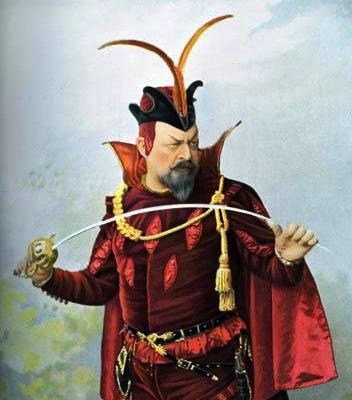

“Ecco il mondo!” Erwin Schrott as Mefistofele (royalmonaco.net)

“Do You Know Faust?”

No subject is better suited to the spirit of Halloween than Faust. The legend of the old philosopher who sold his soul to Satan for youth, sex, riches, and eternal damnation was based on real events — real, that is, from the medieval era’s point of view, where the dark arts were considered as suitable a discipline for study as history and mathematics are today.

The existence of a genuine Doctor of Divinity named Johannes Georg Faust (1480?-1540, or thereabouts), who lived and died in-and-around old Württemberg in Lutheran-era Germany, and was known throughout the realm as a magus, an alchemist, a practical joker, and “conjurer of cheap tricks” (as well as a molester of young boys), gave credence to the notion that he had a made a blasphemous deal with the Devil in exchange for his “magical” abilities.

Indeed, the personage of Faust and his devilish pact have been a recurring theme throughout literature and folklore long before it dawned on playwrights to devote a full-length stage treatment to the matter. The opera world was no exception, for Faust was the protagonist in any number of lyric ventures almost as frequent as that of Orpheus and his myth.

There was a time, from the late nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth, when French composer Charles Gounod’s five-act Faust (1859) dominated both the European and American operatic landscape. Gounod based his once-popular adaptation on Part I of German poet and author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s epic tragedy Faust, first published in 1808 (he only completed Part II near the end of his life). Goethe’s poem took place in medieval Germany, with several of its scenes in Heaven (Prologue to Part I, Epilogue to Part II), and the second half set primarily in Ancient Greece with the fabled Helen of Troy.

Hector Berlioz (en.wikipedia.org)

With both feet planted firmly in Classicism as well as in the Enlightenment, another French-born artist, Hector Berlioz, a precocious child of the Romantic period, imagined his take on the tale, which he dubbed La Damnation de Faust (1846), as a “dramatic legend” for four solo voices, full orchestra, and expanded chorus. Berlioz never considered it an “opera” as such, or a “cantata” in the generally accepted use of the term, but rather as a choral-symphonic piece that exploited every aspect of music and theater, including sonic, dramatic, and scenic elements. In this instance, he was far ahead of Wagner and other musicians of the time in his far-sighted approach to these properties.

The finished product, then, is a work unique to the canon of opera, a psychologically probing, before-its-time pièce de résistance that defies normal description. Based in theory on Goethe’s poem, La Damnation de Faust takes a markedly different turn in recounting its version of Faust’s myth. The Metropolitan Opera presented the work, for only the second time in its history, in the 2008-2009 season, in an elaborate multimedia production conceived and directed by Robert Lepage, the brain behind the company’s recent Ring of the Nibelung.

The Met also unveiled a new production of Gounod’s woe-begotten Faust in 2011, a positively dreadful presentation that made the old warhorse look like Dexter’s laboratory, a Fritz Lang rip-off of Doctor Atomic, John Adams’ contemporary riff on the atomic bomb tests at Los Alamos, New Mexico.

Leaving the past behind for the moment, one can see that a strange thing has happened in the world of grand opera. Mind you, I do not know the precise moment it occurred, but the once positive image most individuals had of Gounod’s Faust, in addition to the negative one in re Berlioz’s Damnation, has been changing and evolving for a number of years now.

Edouard de Reszke as Mephistopheles in Faust (voice-talk.net)

My own opinion about Gounod’s delicate, aromatic flower has shifted with the tide. I used to think of his Faust as the be-all and end-all of Romanticism. At the time (and I’m talking the mid- to late 1970s and 80s), I was enamored of the opera’s fragrant melodies, its filigreed air of Victorian quaintness and charm, along with its rudimentary expression of the eternal conflict between good and evil — or rather, the contrast between the carnal and spiritual natures of man. In a staging worthy of its ambitions (for example, Frank Corsaro’s revolutionary one for New York City Opera in the mid-1960s and 70s), Faust can move an audience to tears and cheers; and those melodies can stir one’s soul like nothing else we know.

Still, this may have been too heady a subject even for Gounod to tackle. At the behest of impresario Léon Carvalho, whose spouse, Marie Miolan-Carvalho, starred in the pivotal role of Marguérite during the opera’s premiere run in Paris, Gounod and his librettists expunged the hitherto philosophical aspects from his work. What remained of the original concept was a long, ungainly spectacle with an intrusive Act IV Walpurgis Night ballet sequence — fabulous music, no doubt, but suspected of having come from the hand of composer Léo Delibes.

