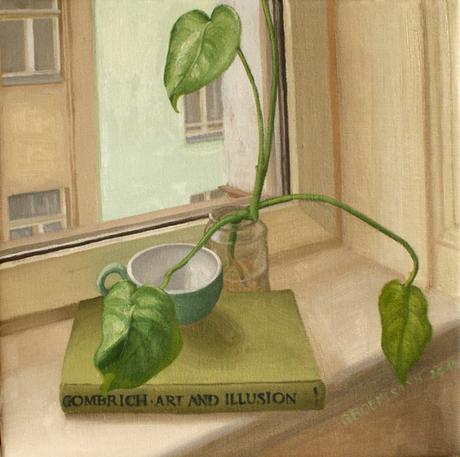

Anfang © Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

Paintings, as we’ve discussed before, are to be seen. The painting, the work itself, is an object, not merely an image. It has what philosophers might call ‘extension’ in the physical world—stretcher bars, linen, three-dimensional paint caked on the surface—and it arguably exists autonomously, divested of its author. If such an object is worth seeing in person, irrespective of its originator, we should consider how it might be seen. There is no doubt that paintings must be exhibited, but in what manner ought this exhibition happen?

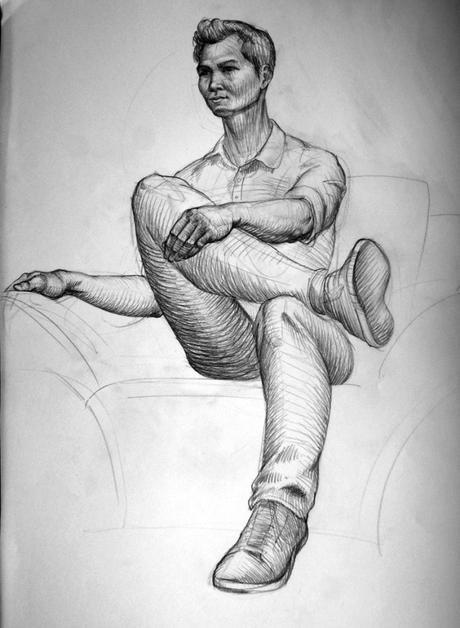

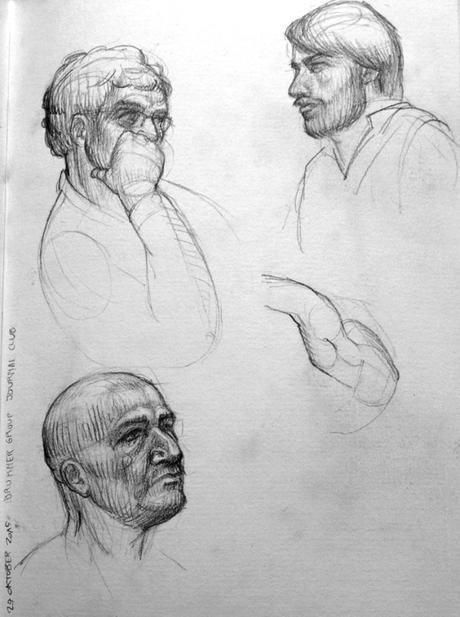

Conrad

Conrad, one of my trusted book-recommenders, gifted me Gertrude Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas and I spent the Festtagen indulging in her reminiscences of early twentieth-century Paris. Thinking about how painters are marketing their work now, renting gallery space, paying commission to private galleries, entering competitions, paying for residencies for the opportunity to exhibit under prestigious organisations, and even pushing their wares in the overwhelming monstrosity that is the international art fair, I was especially taken with how Stein’s companions forged their paths, and her instrumental role in their success. The crux of the matter seems to be that Gertrude Stein herself recognised something of value, and acquired that thing for herself, cherished it, and shared it. How different this attitude is from that of considering a painting a product that may or may not float in the marketplace.

Gertrude Stein and her brother collected paintings. They bought the paintings that really struck them, that they genuinely appreciated. They hung them in their Parisian apartment, as ‘Alice Toklas’ (2001: 10) describes:

‘The home at 27 rue de Fleurus consisted then as it does now of a tiny pavillon of two stories with four small rooms, a kitchen and bath, and a very large atelier adjoining. Now the atelier is attached to the pavillon by a tiny hall passage added in 1914 but at that time the atelier had its own entrance, one rang the bell of the pavillon or knocked at the door of the the atelier, and a great many people did both, but more knocked at the atelier. I was privileged to do both. I had been invited to dine on Saturday evening which was the evening when everybody came, and indeed everybody did come.’

