Blurred Red Car (Photograph: David Guidas)

I.

I made a point of watching the conclusion of the Eastern and the Western M.L.S. conferences in two obscure diners around Jerome Avenue in the Bronx. Both buildings were heavy pieces of wood and plaster collapsing into ruined gardens, while the Green Line appeared intermittently to be rattling away against the night-blue windows—its ④ sign wavering like a flash looming over black furniture.

The lamplit rooms were deserted, except for a few Chicanos and a man in the armchair near the plasma TV, who remained calm throughout the entire match and kept his cotton Vietnam Veteran cap on, with its embroidered yellow-and-red stripe between two patches of green. A tired-looking woman slumped in a plastic chair slowly, dreamily picking up her spoon from a chili bowl with peanut halves; her grey hair was pulled back tight by a beaded hair barrette with three brown horses (a type I once saw in Santa Fe). Somewhere above the kitchen I heard a loud snap or crack. I quickly realized that I had rushed inside for no reason, fumbling at the door, to get a front seat. From what I could make out of a dismantled Spanish, cascading into strings of word-shells at dazzling speed, these spectators were bored, vaguely non-committal, and ready to take an all-too-familiar footballing broadcast only as the kind of exhibition that astonishes townspeople in market squares, when a black-caped magician removes handkerchiefs from empty paper cones and billiard balls from children’s ears.

Seen from this angle, the two conference finals were an enigmatic performance, viewed by some as a triumph of the South American art of soccer tricksters, by others as a fateful sign of what would happen to the American league once you import champions such as David Beckham from England. The M.L.S., it seemed to me as the fans ran out onto the porch for a smoke, was still at the age of levitations and decapitations, of ghostly apparitions and sudden vanishings. In fact, looking at cabinetmakers and car washers who spent every hour of the day trying to turn each muffled thud into cash, it was not even clear in what sense the New York Red Bulls could be said to withstand the most minute examination of their local fandom. As a tale, the M.L.S. has been created because history is inadequate to our dreams, and the children are always ready to be mesmerized by adults who take off their gloves to make intricate shadows representing American buffalos and Indians, or the golem of Prague.

II.

For the actual final between Houston and Los Angeles, however, I decided to perform a different parlor trick—I still wanted to write of the match by talking instead of the people who watched it, but, oddly enough, I wanted to create a more indistinct, oblique, becalmed experience. I distrusted the proximity of physical bodies in New York City, gathering to cheer for the L.A. Galaxy. What I needed was something else, something else entirely. So I found an available stream at a brightly painted, high-ceilinged coffee shop in TriBeCa that serves a modest variety of salads and panini, and I sat among college students who were nursing terra cotta pots of green tea and writing mid-term papers by aggressively stimulating their white keyboards (most of the people had MacBooks) to the point of obedient orgasm.

One of the coffee shop’s walls featured a kind of American Vintage Repository in convenient plywood cubbyholes, which included a motley collection of The National Geographic issued in the mid-1980s, sepia postcards of the old Yankee Stadium, a deck of cards, a rugged copy of a John Updike hardcover with the fading mark of the National Book Critic Circle Award, a glossy portfolio of an Alpine ski-resort condo with brown chocolates near the sofa, Jay-Z’s soupy autobiography, and a series of glasses carved in a Low German dialect. In between these objects, like waterlogged flowers, one could see wrinkly old comics and covers from Harper’s Bazaar which had been cut-off from the magazine and showed absentminded women of full-bodied curly blond hair, moving their torso as if to dish out a meatloaf in a benign atmosphere and wearing that immaculate, jolly Gwyneth Paltrow air of those who hesitate between beefy sex and squeaky silliness. It was in this extravagant atmosphere that I finally approached the young bartender—herself an amiable Filipino woman, with brassy earrings and a white T-shirt, leaning over the mahoganny desk to squeeze fruit juice into a shaker—and I tried to make a selection out of the home pastries that would last for the whole match. It was a couple of hours before Beckham would pay the M.L.S. Cup the dark homage of his tears that I asked myself: was there a flaw, a little fatal flaw? Was there at the very outset an error in conception that was bound to bring my work to a disastrous end? And what did it even mean—removing my attention, in weariness, from Juninho’s soft thunk thunk dribbling—to ask oneself how was this M.L.S. season? There may have been some lapses here or there, but I was still determined to try and describe from the rough chic of TriBeCa, a moonlit basin where (Landon Donovan claimed) they play the most dirty, cheap soccer of all, how the victory of L.A. Galaxy epitomizes the state of American league.

