this burden, I would become the prolific, productive person I always dreamed I could be.

So yeah, you could say I went in to my appointment with unreasonable expectations.

The experience was actually kind of a crazy. The doctor I was referred to I had met before. He had lectured me in med school, and rumor had it he was the son of the real life Doc Hollywood (he has the same name but Wikipedia says otherwise).

But, that’s not even the crazy part. What’s crazy is my sleep doctor was a pulmonologist—that’s right a lung doctor. Not a brain doctor, a lung doctor.

Actually it turns out it’s quite common for pulmonologists to become sleep specialists because one of the most common sleep problems in the United States (where obesity is rampant) is sleep apnea. In sleep apnea, patients stop breathing in the middle of the night disrupting their sleep. They may fall immediately back to sleep and be unaware of the problem, unless a partner witnesses them gasping for breath in the middle of the night, but these short awakenings disrupt the complex, patterned architecture of sleep. (If you snore in the night and experience excessive daytime sleepiness, you should probably get yourself checked out.) Because pulmonologists are well trained in breathing-conditions, they can get certified as sleep specialists in half the time of other medical specialists like psychiatrists and neurologists.

The Appointment

After filling out a survey about my normal sleep experiences, I met with the doctor. I learned my situation is pretty normal. Lots of people deal with insomnia and there’s little we can do about it. One completely sleepless night per month is in the range of normal, the doctor explained, though he was a bit concerned I was reporting two a month with difficulty falling asleep other nights.

I told him I have a lot of difficulty falling asleep at night, but usually then will really struggle with getting up in the morning. He said these are signs of a delayed or abnormally long body clock. Because of my altered circadian rhythm, he said I should take special care to avoid drinking coffee past noon and bright lights, particularly blue light, after dark. Blue light disrupts the body’s circadian rhythm, as the brain mistakes it for daylight. He noted that while delayed circadian rhythms are correlated with higher IQs, they are also correlated with people doing worse in school and at their jobs.

Source: Luke Mastin

Circadian Rhythm Aside

Most life maintains a 24-hour or circadian rhythm: animals, plants, fungi, and even some bacteria. The entire human body maintains a circadian rhythm, which presents a problem—how do cells stay aligned with one another and with the world? In charge of keeping the entire body aligned with world is the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus (SCN)[1], a brain area in the hypothalamus. The SCN receives direct projections from a specialized photodetector in the retina which is sensitive to blue light—the intrinsically photosensitive Retinal Ganglia Cell (ipRGC)

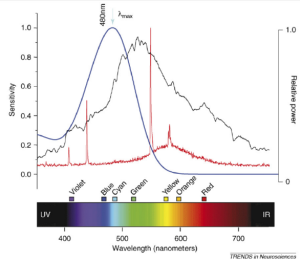

Blue: Action spectroscopy shows the melonopsin photopigment contained in retinal ganglion photodetectors is maximally sensitive to 480nm blue light, somewhat sensitive to green light and violet light, but largely unaffected by yellow, orange, and red light.

Black and Red: For comparison, the spectrum admitted by traditional incandescent lightbulbs (black) and fluorescent light bulbs (red). Note these graphs are all normalized to the wavelength with the maximum intensity set to one.

Source: Hankins, et al. 2007.

Source: http://thebrain.mcgill.ca/flash/a/a_11/a_11_cr/a_11_cr_hor/a_11_cr_hor.html

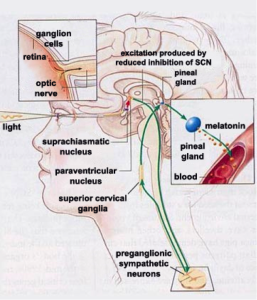

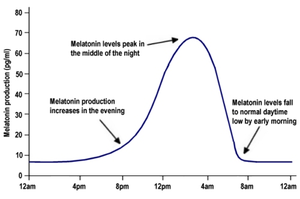

The blue light signals detected by the ipRGCs are converted into electric signals, and transmitted directly to the SCN. The SCN contains inhibitory neurons which project to another region of the hypothalamus, the periventricular nucleus. So in the presence of blue lights the SCN will be activated and inhibit the Paraventricular nucleus, blocking signaling further down this pathway. However, in the absence of blue light, the SCN isn’t activated so it doesn’t inhibit the paraventricular nucleus, freeing it to signal down to sympathetic neurons in the spinal cord. This neurons which signal back up through the superior cervical ganglia back into the brain, where they stimulate the pineal gland to release melatonin, a sleep-producing hormone, into the bloodstream where it can act on the brain and body to signal it is night and time for sleep.

