I’ve just returned from a short trip to the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) in Bangalore, Karnataka, one of India’s elite biological research institutes.

Panorama of a forested landscape (Savandurga monolith in the background) just south of Bangalore, Karnataka (photo: CJA Bradshaw)

I was invited to give a series of seminars (you can see the titles here), and hopefully establish some new collaborations. My wonderful hosts, Deepa Agashe & Jayashree Ratnam, made sure I was busy meeting nearly everyone I could in ecology and evolution, and I’m happy to say that collaborations have begun. I also think NCBS will be a wonderful conduit for future students coming to Australia.

It was my first time visiting India1, and I admit that I had many preconceptions about the country that were probably unfounded. Don’t get me wrong — many of them were spot on, such as the glorious food (I particularly liked the southern India cuisine of dhosa, iddly & the various fruit-flavoured semolina concoctions), the insanity of urban traffic, the juxtaposition of extreme wealth and extreme poverty, and the politeness of Indian society (Indians have to be some of the politest people on the planet).

But where I probably was most at fault of making incorrect assumptions was regarding the state of India’s natural ecosystems, and in particular its native forests and grasslands.

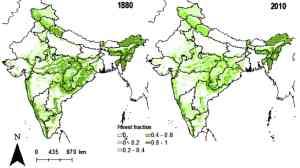

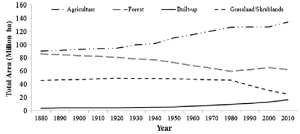

source: Tian et al. 2014 Global & Planetary Change 121:78-88

While preparing for my second (public) talk, I stumbled across an interesting paper that used a clever approach to integrate high-resolution satellite and inventory datasets to generate a time series of land-use change from 1880 to 2010 for the entire country of India.

What surprised me the most was just how little of India’s forests and grasslands had been destroyed. While it’s nothing to ignore — the country has lost 30% of its forests (89 to 63 million ha) and 44% of its grasslands since 1880 — for a country of such immense population pressure (excluding small and island states, India has the world’s 7th highest population density of 441 people/km2 in 2015), it’s rather remarkable that there’s any forest left at all, let alone 70% of what it had 135 years ago. In fact, India’s population has increased six-fold since 1880 (200 to 1200 million).

source: Tian et al. 2014 Global & Planetary Change 121:78-88

To compare, Australia has lost over 40% of its forest cover over the last 200 years, rain forests have declined by ~ 40% in Asia in the last 50 or so years, and the Amazon has lost 18% since only the 1970s.

The 52% expansion of croplands in India (92 to 140 million ha) have been the primary drivers of forest and grassland loss, but most of this occurred during the time when the British governed India, and during the early years of independence (post-1947 to the 1960s). After this time, several key pieces of government legislation vastly reduced the rates of natural habitat conversion (the 1952 National Forest Policy of India, the 1980 Forest Conservation Act, and the 1988 National Forest Policy). In fact, India now has a national target of 33% forest cover in plains areas, and 66% in hilly and mountainous areas to combat erosion and ecosystem degradation. Additionally, India invested heavily in reforestation from 1980-2010 (but not always with native species, mind you), such that the total area forest has actually risen from 1980 to 2010.

Of course, the human pressures in India are increasing, but I must tip my hat to the foresight of the governments over the last 30-50 years for embracing some environment protection (some corruption notwithstanding). India will have to be vigilant, because it holds some of the regions of highest biodiversity, such as the Western Ghats (a Biodiversity Hotspot), and it is the region of the world projected to have one of the highest population densities (> 650 people/km2) by 2100.

1I know! It really shouldn’t have taken me this long.

CJA Bradshaw