{[. . .] That hard closed cone, which defied all violent attempts to open it and could only be cut open with a knife, has thus yielded to the gentle persuasion of warmth and dryness. The expanding of the pine cones—that, too, is a season. —Henry David Thoreau, Wild Fruits}

‹31 October. Last spring somebody brought home a handsome pitch-pine cone, which had freshly fallen and was closed perfectly tight. (Squirrels always love stripping some pitch-pine cones.) It was put into a table drawer. I was greatly surprised to find that it dried there and opened with perfect regularity, filling the drawer; and from a solid, narrow, and sharp cone has become a broad, rounded, open one—has in fact expanded with all the regularity of a flower’s petals into a conical flower of rigid scales and has shed a remarkable quantity of delicate winged seeds.

Pitch-pine cones are very beautiful—not only the fresh leather-colored ones, but especially the dead grey, covered with lichens, the scales so regular and close, like an impenetrable coat of mail. These are very handsome to my eye. Also these which have long since opened regularly and shed their seeds. Such seeds and scales are both elaborately and perfectly constructed, and remind me of teams that insist on playing a version or another of diamond midfield—certainly unripe (when little over a year old) but concealing, perhaps, some of the most thrifty twigs—like, for instance, AC Milan. Every embodiment of the Milanese squad, under Massimiliano Allegri, has invariably looked like a pitch-pine cone. The shape is prepared with a promiscuous farmer’s knack.

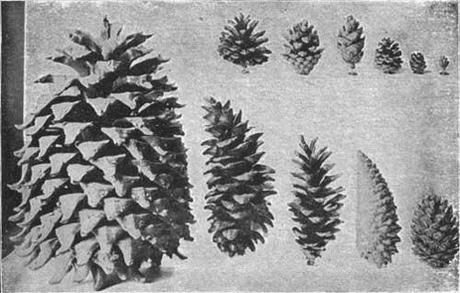

Like corn reapers in a Devonshire parish, Allegri’s starting XI enter the pitch for a point-hunting session rejoicing and chanting to the goddess Ceres. From right to left, Milan’s midfield pitch-pine cone is narrow, solid, and impenetrable to pressing; or else, each scale comes armed with a spine of various age (Gattuso and Ambrosini being the rye from the oldest barrels, Nocerino and Van Bommel somewhat younger bushels), as if to protect its seed from squirrels and birds. In the worst circumstances, as in September against Fiorentina, Milan’s pine-cone grows according to a flat and predictable symmetry of 4—1—2—1—2, rather like the figure on the left of the illustration above; but in the best circumstances, where the onus of playmaking is shared among the robust workers of this footballing barn, the overall shape would always be pointing leftward on the top, exactly like the other cones shown in the bottom right of the same illustration.

It is in conformity with Allegri’s belligerent interpretation of the 4—3—1—2 system that Milan tries to win games; only a left-footed trickster, Robinho or Cassano, tucked into the mow at the upper tip of the pitch-pine cone, allows Ibrahimovic to complete his crab-walk with perfection, when he has the leisure to bring down the enemy. (Heard of a husking, a week ago; also heard of a man, in San Siro, who sold his fat hog for $75,00 to see that.)

I live where Pinus rigida grows, with its firm cones, almost as hard as iron, armed with recurved spines. I should not be surprised of the evolution from Ancelotti’s ‘Christmas tree’ formation to the current pitch-pine cones. Both shapes provide old-fashioned harvest and entertainment. The base of the pitch-pine cone which, closed, is semicircular, after it has opened becomes more or less flat and horizontal by the crowding of the scales backward upon the smaller and imperfect ones next to the stem; and, viewed on this flat end, it is engaging to imagine the late Seedorf carefully arranged in curving rays. We can perhaps imagine how Milan’s wood looked to Allegri when he took over, and speculate whether it resembled the patchy fog of Viale Certosa, on the southside of the Lombard metropolis, or rather the chaste virginity of seventeenth-century Maine. William Wood—whose very name should rest like a titular deity of rustic dwellings—wrote in New England’s Prospect, of 1633, that

I live where Pinus rigida grows, with its firm cones, almost as hard as iron, armed with recurved spines. I should not be surprised of the evolution from Ancelotti’s ‘Christmas tree’ formation to the current pitch-pine cones. Both shapes provide old-fashioned harvest and entertainment. The base of the pitch-pine cone which, closed, is semicircular, after it has opened becomes more or less flat and horizontal by the crowding of the scales backward upon the smaller and imperfect ones next to the stem; and, viewed on this flat end, it is engaging to imagine the late Seedorf carefully arranged in curving rays. We can perhaps imagine how Milan’s wood looked to Allegri when he took over, and speculate whether it resembled the patchy fog of Viale Certosa, on the southside of the Lombard metropolis, or rather the chaste virginity of seventeenth-century Maine. William Wood—whose very name should rest like a titular deity of rustic dwellings—wrote in New England’s Prospect, of 1633, that

the timber of the country grows strait, and tall, some trees being twenty, some thirty foot high, before they spread forth their branches; generally the trees be not very thick, though there be many that will serve for mill-posts, some being three foot and an half over.

One would judge, from accounts of Boateng’s impact into the Serie A, that tactical instructions were clearer when the wood was primitive, and the underwood was left intact from fire and swamps. Thoreau’s observation about the delicate shedding of winged seeds befits the acclamation of the company of AC Milan, in times of plentiful harvest, when Allegri’s hand-picked midfield wood-cutters chant to the terrace, conspicuous with the scarlet berries of sweat and the leaves of Cornus Florida:

We have ploughed, we have sowed,

We have reaped, we have mowed,

We have brought home every load. . . ♦

Previously in this series: Ibrahimovic’s Crab Walk.