And with respect to Berlioz’s once maligned creation, it is presently considered a masterpiece of orchestral and choral writing, with the vocal demands placed upon its three protagonists (in particular, that of the tenor) among the most daunting in the active repertoire. This reversal of fortune, however, has not made it any easier to produce La Damnation de Faust, which leaves an ever-widening gap in the legacy of Faust subjects for the operatic stage.

“Hail, Lord of Heaven”

Arrigo Boito (en.wikipedia.org)

Taking up the slack, we still have Arrigo Boito’s fabulous Mefistofele to admire and grab onto, for which we can all be grateful. This problematic work premiered at La Scala, Milan, in 1868 and became, in short order, one of opera’s most ignominious failures. It was withdrawn after two further performances, and presented anew in 1875-76 with whole scenes excised and new material (from an earlier failed opera, Ero e Leandro, for which Boito provided the text) added to it, i.e., the lovely “Lontano, lontano, lontano” duet for Margherita and Faust in Act III.

In this writer’s estimation, Mefistofele is the most accurate representation yet of Goethe’s epic vision, with Boito’s grandiose music bringing a much-needed majesty to the story. More strongly influenced by Berlioz than by either Wagner or Gounod (note the marvelous brass fanfares and harmonic choral effects of both the Prologue and Epilogue to Mefistofele — a clear reference to Berlioz’s Les Troyens), Boito, in the guise of a musical magus, conjures up a justly depraved “hero” in Mefisto: red of claw, sly of humor, vicious in vocal expression, and rancorous in temperament, the title character (sung by a high-profile bass-baritone) emerges as the fiendish lead of sorts, appearing in every scene and engaging the audience’s sympathy, in the most extraordinary tidal wave of unamplified sound to be heard in present-day opera houses.

In comparison, Gounod’s gentlemanly Méphistophèles (where the Devil makes quite the cavalier) and Berlioz’s edgier conception of the character are satanic babes in the woods. Boito allows his Lucifer to thunder and roar, spouting defiance in the face of defeat at the hands of the heavenly hosts. Where God allowed Satan to test the faith of Job in the Old Testament Book of Job, so Goethe reimagined his poem as a reflection on man’s acceptance of his lot in life, by forcing him to wander through the circles of purgatory and redemption (a reference to Dante’s Inferno), until finally arriving at the starting point: “From heaven through earth to hell, and back to heaven,” Goethe proclaimed, with “Faust himself, the hero… the representative man, the type of humanity in its contest with the obstacles and temptations within and without, which beset his path.”

Prologue to Mefistofele (grimaldiforum.com)

Although musicologists find Boito’s treatment to be episodic (due to its composer having trimmed the work down to a more “manageable” length after its disastrous premiere), there is near universal praise for Mefistofele’s various sections. For example, the Prologue has been an established concert favorite with the world’s symphony orchestras and choral societies almost from the start. Several of the work’s airs, beginning with “Ave Signor” (“Hail, Lord of Heaven”) from the Prologue, to the first act’s “Son lo spirito che nega” (“I am the spirit that denies”), and the Act II solo “Ecco il mondo” (“Behold the world”), have expanded and enriched the bass repertory for generations. The two vocally pleasing turns for tenor, “Dai campi, dai prati” (“From the fields, from the meadows”) and “Giunto sul passo estremo” (“Having arrived at the end of my life”), have attracted star singers from the dawn of recording. And the soprano’s impressive Mad Scene from Act III, “L’altra notte in fondo al mare” (“The other night, into the depths of the sea”), with its plaintive, introductory flute obbligato and melancholy sense of impending doom (similar in conception to Desdemona’s Willow Song from Verdi’s Otello), echoed the ravings of Shakespeare’s Ophelia in Hamlet to delightful effect.

The Shakespearean analogy is no mere coincidence. Boito was, after all, a man of letters. In his later years, the intellectually curious poet forged a well-documented alliance with Italy’s greatest living opera composer, Giuseppe Verdi, which led to Boito’s writing of the librettos for Otello and Falstaff, both based on Shakespeare plays, along with providing a revamped Council Chamber scene for Verdi’s earlier Simon Boccanegra. He also wrote the text for his own Mefistofele and the unfinished Nerone, as well as for Amilcare Ponchielli’s La Gioconda, which shares similar musical material and structure with Mefistofele. Boito was also close friends with Brazilian composer Carlos Gomes and maestro Arturo Toscanini, who completed and conducted Nerone in Milan upon Boito’s death in 1918.

So much for the man behind the curtain — now, for the opera itself!

(To be continued…)

Copyright © 2013 by Josmar F. Lopes