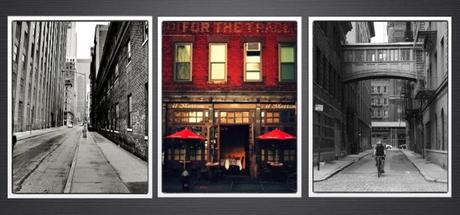

A TriBeCa Triptych

II hadn’t expected my task to be an easy one, in fact I distrusted all forms of predictable work regarding the coalescing new future of the M.L.S., which I keep finding snappish with failure. In my effort to be rigorous I proceeded step by step, from the inside out of the similar, and utterly unfashionable, 4—4—2 offered by Los Angeles and Houston, in the manner of a painter who imagines the musculature beneath the skin, while his subject recedes into vagueness. The communication between the two Galaxy front men did not work well. Space-time relations appeared as new; the sheer oddity of long balls produced a studiedly romantic effect, which the spectators labored to find impossible to resist. Beckham used as a tucked-in holding midfielder gave me the impression of a neglected modernist gem. (Outside a Labrador was moving his joints so effortlessly, in that pet-friendly neigborhood, as if he was swimming in silky waters; his owner was a fit-looking man in his sixties with moleskin trousers and the distinctively weathered face of a farmer who holds a leek-and-potato stand at the Union Square market.) It was only when Beckham was restored as a twisting bluish-red artery on the right wing that Los Angeles could eventually make up a rib cage of a game out of the shading mold they were operating in. It was only when Donovan himself, longing for release, moved permanently into the center of the attacking force that careful prudence gave way to a parallel realm of possibilities—a realm obedient to the raw laws of physics but utterly discarnate from the tactical developments of European football.

Watching the M.L.S. final in a coffee shop is not so different from reading a book of short stories by Mavis Gallant in a coffee shop: most other people there probably don’t know or care what it is—plus both products are printed or presented in very small font that’s illegible at a distance of more than ten or so feet. And, anyway, we all move through the world harboring thoughts and desires and urges that no stranger could discern by looking at us. The M.L.S. imagines a world in which strangers trade the wildest of these freely, and act on them whenever they please. The disjunction between distance travelled and socio-economic gradient in the American league is—relatively speaking—as extreme as in inner London. (As I reflect about this, the petulant drone of R&B music fades just enough for me to hear a tense conversation through the phone speakers between a young girl and a person with whom, apparently, she’d agreed not to speak with for weeks—her boyfriend, maybe, or ex-boyfriend, maybe, they could never decide what to call themselves.) The liberating amazement of soccer as it swallows yet another province of the world is wrapped up, in the U.S., with the oppression of the vintage tactics it displays to perform the rituals of its entire citizenry. The M.L.S. lures us deeper and deeper into the footballing halls of a Barnum Musem made by cinema shows, spurious texts, false beards, faked fossils, and false-bottomed trunks. Outside my coffee shop everything grows vague, like a trompe l’oeil streetway. Soon enough, this part of the city will be deserted, except for the usual characters—policemen, soccer captains, au pair girls, professional dog-walkers, fast-food cooks—who cling, at night, to a dreamy wakefulness. A garbage-can cover will roll thumping toward the edge of the world, from the fuzzy smoke of the Manhattan rivers to the luminous pointillism of Los Angeles. ♦