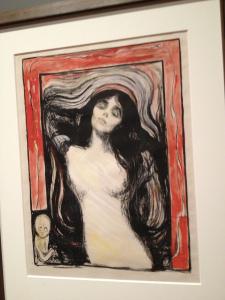

Among the paintings and prints in the Edvard Munch collection on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York is a rendition of his famous Madonna. I first saw a reproduction of this piece in a discussion of Christian art. The question, of course, was whether it could be considered Christian art or not. Munch was not known for creating religious-themed art. Angst was his more natural home. While not the only Madonna to pose naked, Munch predated the aging pop star by a fair number of decades, and named this piece after an icon of Catholic orthodoxy. The problem is the female body. Religion in the western world has pretty much always had difficulty dealing with embodiment. My generation grew up with Charlton Heston and any number of bare-chested, sculpted idols of manhood playing such characters as Tarzan, Ben-Hur, and Moses. Moses? Yes, even Cecil B. DeMille knew the draw of having a biblical hero bathed by a bunch of young, Egyptian women. We are used to seeing Jesus nearly naked on the cross—but Mary?

The issues tied to embodiment, although they effect every person who has a body, fall more heavily upon females. While there is little agreement as to the why, the excuse is often given that “man” is in the image of God and “woman” is derivative. In actual fact it seems more likely to me that men prefer an easy excuse for bad behavior. Biology sends a pretty strong reproductive message to most males, but, in the human realm at least, the larger burden rests with the females. By blaming the victims the male hierarchy—undeniable in the case of the church, as in many religions—insists that the female body is the problem. Males perform as God intended, thank you. But the reasoning is all backward here. Munch, if he intended this to be the Madonna, is problematizing the discourse.

Art, like holy writ, is open to interpretation. Munch did not explain his enigmatic Madonna, but like Leonardo da Vinci, lets the silent woman speak for herself. Scholars have long noted the multiplicity of Marys in Jesus’ life. At some points the Gospel writers leave a little too much inference up to the reader. It is pretty clear that Jesus had no trouble with women. But he was a singular visionary in a time when cheap blame was easily found. So Edvard Munch may have been following in the footsteps of the master when he portrayed the Madonna who accuses the world of double-dealing and false standards. It is an arresting artwork, and not for prurient reasons. What is being exposed here is a soul. She may be called the blessed virgin or the mother of God, but her gender is still castigated even by those who mouth such holy epithets. We may never know who Munch intended this to be, but we know she is every woman who has been repressed by the religion of men, yearning to be free.