Rue Gît le Coeur: street where lies the heart. On a tiny street in Paris, about a quarter of the length of a New York City block and just a little wider than a Venice passageway, lies a minuscule hotel. Its rooms, replete with medieval-era wooden beams and matching pastoral designs on the wallpaper and curtains, are just as tiny; only one person can move around in the room at a time. The elevator, too, can manage only one person per trip. Charming and minute, there is no space in this hotel for oversized couches and exercise rooms; there is barely space enough to stretch out your arms and yawn, let alone sing.

When I visited this sequestered street last year—almost hidden in the midst of a crowded tourist district—I was amused and surprised to see the plaques, figured prominently on the hotel’s front façade, and the photographs displayed proudly in the lobby, honoring several Beat-era poets who had stayed there more than half a century ago. According to one of the plaques, William S. Burroughs supposedly wrote Naked Lunch there.

This hotel is to architecture what haiku is to literature: charming, ancient, and airtight—“no room for petty furniture,” as Emily Dickinson writes of compressed poetry. If there is a general view of Beat-era poetry, it is that it rides the force of Whitman’s barbaric yawp and delights in expansiveness, open vistas, and freedom. So it is a little unexpected and amusing to imagine multiple Beat poets writing productively in this very cozy, well-appointed hotel, just as there is something unexpected about the Beat poet who ventures into the space of haiku.

Jack Kerouac did not join his colleagues at this hotel, but he did spend considerable time within the small chamber of the haiku, testing its edges, poking fun at its purpose, and stumbling into very sweet encounters with its essence. Yet what stands out in his playful attempts with the form (which he renamed “Pop”) is their humor.

In his Book of Haikus, edited in 2003 by Regina Weinreich, Kerouac toys with nature. In the Japanese tradition of seventeenth-century poet Matsuo Basho, haiku juxtaposes something man-made with something from the natural world. Generally in Basho’s poetry, nature complements if not soothes loneliness.

Basho:

494.

drinking saké

without flowers or moon

one is alone.

(Matsuo Basho, The Complete Haiku, translated by Jane Reichhold (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 2008)

However, in Kerouac’s haiku, man and nature collide, confront one another, or fumble towards connection.

Kerouac:

A raindrop from

the roof

Fell in my beer

(New York: Penguin Poets, 2003), 30

Where Basho’s natural elements blend with or serve to illuminate the human situations in his haiku, Kerouac’s speakers sometimes come off as annoyed with nature.

Basho:

don’t be like me

even though we’re like the melon

split in two.

Nature is a not a metaphor in Kerouac’s haiku, but an encounter—even a clash:

Kerouac:

Bee, why are you

staring at me?

I’m not a flower!

(15)

The earth winked

at me—right

In the john

(10)

In his imitations of the Japanese model, Kerouac produces humor by reversing the direction of the metaphor: human experience is no longer compared to something beautiful in nature; rather, nature interferes with or is pitted against man-made entities.

Basho:

668.

even in Kyoto

longing for Kyoto

the cuckoo

Kerouac:

Run over by my lawnmower,

waiting for me to leave,

The frog

(33)

Kerouac’s speaker is in nature’s midst, and nature also crosses over into his domain. His speakers often use human measures to engage with nature:

Kerouac:

A bird on

the branch out there

—I waved

(33)

When the moon sinks

down to the power line,

I’ll go in.

(17)

Occasionally, he personifies nature, though his human vantage point, as a viewer in a car passing by along the American highway, for example, is vividly apparent in these examples:

Kerouac:

Grain elevators, waiting

For the road

To approach them

(7)

The windmills of

Oklahoma look

In every direction

(6)

Nodding against the wall,

the flowers

Sneeze

(10)

Sometimes nature succeeds in inspiring an almost surrealist burst of ecstasy for Kerouac, but Kerouac again inverts the formula; the ecstasy is not expressed through delight in nature but through delight in something manmade:

Basho:

778.

their color

whiter than peaches

a narcissus

Kerouac:

White roses with red

splashes—Oh

Vanilla ice cream cherry!

(40)

In the sun

the butterfly wings

Like a church window

(62)

In some haiku, Kerouac shows a picture of American life that is out of sink with nature; in others, nature is oblivious to the man-made world.

Kerouac:

August in Salinas—

Autumn leaves in

Clothing store displays

(41)

The sleeping moth—

he doesn’t know

The lamp’s turned up again.

(40)

Yet Kerouac does not exactly parody the form, even in these more comical examples. At times he uses its conventions with elegance, subtly embedding a seasonal clue within a tender or sensual image of everyday life.

Kerouac:

Evening coming—

The office girl

unloosing her scarf

(32)

The bottoms of my shoes

are clean

From walking in the rain

(7)

Elsewhere, Kerouac abandons imagery altogether and confronts the haiku form as a source of both frustration and fun in his philosophical meditation:

Kerouac:

Haiku, shmaiku, I cant

understand the intention

Of reality

(71)

Wild to sit on a haypile,

writing haikus,

Drinking wine

(70)

In the chair,

I decided to call Haiku

By the name of Pop

(63)

Do you know why my name is Jack?

Why?

That’s why.

(70)

Kerouac is well known as a funny author yet not always as a precise comic. He was, steadily, a public drunk, which, however understandably, unfairly sullies his reputation as a meticulous artist, suggesting a more chaotic, accidental humor.

In the above interview with William F. Buckley, a drunk Kerouac clearly states his aesthetic philosophy: “I believe in order, tenderness, and piety.” If we are surprised to hear this, Kerouac himself is partly responsible for that surprise; what he calls elsewhere in the interview his Dionysian way of life creates the impression of recklessness, making him, as his friend Allen Ginsberg explains in this follow-up interview, an unwelcome if misunderstood guest on Buckley’s show.

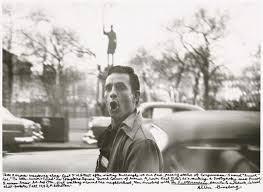

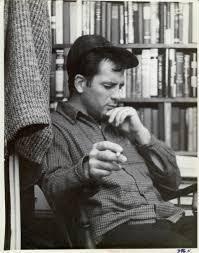

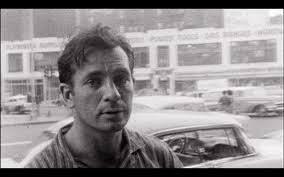

In these later years of Kerouac’s career, his outward exuberance seems to have been tinged with melancholy and exasperation. At a photography exhibit at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. several years ago, I was struck by the sadness in so many of the Kerouac portraits:

Yet if haiku derives force from the juxtaposition of incongruous elements, then Kerouac seems to have mastered its essence, embodying the weight of a true poet’s melancholy as well as a quality of silliness and humor, light as air.

Ezra Pound’s American haiku, most famous is his 1912 “In a Station of a Metro” based on the Paris metro, brings visual power to haiku in English but does not explore the form’s levity nor the bubbly, tender, and weird opportunities for humor through basic juxtaposition. Just as a few Beat poets once crowded into an elegant but row boat-sized hotel in Paris—just as Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Bookstore sits, juxtaposed, at a straight diagonal shot from a Franciscan holy site in San Francisco’s North Beach, so, too, the road-broadening Jack Kerouac honors the essence of haiku and goes one step further. In taking the metaphorical juxtaposition between man and nature literally, Kerouac uncovers humor in the form while maintaining order, tenderness, and his own special brand of piety. Thanks to Kerouac, we might say that humor is now an American stamp to the haiku form. In Kerouac’s hands, material items from ice cream to windmills are captured in a meditative light as they accidentally slipped into a the hand of a tender and wily philosopher.