In earlier posts, I have mentioned that when we think about Southwestern humor, three or four authors come to mind out of the thirty or forty who were actively writing at the time. Johnson J. Hooper is one of these three or four, classified as "The Big Bear School" of sketch writers from the 1830s-40s. In classifying Hooper this way, scholars such as M. Thomas Inge, Walter Blair, and Franklin J. Meine defined the school as authors who used the regional vernacular speech, letting the characters speak for themselves. In addition, the authors used a content set of tales that included the fact that they were con men of sorts, and the stories often described horse races and swaps, camp meetings, swindles, and generally bilking both the common people and the politicians alike. Often the tales deflate the egos of those who believe themselves smarter or more moral than the less educated back country population. They receive their comeuppance in the tales by being outsmarted by the main character. Hooper's recurring character is Captain Simon Suggs, late of Tallapoosa County.

In earlier posts, I have mentioned that when we think about Southwestern humor, three or four authors come to mind out of the thirty or forty who were actively writing at the time. Johnson J. Hooper is one of these three or four, classified as "The Big Bear School" of sketch writers from the 1830s-40s. In classifying Hooper this way, scholars such as M. Thomas Inge, Walter Blair, and Franklin J. Meine defined the school as authors who used the regional vernacular speech, letting the characters speak for themselves. In addition, the authors used a content set of tales that included the fact that they were con men of sorts, and the stories often described horse races and swaps, camp meetings, swindles, and generally bilking both the common people and the politicians alike. Often the tales deflate the egos of those who believe themselves smarter or more moral than the less educated back country population. They receive their comeuppance in the tales by being outsmarted by the main character. Hooper's recurring character is Captain Simon Suggs, late of Tallapoosa County.

Although Hooper fits this definition in the content of most of his sketches, in other important stylistic ways his differ from the "standard" Southwestern sketch-specifically, he uses much more exposition and much less dialog than other authors from this "school" like George Washington Harris (the Sut Lovingood tales) and Thomas Bangs Thorpe ("The Big Bear of Arkansas"). I would like to suggest that Hooper does so based upon his own personal understanding of what good writing ought to be for a Southern gentleman.

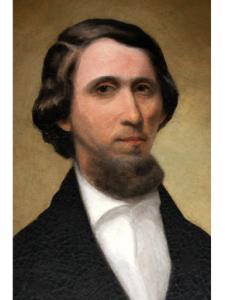

That Hooper was such a gentleman is evidenced by his upbringing in pre-Civil War Georgia. He is one of the earliest of this type of yarnspinning along with Augustus Baldwin Longstreet ( Georgia Scenes) and William Tappan Thompson (the Major Jones stories). His great grand uncle was a Boston minister and one of the original signers of the Declaration of Independence. His family were early emigrants to Georgia territory; His father brought the family to Georgia, where Johnson was born and raised. His father was a literary man, but not, unfortunately, a businessman; thus Hooper, as the third in a line of sons, grew up in more straightened circumstances than his older brothers. He inherited his father's love of literature and writing, but not much else. In his lifetime, Hooper was an author, an editor for several newspapers, and a historian of the politics of the Southern cause before and during the Civil War. His Simon Suggs stories were early writings in his career, used as fillers for his newspaper editions, but became very popular, and were later published in both the Spirit of the times and as a collection of short tales.

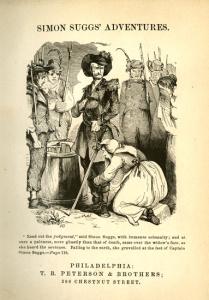

Like many of the Southwestern humorists, Hooper first published his work in William T. Porter's Spirit of the Times. Porter was instrumental in helping Southwestern humorists like Thorpe, Harris, and Hooper gain national attention both through the magazine and through his two collections of work from the Spirit in The Big Bear of Arkansas and Other Stories and A Quarter Race in Kentucky. In this capacity, Porter was instrumental in negotiating the collected works, Some Adventures of Captain Simon Suggs, Late of the Tallapoosa Volunteers: Together with "Taking the Census" and Other Alabama Sketches, for Hooper, which was published in 1845.

Generally, those authors most closely associated with the Big Bear School follow Wayne C. Booth's (much later) description in The Rhetoric of Fiction. They "show" rather than "tell"-that is, they contain much more dialog than description. The characters do the talking, and the reader is left to interpret what the characters say. For example, in the tales of Sut Lovingood penned by George Washington Harris, a reader will find one or two short paragraphs at the beginning of the sketches by a narrator (Sut's friend, George), setting up for the oral story then told by Sut himself in dialect. The sketches may also contain a final sentence or two by that narrator, thus framing the tale on both ends.

By contrast, Hooper's stories and sketches contain much more description of place, time and situation, with correspondingly less dialect, primarily in the form of quotations of Simon's speech. Harris's choice to let Sut tell his story creates the effect of a raconteur, a good storyteller, presenting an oral tale. Hooper's choice to tell most of the story as an unnamed narrator creates a very different effect-that of a well-educated gentleman telling a story he has heard, occasionally letting Simon speak so that the reader gets the "flavor" of Suggs's speech. This separates the author from the speech of the sketch, demonstrating for the reader the difference between author and character. This would be important to an educated Southern author from a "good" family, who would have been expected to write erudite prose.

