To seek in the bright sky a place for freedom and unrestraint. – Liu Rushi, “On the Kite”

The gender roles of traditional Asian cultures were even more rigid and uncompromising than those of contemporary European cultures, but harlots have always stood outside of the limits their societies set for “good” women. Where “good” women were expected to be chaste, whores were promiscuous; where “good” women were expected to be meek, whores were bold; where “good” women were expected to be ignorant, whores were well-educated; where “good” women were supposed to be submissive, whores accepted or rejected clients as we pleased; and where “good” women were prisoners of convention, whores flouted it. And despite the feminist claims that men prefer women as ovine as possible, and that the patriarchal system is set up for men’s benefit at women’s expense, yet men have throughout history sought out the company of (and paid high prices for) women who were not only their equals, but often their superiors. Like other courtesans, Liu Rushi ignored the rules her society set for “good” women, but unlike others she often ignored the rules it set for any women.

Yang Ai was born in 1618 to a poor family of Zhejiang province, but her exceptional looks and intelligence allowed her family to sell her at the age of eight to the courtesan Xu Fo for training in the profession. She learned so well that Xu was able to place her as a concubine to the prime minister, Zhou Daodeng, soon after she turned thirteen; however, Zhou died a year later and his widow threw her out of the household. She sought out the famous poet Chen Zilong, whom she had met at Zhou’s house a few months before; he took her in as a concubine and the two fell in love and exchanged many poems. Unfortunately, Madame Chen was just as jealous of her as Madame Zhou had been; when Chen went to take the Imperial Examination in 1635, she abused the poor girl so terribly that she fled back to Xu Fo, who now owned a brothel. When Xu married in 1638, Yang Yin (as she now called herself) took over the management; she was already famous as a poet and painter by this time, and published three collections of poetry between 1638 and 1640. But though she was doing well financially, she craved the stability of marriage; when a regular client named Song Yuanwen kept promising to marry her but never followed through, she is said to have thrown him out in a violent tantrum.

Yang Ai was born in 1618 to a poor family of Zhejiang province, but her exceptional looks and intelligence allowed her family to sell her at the age of eight to the courtesan Xu Fo for training in the profession. She learned so well that Xu was able to place her as a concubine to the prime minister, Zhou Daodeng, soon after she turned thirteen; however, Zhou died a year later and his widow threw her out of the household. She sought out the famous poet Chen Zilong, whom she had met at Zhou’s house a few months before; he took her in as a concubine and the two fell in love and exchanged many poems. Unfortunately, Madame Chen was just as jealous of her as Madame Zhou had been; when Chen went to take the Imperial Examination in 1635, she abused the poor girl so terribly that she fled back to Xu Fo, who now owned a brothel. When Xu married in 1638, Yang Yin (as she now called herself) took over the management; she was already famous as a poet and painter by this time, and published three collections of poetry between 1638 and 1640. But though she was doing well financially, she craved the stability of marriage; when a regular client named Song Yuanwen kept promising to marry her but never followed through, she is said to have thrown him out in a violent tantrum.

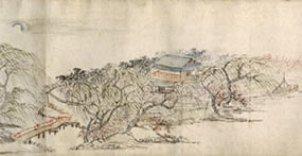

It was during her time as a madam that her androgyny began to assert itself; though her romantic poems were conventionally feminine, she also wrote in a masculine, “heroic” style and often left the narrator’s gender ambiguous. In letters she favored gender-neutral terms for herself, and her calligraphy is distinctly masculine, using the “wild grass” style. Her gender-bending behavior reached its zenith in 1640, when she decided to marry the famous scholar and poet Qian Qianyi. She traveled to his home in her boat, dressed in men’s clothing, and asked Qian to give her his opinion on one of her poems. He told her the poem was excellent and asked to see more, but before she left she made sure she let him see the small (bound) feet which left no doubt as to her sex even if he had been fooled at first. The combination of her writing and her intriguing behavior captured his attention, and they were married in 1641. Though she was only his concubine, they had a formal ceremony and he treated her as though she were a full wife, despite this being considered improper. He gave her the nickname Hedong, which she often used in her writing thereafter; it was one of about twenty different names she used at different times and for different purposes. The name by which she is best known, Liu Rushi, came from her continuing habit of cross-dressing; she would sometimes go on errands as her husband’s representative while dressed in his formal Confucian robes, for which people nicknamed her “rushi” (“gentleman”).

