Here, There and Everywhere

Heitor Villa-Lobos – Doodle on Google

A little known aspect of Villa-Lobos’ overseas exploits involved his first tour of the United States, where, in November 1944, he was called upon to conduct a series of concerts of his works (at the invitation of maestro Leopold Stokowski) at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles. He quickly followed this assignment up with guest appearances in such places as Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and New York.

He even presided over some of the country’s foremost music ensembles, among them the New York Philharmonic in a performance of his Choros Nos. 8 and 9, and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. A natty dresser and even livelier conversationalist, Villa most assuredly would have made the rounds of TV talk shows had they existed back then. While visiting the Big Apple, Villa did the next best thing: he sat down for an interview with New York Times critic Olin Downes, an admirer of his oeuvre, who asked the Brazilian if he used folk music in his compositions. “Never,” was the composer’s reply. “I compose in the folk style; I utilize thematic idioms in my own way, and subject to its own development. An artist must do this. To make a potpourri of folk-melody, and to think that in this way music has been created, is hopeless. It is only nature and humanity that can lead an artist to the truth.”

Incredibly, a newly formed American appreciation for the composer’s music eventually cleared the way for the Broadway production of Magdalena, his “musical adventure in two acts.” The background of this work’s evolution is an intriguing yet lighthearted tale of behind-the-scenes bargaining and cajoling, well documented in various writings, among them the essay, “Villa-Lobos on Broadway,” by Brazilian conductor Ricardo Prado, and in particular the program notes for the only existing recording of the piece, written by the show’s lyricists, Robert “Bob” Wright and George “Chet” Forrest.

Chet Forrest & Bob Wright (masterworksbroadway.com)

Conceived by producer Edwin Lester, president of the Los Angeles Civic Light Opera Association, with a book by Homer Curran and Frederick Hazlitt Brennan, and lyrics by the team of Wright and Forrest (Song of Norway, 1944; Kismet, 1953), the show has been somewhat inaccurately described as a south of the border rip-off of Franz Lehár’s The Merry Widow or, to be precise, a Viennese operetta without the schmaltz.

“Set deep in the Colombia jungle on the shores of the Magdalena river,” wrote Thomas G. C. Garcia, a noted teacher and ethnomusicologist at the State University of West Georgia, “the story is replete with pagan Indians, banana republic military figures, a shrine to the Miracle Madonna, marital and political intrigue, death by overeating [Author’s note: It’s not quite so revolting as it’s made to sound], and the triumph of justice at the end; it is not unlike many operas and operettas of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries,” Garcia went on.

Donal Henahan, former music critic for the New York Times, summarized the action of the musical in typically dry fashion: “Magdalena is about the contrast between the goodness and religious fervor of exploited Colombia jungle people and the epicurean decadence of civilization, epitomized by Paris.” Voilá!

Continued Professor Garcia, “Although set in Colombia, composed by a Brazilian composer to an English libretto by an American playwright, Magdalena was produced at [a] time in which Latin American music was generally presented as part of one homogenous mass, not as part of distinct cultures.”

Garcia’s argument had merit. Having presented his case, he then went on to recount the “homogenous” nature of Latin culture, as practiced by Hollywood musicals of the war years. “Because of the prejudices and misconceptions regarding Latin American culture and music, critics assumed Magdalena to be based on Colombian ‘jungle music,’ and that Villa-Lobos, because he was Brazilian, had intimate knowledge of the music of South America in general and specifically the music of the Colombian jungle.” Garcia quotes newspaper reviews of the time as proof of his assertions, although it’s conceivable he might have mistaken these glowing reports for “expert testimony,” which they clearly were not. Still, his point was well taken.

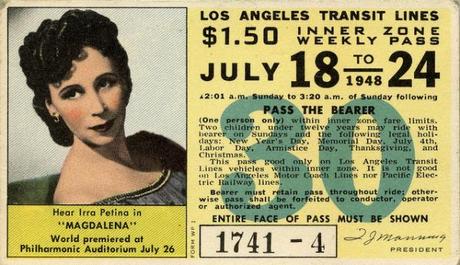

Composed between January and March of 1947, Magdalena had its premiere at Philharmonic Hall in Los Angeles on July 26, 1948; it then ventured north to San Francisco where the show enjoyed a 32-performance run, before making its Broadway bow. But how did Magdalena actually come about? Neither Forrest nor Wright had ever met Villa-Lobos, even though they were aware of his reputation, especially after his Hollywood Bowl excursion; nor did they have the slightest clue as to how to approach him.

