It is one of my long-suffering ecological quests to demonstrate to the buffoons in government and industry that you can’t simply offset deforestation by planting another forest elsewhere. While it sounds attractive, like carbon offsetting or even water neutrality, you can’t recreate a perfectly functioning, resilient native forest no matter how hard you try.

It is one of my long-suffering ecological quests to demonstrate to the buffoons in government and industry that you can’t simply offset deforestation by planting another forest elsewhere. While it sounds attractive, like carbon offsetting or even water neutrality, you can’t recreate a perfectly functioning, resilient native forest no matter how hard you try.

I’m not for a moment suggesting that we shouldn’t reforest much of what we’ve already cut down over the last few centuries; reforestation is an essential element of any semblance of meaningful terrestrial ecological restoration. Indeed, without a major commitment to reforestation worldwide, the extinction crisis will continue to spiral out of control.

What I am concerned about, however, is that administrators continue to push for so-called ‘biodiversity offsets’ – clearing a forest patch here for some such development, while reforesting or even afforesting another degraded patch there. However, I’ve blogged before about studies, including some of my own, showing that one simply cannot replace primary forests in terms of biodiversity and long-term carbon storage. Now we can add resilience to that list.

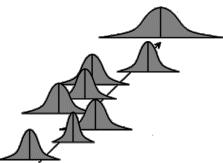

While I came across this paper a while ago, I’ve only found the time to blog about it now. Published in PLoS One in early December, the paper Does forest continuity enhance the resilience of trees to environmental change?1 by von Oheimb and colleagues shows clearly that German oak forests that had been untouched for over 100 years were more resilient to climate variation than forests planted since that time. I’ll let that little fact sink in for a moment …

While some of the statistics weren’t that flash, the result is beyond dispute. This adds a lot more weight to the argument that keeping primary forests intact is a far better strategy for ensuring the long-term resilience of biodiversity than attempting some half-arsed restoration that never quite hits the mark. The moral of the story is that we need to protect all remaining primary forest, and reforest the hell out of the vast swathes of deforested lands that now dominate our planet.

–

CJA Bradshaw

1Another little bugbear of mine – interrogative titles. Please, oh please, just tell us the answer and avoid patronising questions!