In this series thus far, I have discussed the ways in which Edgar Allan Poe is perhaps best viewed as a literary prankster or practical joker. In Part 1, I argued that the great theorist of “Diddling Considered as One of the Exact Sciences” was also, in his various works, a master “diddler,” frequently putting one over on his readers. In Part 2, I discussed the “poet as prankster,” suggesting that even Poe’s poetry is not always as serious as it seems, while examining one poem (“O Tempora! O Mores!”) that was itself composed and presented as part of an elaborate practical joke. In Part 3, I argued that many of Poe’s most well-known stories, which are usually read as Gothic horror or mystery, might be considered as humorous, frequently functioning as comical send-ups of popular fictions of the era. In this entry, I want to consider another genre of writing for which Poe was quite famous in his own time: literary criticism. Not surprisingly, Poe’s literary criticism bears the mark of the prankster’s spirit, as his book reviews and essays are often filled with sardonic humor.

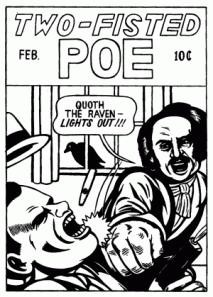

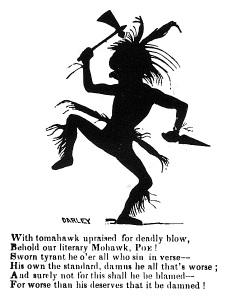

As a literary critic and book reviewer for a number of magazines, Poe developed an infamous reputation as a “tomahawk-man,” a harsh critic who, in the words of his great contemporary James Russell Lowell, “seems sometimes to mistake his phial of prussic-acid for his inkstand.” Lowell’s own humorous aside does not detract from his judgement, stated one line earlier, of Poe as “the most discriminating, philosophical, and fearless critic upon imaginative works who has written in America.” Perhaps because of this discriminating, philosophical fearlessness, Poe-the-critic was loathe to suffer fools gladly or even at all, and some of his best known zingers have come at the expense of his fellow poets and fiction writers.

As a literary critic and book reviewer for a number of magazines, Poe developed an infamous reputation as a “tomahawk-man,” a harsh critic who, in the words of his great contemporary James Russell Lowell, “seems sometimes to mistake his phial of prussic-acid for his inkstand.” Lowell’s own humorous aside does not detract from his judgement, stated one line earlier, of Poe as “the most discriminating, philosophical, and fearless critic upon imaginative works who has written in America.” Perhaps because of this discriminating, philosophical fearlessness, Poe-the-critic was loathe to suffer fools gladly or even at all, and some of his best known zingers have come at the expense of his fellow poets and fiction writers.

For example, in an 1843 review of William Ellery Channing’s Our Amateur Poets, Poe writes: “His book contains about sixty-three things, which he calls poems, and which he no doubt seriously supposes so to be. They are full of all kinds of mistakes, of which the most important is that of their having been printed at all.” A paragraph later he calls for the author to be hanged, but—out of deference to his good name (Channing Sr. having been a “great essayist”)—Poe urges that the hangman “observe every species of decorum, and be especially careful of his feelings, and hang him gingerly and gracefully, with a silken cord.” Presumably, the remainder of the book review represents that figurative execution.

Poe’s criticism bristles with humor, often in its more “malevolent” form as sarcasm. As I point out in my book, Poe and the Subversion of American Literature: Satire, Fantasy, Critique, this sense of humor is part of Poe’s literary theory. Humor is connected to his more “serious” philosophy of the imagination, the faculty of the human mind most exalted by the Romantics. In a note to essay on Nathaniel Parker Willis in his New York Literati series, Poe asserts that the “Imagination, fancy, fantasy and humour, have in common the elements combination and novelty.” Not surprisingly for a writer who so admired Coleridge and Byron, Poe goes on to explain that “The imagination is the artist of the four. From novel arrangements of old forms which present themselves to it, it selects such only as are harmonious; the result, of course, is beauty itself—using the word in its most extended sense and as inclusive of the sublime.” The others (fancy, fantasy, and humor) operate by selecting inharmonious elements, which would normally offend the higher sensibilities of the gentle reader; but, in certain circumstances, such fanciful, fantastic, or humorous arrangements can offer real delights. As Poe reveals, the more outlandish the skillful ordering of cacophonous or incongruous parts, the closer one approaches a form of pleasurable excess to be found in works of humor, as the absurdity of the scene goes from seeming merely erroneous or eccentric to being pretty funny.