Gertrude Stein’s collection was eclectic, and she began to make the acquaintance of the painters she collected, who began to come to her apartment for meals. In their mid-twenties, she and Pablo Picasso forged an intimate friendship through these very dinners and the portrait sittings they led to. Matisse became a regular guest and dear friend. Painters from disconnected quarters of Paris began to converge in the social hub of the rue de Fleurus, and in their wake, a string of curious art admirers. Toklas (2001: 14) describes the intimidating collection of paintings, unsettling paintings that existed at the periphery of the established art institutions, which flooded Stein’s atelier:

‘They completely covered the white-washed walls right up to the top of the very high ceiling. … It is very difficult now that everybody is accustomed to everything to give some idea of the kind of uneasiness one felt when one first looked at all these pictures on these walls. In those days there were pictures of all kinds there. … At that time there was a great deal of Matisse, Picasso, Renoir, Cézanne but there were also a great many other things. There were two Gaugins, there were Manguins, there was a big nude by Valloton that felt like only it was not like the Odalisque of Manet, there was a Toulouse Lautrec.’

Stein’s collection began with the value she personally saw in these ambitious new works, and extended to friendship with the people behind them. She seems to have recognised both the work as an object of value, and the originator as a fragile conduit for the bringing of such objects into the world: the painter needed to be sustained in order to bring these objects into being. And sustain them she did, with friendship, intellectual discourse, interesting and varied society, food and the purchase of countless paintings.

Brukner group journal club

Despite the worth she personally attached to these paintings, Stein (2001: 17) rather off-handedly comments that ‘at that time these pictures had no value and there was no social privilege attached to knowing anyone there,’ with the result that ‘only those came who really were interested.’ This revealing statement demonstrates an important attitude: that ‘value,’ as we normally speak of it, is all tied up in monetary worth, in the demand for products in a market. Stein’s language betrays this attitude, though her actions demonstrate her ability to find and nurture a different sort of value.

And the contrast is stark: if we begin by considering the painting as a product, we are forced to think how to attribute monetary worth to it, how to convince people that they desire or need such a product; in short, to create demand. If there is one thing to learn from Gertrude Stein about the value of art, it is to turn this idea on its head and start from the other end. Yes, the painting is an object, but not a product, and its value takes a certain insight, a certain understanding, to see. It is an autonomous object left behind in the world, enriching the world in an intangible, difficult to define manner. But it is also a visual stand-in for an idea that has the power to leave its mark on our intellectual landscape. It is the signal of a person who originates such an idea, a person existing in the world and striving to articulate that idea while they yet live. It is a physical sign pointing to a collective of thinkers who cluster around that idea, and in this sense a physical gateway into an intellectual circle. Behind a painting of real worth is an idea that exists in living beings.

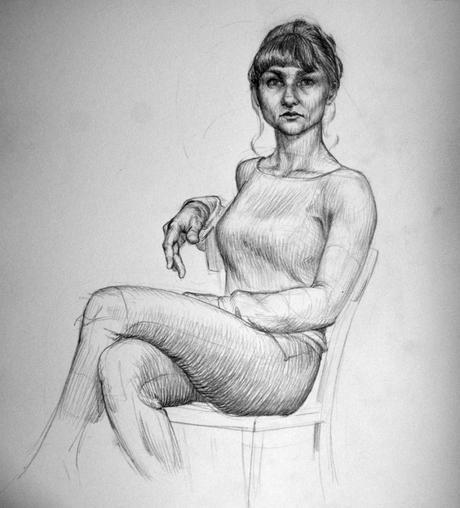

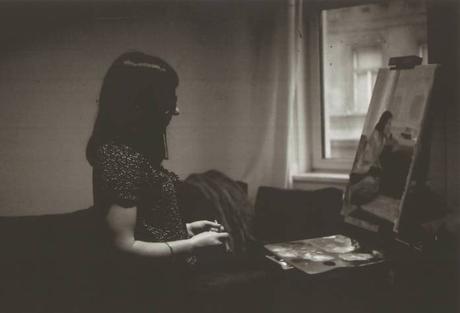

In my studio © Sasablanik

Stein’s atelier burgeoned into a hive of activity. Having seized upon an idea, and gathered about her the people who harboured this idea inside themselves and expressed it in their works, interest in these paintings and in these people grew organically. The atelier would be populated with ‘scattered groups, single and couples all looking and looking.’ Stein would mingle, joining the various discussions. She (2001: 17) would respond to knocks at the door: ‘and the usual formula was, de la part de qui venez-vous, who is your introducer. The idea was that anybody could come but for form’s sake and in Paris you have to have a formula, everybody was supposed to be able to mention the name of somebody who had told them about it. It was a mere form, really everybody could come in and as at that time these pictures had no value and there was no social privilege attached to knowing any one there, only those came who really were interested.’