I liked the doctor’s advice on light, but it wasn’t new. I’d already been trying to cut down on the blue light at night, using F.lux on my laptop, and Twilight for my android phone. I’d even gone so far as to buy glasses that filter out blue light.

(The glasses turned out to be fun to mess around with (did you know asphalt roads are full of pink?), so I ended up buying a bunch of different colors for fun–I’m a nerd, don’t judge me. There are also hip versions if you want to go out with them and don’t want to look like a mad scientist, but are okay with being that dude wearing sunglasses at night.)

For me, the doctor also recommended taking melatonin every night. While in high school I had taken it occasionally to help with days I felt sleep was particularly important and I was unlikely to get it. However, the doctor told me it’s more effective when it’s taken daily and consistently. Instead of thinking about it as a sleep inducer, it’s better to think more as a way to shift and normalize your circadian rhythm over time. Similarly, he recommended using a light box in the morning or trying to get some sunlight early. (On this note I wonder if my eye-mask is delays the light signals in the morning and may actually actually a bit counter-productive.)

On especially tough nights he recommended taking Benadryl, generic name diphenhydramine, for it’s drowsy side-effects. First-generation anti-histamines like Benadryl easily cross into the brain from the blood stream where it can block histamine receptors. Interestingly, while we tend to associate histamine with its peripheral involvement in allergies, histamine also acts as a neurotransmitter, and histamine releasing neurons are the neurons in the brain that correlate the most with wakefulness.

Using these drugs cold potentially cause dependency, but they are not thought to be addictive. (These are concepts I discussed above in the tangent about caffeine and addiction.) I did worry that potentially taking melatonin chronically could diminish my pineal’s ability to naturally produce it. This phenomenon is seen with other hormones, for example this is why taking anabolic steroids can shrink the testicles. While the doctor couldn’t speak to that specifically, he said he had patients who had been taking it for decades and none of them had ever complained about side effects. Practically, maybe you’ll have to take it for the rest of your life, but it’s over the counter, cheap, with few known side effects. There are some side effects including headaches, depression, and (ironically) daytime sleepiness. Hopefully this goes without saying, but you should talk with your doctor before starting any new drug or supplement. Even the light boxes have been associated with exacerbating mania in people with bipolar disorder.

Generally, the evidence shows that for people suffering from insomnia, doctors should first check for another condition which may be exacerbating the problem: psychiatric illness, substance abuse, a specific sleep disorder, or side effect of a medical condition.

Patients should practice proper sleep hygiene: try to sleep and wake at consistent times; avoid doing work in their bedroom; if in bed for more than 30 minutes without sleep, get up and do something until you feel tired; avoid bright lights, exercise, meals, nicotine or caffeine shortly before bed; try to control stress and practice intentional relaxation; try to exercise regularly; avoid daytime naps longer than 20-30 minutes. Further behavioral interventions like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia and Sleep Restriction Therapy have also been shown to be effective. A number of drugs have been shown to be effective, though excluding melatonin these are normally only prescribed in extreme cases. These drugs include certain classes of anti-depressants, sedatives, and the newly FDA-approved orexin antagonists.

Conclusions

Going to the doctor didn’t give me any silver insomnia-slaying bullets or unlock any super-human abilities, but I think it has helped a bit. Like many chronic conditions it has its ups and downs: I go through phases where I sleep pretty normally, and others where it seems a nightly problem, maybe because of the twisted joke of psychogenic insomnia, where worrying about not sleeping make it harder for your brain to transition into sleep.

For me, the most effective way to get to sleep actually goes against many doctors’ recommendations to not do anything in your bed other than sleep. It’s actually my mom’s perennial advice and the habit I had as a child: reading to fall to sleep.

I’ll read and gradually turn down the knob on my halogen lamp, and when I notice I’ve lost my place on the page, or find myself blinking my eyes to stay awake, that’s when I lay the book down,

twist the light all the way off,

pull the eye-mask down over my eyes, the sheet up to my neck,

and I visit a world infinitely more pleasurable than insomnia—sleep.

———–

[1] The Suprachiasmatic Nucleus jargon broken down: It’s an area of the brain (or nucleus—different meaning of nucleus from the one where DNA is stored, fucking biologists) that lies on top of (or supra) the optic chiasm (chiasmatic), which is another part of the brain where the two optic nerves cross over one another and for an x-shape (like the greek letter chi).

———–

If you liked this article, please share or follow the blog to see more like it. I do this to share my love of neuroscience and psychology but also because of an insatiable need for the approval of strangers, so help me out!