Korean 801

Korean Air 801 was a Boeing 747-300 that departed Seoul, South Korea en-route to the island of Guam, a US territory in the western Pacific Ocean.

After an otherwise uneventful trip, flight 801 approached Guam at around 1:30am on the 6th of August, 1997. With a clearance to execute the instrument approach to runway 6L at the Antonio B. Won Pat International Airport, flight 801 contacted the control tower for a landing clearance…but the flight never reached the airport. Confusion ensued as the tower and approach controllers attempted to ascertain the location of the missing Boeing 747. It took an hour for rescue teams to reach the crash site.

Korean Air 801 descended into Nimitz Hill about 3 miles short of the airport. There were 2 pilots, 1 flight engineer, 14 flight attendants and 237 passengers on board at the time of the accident...only 26 people survived.

Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT)

Controlled Flight Into Terrain, or CFIT, is a term used to describe an accident in which an airworthy aircraft is unintentionally flown into the ground, water or any other obstacle while under positive pilot control. According to Boeing, CFIT accidents have accounted for more than 9,000 deaths since the early beginnings of the commercial jet age.

There are a number reasons why a competent, properly trained and skilled pilot might fly a perfectly good airplane into the ground. Fatigue, disorientation, loss of situational awareness and distractions like minor equipment malfunctions and poor weather are among the leading causes…unfortunately, pilot error ranks high on the list of causal factors in CFIT accidents.

As with any accident, there was a chain of events that led to the crash of Korean Air 801. Each and every one of the potential causes listed above was present in one form or another. Together, each served as a link in the chain…the removal of any one link could very likely have saved the lives of the 228 people who perished on Nimitz Hill on that dark and stormy night.

Link...Fatigue

CVR recordings confirm that the cockpit crew was tired. Flight 801 was originally scheduled to be operated by an Airbus A300, but the airline later planned to utilize a Boeing 747-300 to provide more seating as the flight was chartered to transport Guamanian athletes to the South Pacific Mini Games in American Samoa.

Captain Park Yong-chul began a scheduled round trip to Hong Kong three days before the accident, but his return flight was delayed due to inclement weather. As a result, he was forced to remain overnight in Hong Kong and pilot another 747 back to Seoul the next day. The captain was not originally scheduled to fly to Guam that night. He was initially scheduled to fly to Dubai, United Arab Emirates; however, as a result of his late arrival from Hong Kong, he didn't have adequate rest for that trip and was reassigned the shorter trip to Guam.

This is all significant because the captain at the controls that night had been working a daytime schedule in the days before the accident. His wife also testified that his normal routine was to wake between 0600 and 0630 and that he normally went to bed around 2300. She reported that he awoke at 0600 on the day of the accident…the scheduled arrival into Guam was well after midnight.

The CVR recorded the captain making several remarks related to crew scheduling and rest issues. He was heard commenting that "they make us work to maximum" and commented numerous times about being sleepy.

Ironically, many pilots find it especially difficult to be fully rested for the first day of a trip. Many pilots, me included, have busy home lives. Kids need to be escorted from here to there…bills need to be paid…the lawn needs to be mowed…whatever the cause, a pilot’s home life often results in a less than restful night’s sleep the day before a trip…especially one that requires the pilot to work outside his normal sleep pattern. This was certainly the case for Captain Park.

Link…Weather

I can tell you from experience that the desire to land after a long, tiresome day is a powerfully persuasive emotion. The accident occurred in the early hours of the morning after a long flight on the back side of the clock. The pilots were exhausted, in need of rest and the weather was going to be very close, if not below, the required minimums required to land. As they descended, the pilots got a quick glance of the island lights shining through breaks in the clouds that probably increased the expectation that they would be able to land at the airport. But as they descended on the approach, rain and clouds would decrease visibility at the airport enough to jeopardize the crew's ability to visually acquire the runway.

During most of the year in Guam, visual meteorological conditions (VMC) exist about 80 percent of the time, with instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) seen mainly during the afternoon hours when thunderstorms and rain showers are common. The crash of Korean 801 occurred in August, in the heart of the rainy season when precipitation averages about 24 days per month. However, even during the rainy season, VMC conditions typically prevail during the nighttime hours. The weather conditions encountered by the crew of flight 801 on the evening of August 6, 1997 were unusual and unexpected.