But soon, more were interested than was really practical. Though things began slowly—‘little by little people began to come to the rue de Fleurus to see the Matisses and the Cézannes,’—the invitees began to come ‘at any time and it began to be a nuisance’ (Stein, 2001: 47). The curiousity of the well-decked atelier of 27 rue de Fleurus naturally demanded its own form, and that form became ‘the Saturday evenings,’ the weekly dinners that Stein would host for artists and intellectuals and passers-through and those newly arrived in Paris.

27 rue de Fleurus emerged as a very particular way in which to see paintings, a truly independent alternative to the official salons of Europe. Matisse gained a following by exhibiting in the more orthodox manner, showing ‘in every autumn salon and every independent. Picasso, on the contrary, never in all his life has shown in any salon. His pictures at that time could really only be seen at 27 rue de Fleurus’ (Stein, 2001: 72). Picasso’s influence extended from the Saturday sessions at Gertrude Stein’s house, and found its way into the salons by way of his followers (Stein, 2001: 73). The salon was not redundant, but it was not the only way to have one’s paintings seen, nor to gain international reknown.

A third element remains to this story of artworks making their way into the world and being seen. Stein writes with palpable respect for Parisian ‘picture dealers’ who believed in the idea rather than cautiously making profit-driven transactions. ‘There are many Paris picture dealers who like adventure in their business,’ she writes (Stein, 2001: 261). She continues:

‘In Paris there are picture dealers like Durand-Ruel who went broke twice supporting the impressionists, Vollard for Cézanne, Sagot for Picasso and Kahnweiler for the cubists. They make their money as they can and they keep on buying something for which there is no present sale and they do so persistently until they create its public. And these adventurers are adventurous because that is the way they feel about it. There are others who have not chosen as well and have gone entirely broke. It is the tradition among the more adventurous Paris picture dealers to adventure.’

Stein (2001: 60) describes how all the painters in her circle were very grateful to one Mademoiselle Weil who had a bric-à-brac shop in Montmartre, since ‘practically everybody who later became famous had sold their first little picture to her.’ She relates the story of the German Kahnweiler who had worked in England until he had saved enough money to realise his dream of having a picture shop in Paris. He invested heart and soul in the cubists, establishing his gallery in the rue Vignon. Eventually, Stein (2001: 118-19) relates, ‘they all realised the genuineness of his interest and his faith, and that he could and would market their work. They all made contracts with him and until the war he did everything for them all. … He believed in them and their future greatness.’

The attitude of the dealers mirrors Stein’s own: these art buyers saw more than a product, more than a business opportunity. They were able to estimate value in another way, and supported individual painters because they saw these painters as embodying certain ideas that needed to be upheld and disseminated. Of course, the picture dealers had a very difficult role in having to try to make monetary value match up with this other, more difficult to define value that they saw in the works. Perhaps as businessmen and women they were foolish. But as messengers trying to draw attention to something of worth, they acted admirably, and I wonder if they have a counterpart in our own time.

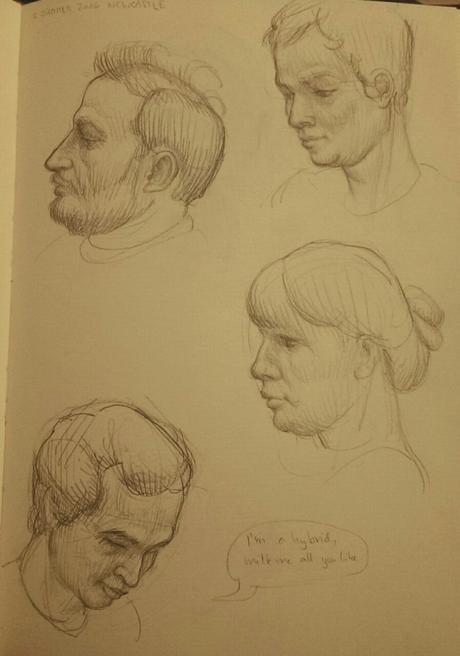

In my studio © Conrad Ohnuki

‘But to return to the pictures’ (Stein 2001: 13). They are supposed to be seen, and we will find a way for them to be seen. Most importantly, this way will unfurl organically, and with the multifaceted support of those who spot a particular kind of value in works of art, and who can’t help but defend this value and stand behind the ideas they esteem.

Stein, Gertrude. 2001 [1933]. The autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. Penguin: London.