[Pauling and the Vietnam War, Part 5 of 7]

“If President Johnson had to kill – shoot, burn to death – ten Vietnamese women and children every morning before breakfast, the war would soon end.”

-Linus Pauling, 1967

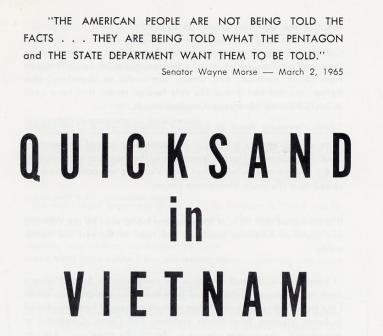

By early 1965, convinced that the United States government was the primary obstacle to initiating a cease-fire and subsequent negotiations in Vietnam, Linus Pauling increasingly began to go on the offensive against the war.

In February, he delivered a major public address at the Pacem in Terris convocation, which was held in New York City, stating that, for thousands of years, throughout “the entire period for which we have historical knowledge,” war was one of the principal causes of human suffering. “I believe that we have now reached the time in the course of the evolution of civilization when war must be abolished from the world,” Pauling thundered from the podium. Armed conflict must be replaced by a system of world law, he added, one “based upon the principles of justice and morality.”

Pauling returned to New York in March to participate in a peace parade and rally, walking with fellow protesters from 5th Avenue to the Central Park mall, where he delivered another speech decrying the war as both immoral and illegal.

Dean Rusk

Developments in Vietnam made it increasingly important that those who opposed the war speak out forcefully. By the summer of 1965, the American ground war had been authorized by President Johnson, an action that marked a profound departure from the administration’s previous insistence that the government of South Vietnam bear the responsibility for defeating the National Liberation Front (NLF). Due to continued losses by and falling enrollment within the army of South Vietnam, U.S. ground troops were deployed in a new strategy that had now switched from defensive to offensive.

This drastic change was deemed necessary as the NLF was seen by U.S. officials, including Secretary of State Dean Rusk, as a front for North Vietnamese hostilities and nothing more. Moreover, the the North’s aggression was not meant to unify the nation under a democratic regime, but represented instead a policy of communist expansion that enjoyed at least tacit support from China and Russia.

Rusk’s premise was one that Pauling had specifically rejected. In particular, Pauling pointed out that Rusk’s opinion on the plausibility of negotiations either distorted or, at times, ignored the actual position of the NLF, a stance that had been made clear in August 1965 and which made headlines in Europe, if not the United States.

The crucial detail that the Rusk and the American media had failed to communicate was that the NLF’s Five Point Declaration – a document based on the four-point plan that Ho Chi Minh had earlier communicated to Pauling and to the world – did not stipulate that U.S. troops be withdrawn as a precondition to negotiations. In fact, it called only for a freeze in the build-up of American troops, for a concurrent cease-fire, and for American agreement that the NLF to be brought to the negotiating table as a direct party or state entity. The NLF’s end goal for any ensuing negotiations would be a return to the 1954 Geneva Accord, an agreement that Washington had once purported to support as well.

The failure to act on or even move toward this opportunity was, for Pauling, a clear indication that the United States was not interested in ending the conflict. In December, Pauling wrote a statement to this effect, which was divided into two parts and aired on WPTR radio in Albany, New York. In the broadcast, Pauling reiterated these beliefs in an attempt to correct the broad American assumption that the North Vietnamese were not inclined to enter negotiations.

McGeorge Bundy

Prior to 1965, some of the most prominent academics commenting on the war were doing so in support of the war effort. Among them were McGeorge Bundy, William Bundy and W.W. Rostow, each of whom was an academic who held a position of influence on foreign policy in Vietnam. With the deployment of American troops in 1965, an equal and opposite cohort of thinkers had coalesced, and Pauling got the idea of calling for a meeting between representatives of this group, of which he was a part, and the Bundy group.

Pauling’s argument against the Bundy point of view was that a war could not be fought without clear enemies and allies. Assuming this, and based on the United States’ stated policy as well as the targets that it had already struck, it was unclear how enemy was being discriminated from ally. Indeed, insurgent groups were being attacked at undisclosed targets in not only South Vietnam, but also North Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, a fact that was largely hidden from public view in the United States.

Likewise, the United States was increasingly acting as a lone military force: though Washington encouraged its allies to contribute troops, and while Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, Thailand, and the Philippines had all agreed to do so, major allies including Canada and the United Kingdom had declined the request

Meanwhile, the political situation in South Vietnam was becoming increasingly unstable. Air Marshal Nguyen Cao Ky and a figurehead Chief of State, General Nguyen Van Thieu, had risen to power following the assassination of President Diem and a series of internal coups that followed. Further complicating matters was the face that war in Vietnam was never declared, and Pauling argued forcefully that, as such, American military action continued to be undertaken, in effect, unconstitutionally.

The issue of legality extended to international law as well, with the U.S. acting in apparent violation of the charter of the United Nations, which required members to refrain from the use of force until all attempts to settle a dispute were exhausted. Likewise, the Geneva Conventions of 1949, which defined crimes against humanity, and the Geneva Accords of 1954 all seemed to have been violated by the United States’ entry into the conflict.

Pauling’s position against the war was encapsulated in a a personal letter that he sent to McGregor Bundy in April 1965. If the real reason that a cease-fire was not possible was the communist aspiration for victory by force, Pauling asked, then would the United States in fact support free elections in Vietnam even if doing so resulted in a democratically elected and unified communist Vietnam?

If an answer came, it does not remain extant. Regardless, by the middle of the 1960s, Pauling had increasingly come to agree with the point of view that the war in Vietnam was principally being fought to contain communism and to protect American economic interests.

If this were true, then the American government, under both Kennedy and Johnson, had deliberately misled the American people – a suspicion that was confirmed for Americans in 1971 with the unsanctioned release of the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times. Pauling’s shifting perspective and his increasingly vocal activities during this time displayed his growing lack of confidence in his country’s leadership, another example of the broken trust that many other Americans were feeling as the 1960s moved forward.