Consistent with my view of Poe as a prankster or practical joker, his theory of fanciful, fantastic, or humorous literary combinations—that is, those that cannot achieve the supernal beauty of the most well-wrought works of the imagination—leads him to consider the more pointed use of humor in the service of critique. “The four faculties in question seem to me all of their class; but when either fancy or humor is expressed to gain an end, is pointed at a purpose—whenever either becomes objective in place of subjective, then it becomes, also, pure wit or sarcasm, just as the purpose is benevolent or malevolent.” That is, when humor is not simply intended to elicit a smile or a laugh, but it also used to serve some ulterior aim, it can become a forceful kind of criticism in its own right.

Poe’s theory of humor therefore applies not only to creative writing, fiction and poetry, but also to his nonfiction essays and reviews. At the time, not everyone agreed that humor belonged in literary criticism. In a letter to Beverley Tucker in 1835, Poe responds to Tucker’s complaint that humor has no place such writing. As Poe explains,

The distinction you make between levity, and wit or humor (that which produces a smile) I perfectly understand; but that levity is unbecoming the chair of the critic, must be taken, I think, cum grano salis. Moreover — are you sure Jeffrey was never jocular or frivolous in his critical opinions? I think I can call to mind some instances of the purest grotesque in his Reviews — downright horse-laughter. Did you ever see a critique in Blackwood’s Mag: upon an Epic Poem by a cockney tailor? Its chief witticisms were aimed not at the poem, but at the goose, and bandy legs of the author, and the notice ended, after innumerable oddities in — “ha! ha! ha! — he! he! he! — hi! hi! hi! — ho! ho! ho! — hu! hu! hu”! Yet it was, without exception, the most annihilating, and altogether the most effective Review I remember to have read.

Poe’s point is that criticism, like the literature it is duty-bound to analyze and evaluate, sometimes needs to be humorous. In fact, for Poe, certain types of work under consideration by the critic positively demand humorous, witty, or sarcastic treatment. Referring to the same remembered review from Blackwood’s, Poe “cannot help thinking levity here was indispensable. Indeed how otherwise the subject could have been treated I do not perceive. To treat a tailor’s Epic seriously, (and such an Epic too!) would have defeated the ends of the critic, in weakening his own authority by making himself ridiculous.” In his own criticism, as in his poetry and tales, Poe issues forth this “horse-laughter,” and his often ferocious mirthfulness brings together the fantastic and satirical elements of his overall literary and critical project.

To avoid laughter in one’s criticism for the sake of propriety is to recuse oneself from criticism entirely, Poe seems to suggest. To suffer fools too gladly is to reveal one’s own foolishness. And although Poe was not entirely consistent or fair in his treatment of contemporary poets and writers, as this 1848 caricature not so subtly lampoons, he was not often willing the play the fool himself.

[coming soon, Joker Poe, Part 5: The Jingle Man]

© 2014 Robert T. Tally Jr.

Robert T. Tally Jr. is an associate professor of English at Texas State University. His books include Fredric Jameson: The Project of Dialectical Criticism; Poe and the Subversion of American Literature; Spatiality (The New Critical Idiom); Utopia in the Age of Globalization; Kurt Vonnegut and the American Novel; Melville, Mapping and Globalization; and, as editor, Geocritical Explorations; Kurt Vonnegut: Critical Insights; and Literary Cartographies. Tally is also the general editor of Geocriticism and Spatial Literary Studies, a Palgrave Macmillan book series.