The following terminal aerodrome forecast (TAF) was valid at the time of the accident:

“Wind 120° at 7 knots, visibility greater than 6 miles, scattered 1,600 feet scattered 4,000 feet scattered 8,000 feet overcast 30,000 feet. Temporary August 6, 0100 to August 6, 0600, wind 130° at 12 knots gusting 20 knots, visibility 3 miles, heavy rain shower, broken 1,500 feet cumulonimbus overcast 4,000 feet.”

Although weather was certainly a contributing factor and another link in the chain of events, in the end, it was not an inability to see the airport, but rather mistakes in the way the approach was flown that doomed flight 801.

Link…Equipment Malfunction

Captain Park had flown the approach over Nimitz Hill 9 times during his career, but there was a major difference this time. The normal approach to runway 6L at Guam is an ILS approach in which guidance is provided for both lateral and vertical navigation, but at the time of the accident, the glide slope beacon had been removed for scheduled maintenance. During this time, the lateral navigation capabilities of the approach were still in service, but pilots would be required to fly a non-precision approach requiring a stair step descent to the runway. This was the same situation that the Asiana 214 crew experienced in San Francisco.

All instrument rated pilots are trained to fly such approaches, but the reality in most parts of the world is that we rarely fly them. As a domestic pilot flying into large US cities, I could easily go a year without flying a single non-precision approach. I get plenty of practice during yearly recurrent training cycles, but precision ILS approaches are definitely the norm.

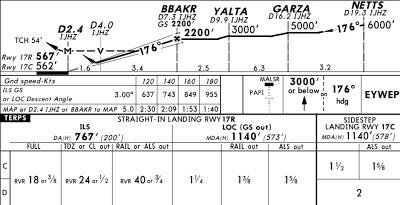

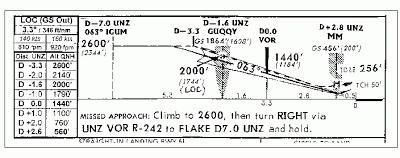

Given the avionics equipment available to the pilots of Korean 801, the pilots were required to descend at short intervals based on distance from the airport. I've posted an example from another approach below. In this example, the pilot would maintain 6,000 feet until reaching a point 19.3 miles from the airport. Reaching 19.3 miles, the pilot would descend to 5,000 feet and maintain that altitude until reaching a point 16.2 miles from the airport. At 16.2 miles the pilot would descend to 3,000. At 9.9 miles the pilot would descend to 2,200 and at 7.3 miles he would descend at a rate based on his ground speed to reach the end of the runway at an altitude that would allow a normal landing. It’s actually pretty simple, but it adds to the complexity of the procedure.

.

.

Each step down altitude is designed to get the airplane closer to the ground while providing safe terrain and obstacle clearance. If the pilot descended too soon at any point on the approach, it would be very easy to impact the ground well before reaching the airport.

Link…Pilot Error, Situational Awareness and Disorientation

4 months before the accident, 42-year old Captain Park Yong-chul received a flight safety award from the company president for the successful handling of a low altitude engine failure. He was a seasoned pilot with years of experience on the Boeing 747, held type ratings on the Boeing 747 and 727 and flew for the Republic of Korea Air Force. But as the NTSB began to look into flight training records at Korean Air, an alarming gap was discovered.

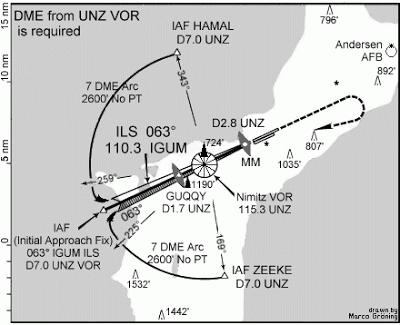

Distance Measuring Equipment, commonly referred to as DME, is what pilots use to determine distance from navigation beacons like the one used on the approach to Guam. In many cases, the source of DME is located at or near the end of the runway, so DME approaches zero as you approach the landing zone...but that isn't always the case and it wasn’t the case with the ILS to runway 6L at Guam.