A sample taken from "Simon Fights 'the Tiger' and Gets Whipped-But Comes Out Not Much the 'Worse for Wear'" should demonstrate this stylistic difference and its effect. The reader will notice that "the tiger" (in this case, referring to games of chance) and "the worse for wear" are both offset by quotation marks, by which the author indicates that they are slang. Simon himself uses slang terms more often than not, but does not bother indicating that the words are such, as that is his natural form of speech and he does not distinguish them from "proper" English.

In setting the stage for the story, the author begins with two long paragraphs showing where Simon is and what he is doing:

"As a matter of course, the first thing that engaged the attention of Captain Suggs upon his arrival in Tuskaloosa, was his proposed attack upon his enemy. Indeed, he scarcely allowed himself time to bolt, without mastication, the excellent supper served to him at Duffie's, ere he outsallied to engage the adversary."

Word and phrase choices such as "engaged the attention", "mastication", and "outsallied" are choices that would be foreign to Simon himself, but demonstrate that the author's vocabulary is an elevated and educated one. The description takes up two paragraphs. Anywhere within it necessitating slang always sees it appear in quotation marks:

"As he hurried along, however, hardly turning his head, and to all appearance, oblivious altogether of things external, he held occasional "confabs" with himself in regard to the unusual objects which surrounded him..."

When Simon does speak, the contrast between himself and the narrator is striking:

"Well, thar's the most deffrunt sperrets in that grocery ever I seed! Thar's koniac, and old peach, and rectified, and lots I can't tell thar names! That light yaller bottle tho', in the corner thar, that's Tennessee! I'd know that any whar! " (italics Hooper's)

The sketch goes on to detail Simon's encounter at a tavern in which he is soundly beaten at cards, loses all of his money, and manages to get one of the spectators to bankroll him-in the process gaining back more cash than he started out the evening with.

Is some ways, the contrast itself between Hooper's narrator and Simon Suggs creates its own brand of humor. Readers, more educated than Simon, find his manner of speech alone funny. However, the more interesting question for scholars is why Hooper was not content to allow Suggs to speak entirely for himself as did many other authors from this School, in this time and place. I argue that this inability to leave Simon to his own devices, which would be much more realistic, derives from Hooper's desire to be known as an educated author. For a Southern gentleman, writing was a major part of demonstrating one's erudition to the public. Joseph Glover Baldwin, another Southwestern humorist less well known today, sums this philosophy up in a letter to his son, Sandy in 1855 :

"Write in a clear, vigorous, pointed style, natural and easy; always say common things in a common way: study to be clear-have a definite meaning in your mind and represent it in your words....Avoid all exaggeration. Rise to the subject-but don't go beyond it. Overstatement very generally is worse than understatement. Don't strain after wit. Quiet is best. Uproarious bizarre humor is not quite the style of a gentleman or a scholar. The best speaking and writing is strung sense with the point of wit on it: Like an axe made of iron with the edge steeled. "

While it might be fine for Hooper's country bumpkin storyteller to use slang, over-exaggeration, and belaboring of a point, the author himself, as a gentleman, should never do so. The fact that Hooper was mindful of his reputation is made clear later in his life. His fame, much like Baldwin's own fame for Flush Times in Alabama and Mississippi, was based upon his Simon Suggs sketches, while his essays, political opinions, and journalistic writing were less popular then, and relatively unheard of today. So much so, in fact, that when Hooper made appearances anywhere, he was often referred to as "alias Simon Suggs." At the 1860 June Democratic Convention, which Hooper attended both as journalist and as a Southern Rights Democrat, word went around on the floor that the author of Simon Suggs was present, and the call went out for "Suggs" to come forward. Hooper refused to acknowledge this call. Much like Mark Twain, who in later years was embarrassed by his early story, "The Notorious Jumping Frog of Calavaras County," Hooper preferred to be known for his non-humorous writing.

The moral of the story, for Southern gentlemen of the nineteenth century, at least, appears to be that it is all well and good for a man to write humorous sketches and stories for the entertainment of other refined Southern gentlemen; however, the "proper" texts for a gentleman are history, essays, and hard-nosed journalism-not humor.*Quotations from the sketch, "Simon Fights 'The Tiger'" are taken from Adventures of Captain Simon Suggs, M.E. Bradford, ed. Nashville, TN: J.S. Sanders and Co., 1993. The original edition was published in 1845 by Carey and Hart.

Janice McIntire-Strasburg

Saint Louis University

Notes:

*Quotations from the sketch, "Simon Fights 'The Tiger'" are taken from Adventures of Captain Simon Suggs, M.E. Bradford, ed. Nashville, TN: J.S. Sanders and Co., 1993. The original edition was published in 1845 by Carey and Hart.

*Baldwin's advice on good writing to his son, Sandy, is taken from a letter Baldwin wrote to him on 22 February, 1855

*The biographical information given here is summarized from Alias Simon Suggs: A Biography of Johnson Jones Hooper, Hoole, Stanley, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, Publishers, 1970.