According to our lyricist friends, only a title and the names of one or two characters were all that existed of the plot at that point, thanks to some quick thinking by Curran, a “West Coast theater man and one of America’s outstanding showmen.” Forrest and Wright could not have believed their good fortune when their agent, George Wood, of William Morris, relayed the news that he was able to finalize the deal with Villa, and (wonder of wonders) obtain a written contract “within days” of his initial contact with the composer who, as luck would have it, just happened to have been on the agency’s list of clients.

What transpired next is a textbook example of placing the American cart before the Brazilian horse. Forrest and Wright worked out their “dream cast” with Curran, which included some of Broadway’s most illustrious personalities. No sooner had this been settled when publicity for the venture started to mount. To take their dream to the next level, the lyricists made plans to go to Brazil and meet with Villa-Lobos personally. After flight cancellations and several aborted attempts at a takeoff, the frustrated pair got as far as San Juan, Puerto Rico, where they cabled Villa-Lobos to inform him of their inability to secure safe passage to Rio. A short while later, Villa cabled back, indicating that he and his wife Arminda, along with his accompanist-interpreter José Brandão, would be coming to New York instead. Another stroke of luck!

Brandao, Forrest, Arminda, Villa & Wright (museuvillalobos.org.br)

After a round of meetings over lunch, Forrest and Wright began to realize that their cigar-chomping, demitasse-drinking companion “was clearly confused as to what was expected of him, and how we planned to use his music.” That was the least of their problems: the men also learned that no one at the agency had bothered to explain to their visitor the “notion of what his, and our, contracts called for,” nor was Villa aware of the songwriters’ connection to Song of Norway, let alone to anything else on Broadway.

The project appeared to be on the verge of total collapse. Perhaps out of sympathy for the composer’s situation (and their own eagerness to begin work on the project), Forrest and Wright decided to clear the air regarding their business relationship — a wise move on their part. Consequently, they urged Villa to consult with the home office, to “have them spell out the facts of his contractual commitments, and ours, and then decide what he wanted to do.”

Fearing all was lost, the men were pleasantly surprised when later that evening a practically teary-eyed Villa-Lobos returned to their hotel with “hat in hand,” so to speak. In as contrite a manner as possible, given the language barrier — to be kind, Villa’s grasp of English was at best rudimentary — he agreed to hand over his works to his younger colleagues (Wright and Forrest were 33 and 34, respectively, to Villa’s virile 60).

Overcoming the pair’s willingness to “fiddle around with Villa’s melodies the way they had done with Edward Grieg’s [for Song of Norway], which the composer absolutely could not tolerate,” was another, almost insurmountable hurdle that was deftly handled. “But Grieg is dead,” Villa persisted, “and I live” (translation: he was alive and kicking and available for consultation). What Villa offered instead was a one-on-one collaboration. Even better, they thought. Seven weeks later, their dream of a “musical adventure” became a reality.

Music to Try Men’s Souls

“My Bus and I” from Magdalena (Teatro Municipal, Sao Paulo)

Despite the air of camaraderie present throughout its composition, Magdalena came at an especially trying time for the composer, who was diagnosed shortly thereafter, in Rio, with “inoperable, terminal cancer” of the bladder. Fortunately for all concerned, Villa-Lobos was flown to New York and immediately hospitalized at Memorial Hospital, supposedly on the same night (September 20, 1948) as the Manhattan premiere at the Ziegfeld Theatre. Other sources maintain the operation took place the day before the Los Angeles premiere two months earlier. Nevertheless, all were in agreement that a simultaneous musician’s strike was called prior to the New York opening, which crippled plans to broadcast radio excerpts and record the original-cast album, de rigueur for shows back then.

Fortunately, both Villa and “Mindinha” eventually attended a performance of their “musical adventure” just as the show was about to close. According to reports, the couple was thrilled with the results. The wonderful lineup of stars assembled for the run included Metropolitan Opera diva Irra Petina as Teresa, bass Gerhard Pechner as Padre José, singer-actor John Raitt (of Carousel fame) as Pedro, soprano Dorothy Sarnoff as Maria, Czech actor-director Hugo Haas as General Carabaña, John Schickling as Zoggie, and Ferdinand Hilt as Major Blanco. American movie producer Jules Dassin directed the work for the stage, and choreographer Jack Cole handled the dance portions.

