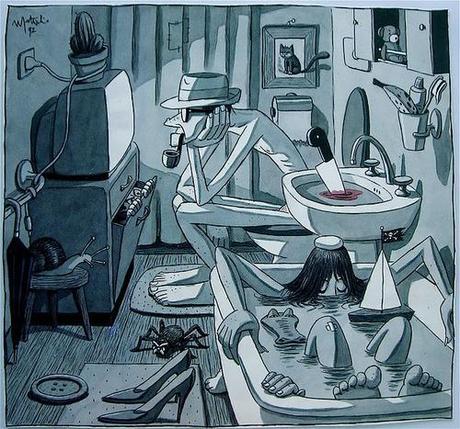

(Illustration: Franco Matticchio)

Rarely did Franco Matticchio—a talented illustrator from Varese who is a regular contributor to L’Indice and ViviMilano, as well as a cover artist for the publishing house Garzanti—give such proof of domestic claustrophobia as in this bathroom scene. A man is watching TV with a pipe and a Fedora hat, his long nose sharp and intrusive like the beak of a sad parrot, his thin shoulders raising from the toilet like a rusty hook; the woman sinking in the bathtub, alongside ominous and weird animals, is a miniature of ceremonious fear and coloristic virtuosity: her intensive gray juxtaposed against the leaky red spreading beneath the knife in the sink.

I described this illustration at some length because I am allowing myself to imagine that the old viewer is applying himself to a Juventus match, circa 2008 or 2009, at a time in which the club’s national affairs were administered by lawyers specially raised up by the Lord and there were fourteen judges, in a lapse of several mediocre coaches and overvalued players, who exercised in succession the office of chief magistrate. At that time, besides tributaries and slaves, the Juventus nation must have amounted to near twelve or fourteen million souls. Such black-and-white tribes, before they found a new king in a restless Agnelli pupil, formed separate republics, each having specific bounds, and each preserving its own chiefs and elders. (Their bloggers are never found without the insignia of office or without proofs of affluence, combining the intimate and the monumental, the ceremonial and the everyday, Piedmontese curiosity and Southern anxiety—trying to subdue their countless adversaries with the stubborn zeal of the Israelites, perpetually unease that the Sidonians were never conquered and the Philistines, though for a time under their dominion, continued to be a distinct people until the days of Judas Maccabeus.)

Indeed, the Juventus blogger grew up to be a man of difficult character, to speak delicately. A proud fat man sprawled out in an armchair surrounded by his wife and children; hanging memories of Sivori, Platini or Zidane as stone portals leading to further splendors; the dullness of the present—like a noir d’ivoire in a Louvre portrait—inspiring spite and discomfort; the background behind the couch becoming an undifferentiated and sonorous canvas of swearing; irregular stripes of deep juicy browns leaking from the perpendicular axis of Chiellini’s gung ho defending. . .

The Juventus tribes have always been, however nomadic, very international—their unrivaled presence in the U.S., a wordly reward for the industriousness of the club’s founding fathers. Overtime, they formed a bond of union, which united them into one federal State: the worship of Luciano Moggi. With few exceptions (I among them) every ordinary supporter dreamed of reliving Moggi’s heroic age, when even the markedly corpulent players, like Alen Bokšić, could move with an almost dancelike grace, and the Director’s psychological inquisitiveness seemed to border on prophesying.

Terboch, The Flea-Catcher, circa 1655 (Munich, Alte Pinakothek)

Despite his later desire to create a whole gallery of similar works, as in a painting within a painting, Moggi entered soccer history as a painter of genre themes and a portraitist. He practiced his craft with success, most likely owing much to contacts made across the Alps, during the numerous and quiet trips of a textile merchant from Haarlem. (Moggi acknowledged only closed, delimited spaces.) He delayed his deals, was fussy, grumbled, and he considered that the sum of 500 guldens, for any of his players, was decidedly too low for a transfer. He needed at least four months to execute a picture, and when he was so busy that he had to put aside other urgent orders, he played the part of the concentrated boy who is studying the secrets of arithmetic. No contemporary painters, and few of their descendants, possessed to such a degree a business acumen based on two firm principles: never to go below the honorarium designated by the painter, and to value yourself highly in order to be valued by others. Moggi was an unsurpassed painter of coalescing young footballers (his office swarmed with models). The majority of managers painted players as chubby cherubs, or dolls clothed in costumes modeled on the functional design of some formations, creatures deprived of their own life and personality—chrysalides looking at us with idiotic expression, or larvae, unfinished dwarfish forms of soccer species. Yet Moggi, his smoking fingers moving along the skin of the footballing animals, secured success in the profession, enclosing with the player also clothes, long and short brushes, paper, chalk, and all the beautiful paints of the craft.

Be it idolatry or the transmission of Moggi’s ordinances to posterity, in consequence of his sins, Juventus supporters were long since driven through a footballing Desert of Paran, the rugged 1-1 draw with Rimini a new Isthmus of Mount Sinai, an occupied Jericho, where black-and-white Levi and Joseph had experienced the membranaceous time of the Canaanites. ♦