It was during her time as a madam that her androgyny began to assert itself; though her romantic poems were conventionally feminine, she also wrote in a masculine, “heroic” style and often left the narrator’s gender ambiguous. In letters she favored gender-neutral terms for herself, and her calligraphy is distinctly masculine, using the “wild grass” style. Her gender-bending behavior reached its zenith in 1640, when she decided to marry the famous scholar and poet Qian Qianyi. She traveled to his home in her boat, dressed in men’s clothing, and asked Qian to give her his opinion on one of her poems. He told her the poem was excellent and asked to see more, but before she left she made sure she let him see the small (bound) feet which left no doubt as to her sex even if he had been fooled at first. The combination of her writing and her intriguing behavior captured his attention, and they were married in 1641. Though she was only his concubine, they had a formal ceremony and he treated her as though she were a full wife, despite this being considered improper. He gave her the nickname Hedong, which she often used in her writing thereafter; it was one of about twenty different names she used at different times and for different purposes. The name by which she is best known, Liu Rushi, came from her continuing habit of cross-dressing; she would sometimes go on errands as her husband’s representative while dressed in his formal Confucian robes, for which people nicknamed her “rushi” (“gentleman”).

Rushi had finally found the stability she sought, but it was not to last long. The Ming Dynasty her husband served collapsed in 1645, and she had become so deeply patriotic by that time she actually tried to persuade him to martyr himself by committing suicide; instead, he surrendered, served as an official to the new Qing regime for five months, then quit and joined the resistance. Liu Rushi joined him and the two were active in the movement for over a decade thereafter; much of Qian’s poetry from the 1650s depicts her as a courageous Ming loyalist. But in 1663, her life started to spin out of control. First, the Qing finally crushed the last Ming resistance, burning her husband’s enormous library in the process; she was so aggrieved she took Buddhist vows. Qian’s spirit was broken, and he died the following year; his creditors and enemies then began to hound Liu Rushi for money. Alone again for the first time in decades, too old (at 46) to return to her former profession and deeply bereaved by the loss of both beloved husband and beloved cause, she was pushed over the edge by the legal persecution and hanged herself in 1664. But though her life ended in despair and tragedy, her own poetry and that of her husband had already made her a legend; the historian Chen Yinke’s said she “embodies the independence of spirit and freedom of thought of our people”, and others have called her “the most respectable prostitute in Chinese history”.

Rushi had finally found the stability she sought, but it was not to last long. The Ming Dynasty her husband served collapsed in 1645, and she had become so deeply patriotic by that time she actually tried to persuade him to martyr himself by committing suicide; instead, he surrendered, served as an official to the new Qing regime for five months, then quit and joined the resistance. Liu Rushi joined him and the two were active in the movement for over a decade thereafter; much of Qian’s poetry from the 1650s depicts her as a courageous Ming loyalist. But in 1663, her life started to spin out of control. First, the Qing finally crushed the last Ming resistance, burning her husband’s enormous library in the process; she was so aggrieved she took Buddhist vows. Qian’s spirit was broken, and he died the following year; his creditors and enemies then began to hound Liu Rushi for money. Alone again for the first time in decades, too old (at 46) to return to her former profession and deeply bereaved by the loss of both beloved husband and beloved cause, she was pushed over the edge by the legal persecution and hanged herself in 1664. But though her life ended in despair and tragedy, her own poetry and that of her husband had already made her a legend; the historian Chen Yinke’s said she “embodies the independence of spirit and freedom of thought of our people”, and others have called her “the most respectable prostitute in Chinese history”.