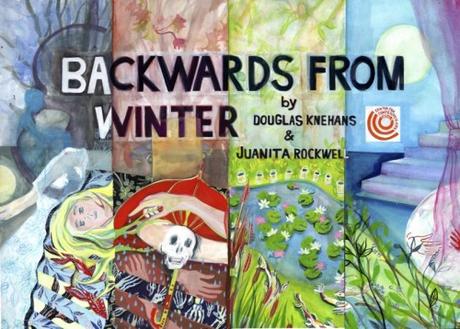

Operatoonity.com interview: Backwards from Winter

presented by The Center for Contemporary Opera

World Premiere: May 25, 2018

Symphony Space, Thalia Theater, New York City

Music: Douglas Knehans

Libretto: Juanita Rockwell

The contemporary opera premieres in NYC May 25 for Opera Fest

Each May, around the time when more conventional opera companies go dark for the summer, New York City’s Opera Fest comes alive. Opera Fest is an indie opera bonanza showcasing new and reimagined operatic works, from virtual reality to improv opera, with productions in theaters, gardens, garages, bars, and playgrounds.

Playwright and librettist Juanita Rockwell

Juanita Rockwell wrote the libretto for a new work premiering on May 25, called Backwards from Winter. The piece is an hour long operatic monodrama exploring a single woman’s reflection on a love relationship as seen through various elemental filters of seasons, color, nature, emotion and memory and told through live voice, live electronic/computer music and multiple video streams.

Some of my favorite operatic works over the years have been the new and reimagined pieces, which breathe vitality and relevancy into the traditional opera repertoire, heavy with centuries’ old works, trotted out again and again, with mixed results.

Since I had the good fortune to meet the award-winning librettist, playwright, lyricist, songwriter and director through the Wilkes University Maslow Creative Writing Program, where she is a Guest Artist Mentor, and delighted in seeing and hearing several of her plays, I thought Operatoonity.com readers might enjoy learning more about her experience as a creator of an upcoming world premiere operatic work.

Welcome to Operatoonity.com, Juanita! What interested you about this project?

It’s always hard to remember origin stories exactly! As I recall, composer Douglas Knehans approached me about creating an opera together, having read about my work online. He actually found me through LinkedIn, if you can imagine. He knew he wanted it to be a monodrama for soprano, electric cello, video and computer, and he knew he wanted it in 4 parts with interludes between the parts. I loved that he wasn’t telling me what story to tell, but had such a clear structural framework. He said he wanted texts about the length of a sonnet for each of the 4 sections. I suggested that we use 3 Japanese Tanka for each section, a 5-line poetic relative of Haiku that has a 5-7-5-7-7 syllabic structure. Tanka, at their best, are condensed diamonds of imagery and emotion, perfect to tell a story of of grief and redemption: in the frozen dark of winter, a woman is in grief over the loss of her beloved. We travel backwards in time with her, through the loss of her love in an autumn storm, through the summer heat of their passion, to the heart-opening spring of their love. The story moves “backwards from winter,” but it is also a story of a woman moving forward, learning to embrace and transcend her grief. Those themes are very close to my heart.

Composer Douglas Knehans

What interested you about this composer?

He’s an amazing composer—his music is profoundly rich in emotion and color, and he’s so inventive, both melodically and technologically. I’d written two other libretti for operas with two composers, very different in musical aesthetic, but neither one had Douglas’s bel canto approach to the interaction of the words and music. It was fascinating for me to get notes on my text that would ask me to replace a word that had an “i” sound with a word that had an “oo” or “ah” sound, for example. Soon I understood that I needed to find vowel sounds that allowed for extended tones and melodic sweeps. By the end of the project, I felt I’d learned a new language that I look forward to using again.

Backwards in Winter premieres at the Symphony Space on the Upper West Side

What was the timeline for this project, from idea to production?

Douglas and I began work together in the spring of 2011. It took us several years to write it, and several more for these two completely different productions—the world premiere in New York City on May 25 and the Australasian premiere at the Dark MOFO in Tasmania June 20-23—to come to fruition within a month of each other. The Center for Contemporary Opera is producing the world premiere at Symphony Space in Manhattan, as part of the New York Opera Fest, directed by Jennifer Williams and featuring soprano Anke Briegel with Jeffrey Krieger on electric cello. IHOS Amsterdam is producing the work in Tasmania as part of Dark MOFO (an amazing festival that seems to be part Lincoln Center and part Burning Man), directed by Konstantin Koukias and featuring soprano Judith Weusten and e-cellist Antonio Pratsinakis.

Which came first, the score or the libretto?

The libretto came first. Tanka, like Haiku, always have some sort of reference to a particular season, so it wasn’t a big step to think of the 4 parts as seasons. Douglas was interested in a theme of oneness, which was a natural fit with the Buddhist and Shinto underpinnings of the Tanka form. I wanted the interludes to feature a single Tanka that was reconstructed out of lines from the previous 3 Tanka. So, it was all a wonderful puzzle designed to tear your heart out.

Can you describe the difference between writing a play and writing a libretto?

For me, I’m not sure it’s as different as you’d think. My approach is always to trick my mind into revealing my heart by preoccupying my brain with formal and structural concerns. One of my favorite playwrights is Samuel Beckett, whose work became more and more essentialized, over the years. So I tend to think more like a poet than a novelist, whether as playwright, librettist or lyricist. And both forms are collaborative, because your work is always filtered and transformed by other artists in the process of creation. I guess the biggest difference is that your primary collaborators as playwright are usually the many artists who create each production. As a librettist, the composer is your primary collaborator and guide. Nothing happens without the composer.

How would you describe your feelings about opera as an art form?

I believe that words and music are fundamentally meant to be together. Even my plays usually have songs and music built into them somehow. But there’s nothing as thrilling as opera.

How do you feel about contemporary works being the future of opera?

I enjoy many kinds of opera and music-theatre, but I am unquestionably most interested in contemporary work. And the variety of the work being created today is richer and more varied than at any time in history. I love the experimentation, the crossing of boundaries, even the so-called failures—which so often turn out to be the basis for the next amazing step forward in the form! I think it’s great that there are still some moving interpretations and transformations of historic pieces, but there is no future for opera if there don’t continue to be productions of new work.

* * *