Irra Petina, a souvenir from the premiere (flickr.com)

Boasting a convoluted plot and exotic South American locale, this lively Latin-American extravaganza basically revamped many of Villa-Lobos’ previous themes (as critic Robert Garland was quick to point out: “Heitor Villa-Lobos isn’t too shy to borrow from himself occasionally”), with the music taken in part from sections of the Bachianas Brasileiras, as well as the folk arrangements to be found in his wide-ranging, eleven-volume Guia Prático (“Practical Guide,” 1932) of over 60 piano pieces, along with his Ciclo brasileiro (1936-37), which was based on rural folk music, and other Brazilian-related styles, including choro, modinha and seresta.

If you listen closely to “Food for Thought,” that deliciously catchy number from the Paris sequence of Act I, you can hear the rhythmic strains (in a minor key, of course) of the “Habañera” from Bizet’s Carmen.

With that said, there is some conjecture as to whether or not Villa-Lobos had conceived his operetta “sight unseen” and without benefit of the printed text. Despite Forrest and Wright’s assurances that “every note of the score is original and exactly as Villa-Lobos wrote it,” musicologists have noted that (quoting Garcia again) “Great differences [exist] between the show’s score and Villa-Lobos’ manuscript [which] indicate that there was indeed some arranging and adapting, principally because Villa-Lobos composed the work without a libretto (he had only a sketch of the story). Even if Villa-Lobos had had a libretto, he spoke and read virtually no English — at any rate, his score has no lyrics whatsoever.”

Garcia concluded that Villa “knew the story and provided his collaborators with a manuscript indicating when and what characters should sing. The biggest difference is that Villa-Lobos’ manuscript contains dozens of pages of orchestral interludes that were omitted from the show’s score. Assuming that Villa-Lobos’ partners did nothing other than adjust the score in order to add lyrics and cut orchestral interludes, they did not arrange Villa-Lobos’ music; Villa-Lobos, however, did.”

Despite favorable reviews for the music (“Dazzling,” “Rich, warm and original,” “bountiful and varied,” “spirited and lovely,” a “gem of a score,” and “the finest, most sophisticated score in a generation”), the musical came and went in less than three months. Surprisingly, Villa-Lobos’ disappointment with the entire Broadway enterprise was expressed through conductor Ralph Gustafson, in his memoir “Villa-Lobos and the Man-Eating Flower”:

“The opening night of Magdalena was both a success and a disaster. The triumph belonged to Villa-Lobos — some of it to the choreography of Jack Cole, and some of it to the color of the sets and the costumes. But the libretto and lyrics were disastrous and the run lasted only eleven weeks…While he was in Rio and while he was in the hospital, [Villa-Lobos] told me, those who should have known better ‘cut and damaged’ his score. The music director was ‘[an] imbecile.’ Then there was the useless extravagance: ‘The flowers in one scene cost $5,000. I would write another operetta for that!’ The whole undertaking was too much. ‘Now I am finished with Magdalena.’”

So, was Villa-Lobos impressed with what Forrest and Wright had done with his music, or not? If he hadn’t liked their handiwork, then why didn’t he express his outrage at the time? If he had liked it, why did he complain about it later on, and to a third party uninvolved in its creation? It may have been partially out of courtesy that the worldly Villa, a man accustomed to the best the musical world had to offer, decided not to offend his colleagues’ sensibilities to their faces — a typically selfless Brazilian gesture, I can assure you. He certainly had the warmest feelings for his working partners, deservedly so. Besides, an individual’s views about a work can understandably change over time. But with Villa, they were in a constant state of flux. All we are left with is the finished product, which can speak for itself.

Magdalena CD cover (amazon.com)

Magdalena has since been produced several times across the U.S., and there exists a hard-to-find Sony® compact disc (re-released by the Archiv label) commemorating a live, 1987 Alice Tully Hall concert performance, starring Judy Kaye, George Rose, Faith Esham, Kevin Gray, Jerry Hadley (who replaced John Raitt at the recording sessions), Keith Curran, Charles Damsel, and Charles Repole, in honor of the centennial of the composer’s birth. The adaptation was credited to conductor Evans Haile.

The verdict rendered by Times critic Donal Henahan (in his November 25, 1987 review), however, dealt a fatal blow to future revivals: “What resulted instead, based on this concert performance, was a work marginally more interesting than most Broadway products of its time but one hard to take seriously today except as a curiosity… On the whole, a valiant effort, but it is likely that Magdalena can safely be returned to its shelf in the old curiosity shop.” Ouch!

For all intents and purposes, Heitor Villa-Lobos’ “musical adventure in two acts” remains a “curiosity” and comparatively unknown, even in its native Brazil.

(End of Part Five)

Copyright © 2013 by Josmar F. Lopes