In many, if not most cases, the DME signal for an ILS approach emanates from a point near the end of the runway and is displayed in the cockpit by selecting the ILS frequency. However, some ILS approaches are not equipped with DME capabilities…this was the case with the ILS to 6L. The picture below depicts the current day approach to Guam. Note that the DME signal to be used for the approach is not from the ILS, but from the NIMITZ VOR (UNZ) that sits approximately 3 miles from the runway and must be tuned separately. The VOR was the approximate impact point of Korean 801.

Keep in mind that the pilots would normally have flown a precision ILS approach to runway 6L…an approach with both lateral and vertical guidance that would lead the pilots all the way to the touchdown zone. It is entirely possible...in the heat of the moment...that the pilots might have forgotten that the DME was not co-located at the airport. The NTSB believes that fatigue and gaps in training and aeronautical knowledge led the crew to believe they had reached the approach end of the runway when DME reached zero.

Link…Extenuating Circumstances

First...the NTSB investigation report stated that the ATC Minimum Safe Altitude Warning (MSAW) system at Antonio B. Won Pat International Airport had been deliberately modified so as to limit nuisance alarms. As it was, the system could not detect an approaching aircraft below minimum safe altitude as it was designed to do. Instead of watching airplanes as they neared the airport, the system monitored traffic as it approached 50 miles from the airport…while the aircraft was still over the ocean. One level of safety was removed. If the system had been working, a low altitude warning would have sounded to alert air traffic controllers that the Boeing 747 was dangerous low and too close to terrain.

Second…and the final nail in the coffin for flight 801…was confusion regarding the status of the glideslope signal and a captain who chose to ignore subordinate crew member’s suggestions to go-around. Cockpit voice recordings indicate that the crew observed movement of the glideslope needle in the final minutes of flight that was interpreted as a usable glideslope signal. Exactly three minutes before impact, a back and forth conversation ensued regarding the indications they saw on the instrument panel.

Flight Engineer: "Is the glideslope working? Glideslope? Yeh?"

Captain: "Yes, yes, it's working."

Unidentified voice: "Check the glideslope if working?" "Why is it working?"

First officer: "Not useable."

Captain: “Isn't glideslope working?”

Ground Proximity Warning System (GPWS) standard callouts are recorded on the CVR.

“One thousand”

“Five hundred”

“Minimums, minimums”

The CVR then recorded the GPWS again as it called out several "sink rate" alerts that were followed by the first officer and flight engineer urging the captain to go-around.

"Two hundred "

"Let's make a missed approach."

“Not in sight!” “Not in sight!”

“Missed approach!”

“Go around!”

It was at that point that Captain Park finally called “go-around,” but the rate of nose-up control column deflection, which should have been around 3-4° per second, remained about 1° per second. The captain's response was literally too little, too late. “One hundred...fifty...forty...thirty...twenty..." The terrain was rising far faster than the aircraft as its high bypass turbofan engine struggled to spool up. The aircraft impacted Nimitz Hill less than three seconds later.

It is believed that Captain Park fixated on the glideslope which he believed to be working. Instead of a stair step descent as depicted on the approach chart, flight 801’s final descent was a slow, steady and controlled descent into terrain at the approximate point where DME would have indicated zero.

Hierarchical stratification of Korean society and authority is considered a factor in why concerns about a failed approach were not heeded by the captain.

Similarities to Asiana 214?

As I stated before, all three posts in this series are in response to the July 6th crash of Asiana 214, but none is intended to be a definitive explanation of that accident. I believe strongly in learning from our mistakes. There are entire classes at most airlines designed to do just that...pick apart the mistakes made by other aviators and learn from them. As Sir Winston Churchill said, “Those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

With the crash in San Francisco fresh on my memory, I took this opportunity to remember three accidents from the not so distant past...BA38, Turkish 1951 and Korean 801. All three appear similar in nature to the Asiana crash and may hold clues to that investigation, but of the three, only Turkish 1951 bears striking similarities to Asian 214. Even so, we learn more from our mistakes than our success. I hope the discussion has provoked insightful consideration about the root causes of the accidents.

Be careful out there.