by the Earth First! Jaguar Team

Macho B, the last-known wild jaguar known to live in the U.S. until recent sightings, is shown in a snare in southern Arizona before his death in 2009.

In the world of big cat conservation, Dr. Alan Rabinowitz is a rock-star. He’s traveled the world, bushwhacking through the steaming jungles of Asia and South America, studying tigers and jaguars in an effort to protect them. He’s starred in documentaries by National Geographic, the BBC and PBS with titles like Lost Land of the Tiger, In Search of the Jaguar and Tiger Island. In 1984, he helped create the first jaguar preserve in the Western Hemisphere. Time magazine has called him the “Indiana Jones of Wildlife,” a title, according to friends and colleagues, which he savors.

So why then is Rabinowitz, founder and CEO of the wildcat conservation group Panthera, also one of the most outspoken critics of protected critical habitat for jaguars in the U.S. Southwest?

Strange Bedfellows

In 2012, following the efforts of numerous conservations groups, wildlife biologists, and other big-cat and jaguar experts, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service proposed more than 838,000 acres of habitat for federal protection, a full 11 mountain ranges through southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, for the American jaguar. The proposal has caused an uproar from ranchers and mining interests. Ranchers fear an increase in financial losses from cattle depredations–a fear that helped drive the jaguar to near extinction in the U.S in the first place–and the restrictions the designation would add to ranching use on public wildlands. Mining executives and financial investors of the proposed Rosemont copper mine in the Santa Rita Mountains southeast of Tucson–one of the mountain ranges in the jaguar habitat proposal–could see the hope of operations restricted to the point of nullification. For those who profit, the prospect of jaguars returning to the region means diminishing profits.

Automatic wildlife cameras snapped this photo of a male jaguar on a nightly walk in the Santa Rita Mountains on Oct 25, 2012.

Opponents of industrial use of public land in the Southwest see the jaguar as a rallying point: a mysterious, shy and spotted comrade in the fight against development. In southern Arizona its common to hear a group of rowdy and drunk redneck conservationists chanting “Viva, viva Macho B” in honor of what was once the last jaguar north of the militarized border.

Of the 150-plus comments the USFWS received on the jaguar habitat proposal, Rabinowitz offered the harshest criticisms, outstripping both ranchers and industry, arguing that it lacks scientific credibility and that Mexico and points further south make for better jaguar habitat.

The Arizona Game and Fish Department, the controversial state wildlife agency responsible for the death of Macho B in 2009–also agree with him, despite the fact that since then several jaguars have been observed on game cameras in Arizona. One was even spotted near the site of the proposed Rosemont mine, proof that they are coming to el norte.

In his comments Rabinowitz argued that, “The assumptions and speculations put forth in this document are, in my opinion, often incorrect and not in the best interests of either the jaguar or the people of the United States,” concluding in all capital letters, “THE UNITED STATES DOES NOT CONTAIN HABITAT THAT IS CRITICAL TO THE SURVIVAL OF THE JAGUAR AS A SPECIES! DESIGNATING CRITICAL HABITAT FOR THE JAGUAR IN THE UNITED STATES IS AN ABUSE OF THE TRUE INTENT OF THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT AND A WASTE OF U.S. TAXPAYER FUNDS.” A great deal can be read into a man who sides with industry and uses all caps in wingnut style to discredit the protection of a huge swath of land under constant threat of development. Maybe, as colleagues have said in a whisper, the guy is just a classic megalomaniac who is growing more and more out of touch with on the ground efforts to radically expand jaguar habitat. Perhaps he is profiting in some way. Perhaps its only a fool who looks for logic in the chambers of Rabinowitz’s heart. Its enough to realize that the former champion of jaguar protection is now solidly sided with those powers that would seek the jaguars total silence in the United States.

A Photo of Alan Rabinowitz

The list of those who disagree with Rabinowitz is large and includes several environmental groups–the Center for Biological Diversity, the Sky Island Alliance and the Wildlife Conservation Society, where Rabinowitz served as director of science and conservation before founding Panthera. Both the U.S. Forest Service and the National Park Service favor the proposal and have officially called for an expansion beyond the 838,000 acres.

Jaguars in the U.S.

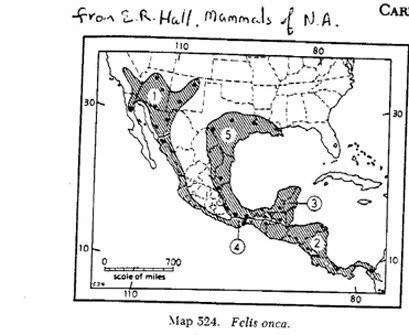

An earlier map of the historic occurrence of jaguars by the renowned mammologist E. Raymond Hall. Dr. Hall had demarcated 5 subspecies, thus the numbers on the map. Note: the overall area of occurrence for jaguar in Arizona and New Mexico is greater than the area in the nearby state of Sonora, Mexico.

Jaguars once roamed from South America through the southern and central United States, but lost habitat and were killed off in the east in the 1700s. They were reduced through Spanish bounties and fur hunting in the southwestern United States, and the last animals were systematically hunted down by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the 20th century, only to reappear sporadically due to migration from Mexico.

Much of the controversy around jaguar habitat in the U.S. Southwest, aside from industry fears at lost profits, revolves around the issue of breeding pairs. Rabinowitz maintains the assumption that jaguars observed in Arizona and New Mexico were and are still not residents of the United States or the region but rather dispersing transients (Rabinowitz 1999). However, evidence of this type of wandering dispersal has not been actually documented. This idea is further bolstered by several studies that contend that the northernmost breeding population of jaguars is concentrated at the confluence of the Aros, Bavispe, and Yaqui rivers, over 100 miles south of the U.S.-Mexico border (Lopez Gonzales and Brown 2002; Martinez-Mendoza 2000; Rosas-Rosas 2006). Some have pointed out that this evidence does not take into consideration the historical records of breeding populations in Arizona and New Mexico which demonstrate reproduction in the region occurring until at least 1910 (Brown 1983; Brown and Lopez Gonzalez 2001). Of the 61 historic records of jaguars in the United States from 1880 to 1995, sex was determined for only 25. Of those, 7 (28%) were females, and 3 (43%) of those were with young when killed. Thus, 12% of all known jaguars in Arizona were females raising young, clearly representing a breeding population north of the border (McCain and Chiles 2008).

Another contention rests in one of the biggest “debates” of our time: climate change. If Rabinowitz is correct, and jaguars in the Southwest are merely temporary residents, climate change may very well necessitate further ranging. According to Paul Beier of Northern Arizona University’s Forestry School, who also recognizes a historic breeding population in the region, it is plausible that parts of the U.S. could become critical in light of climate shifts.

Indiana Rabinowitz and the Last Crusade

Potential habitat for jaguars in Arizona and New Mexico, as determined by the Habitat Subcommittee of the Jaguar Conservation Team (2006). This map is based on records of past jaguar occurrence and habitat associations, surface water availability, absence of heavy agricultural or urban development, and other factors.

In the end Rabinowitz is walking a dangerous path when it comes to his reputation and the reputation of Panthera, his conservation organization. He has also put up the return of jaguars to the Southwest as his wager in this bet. In a recent interview, a self described “passionate and wealthy financial supporter of big cat conservation” who preferred to remain anonymous, summed it up this way: “I don’t support jaguar protection based on the nuances of petty debates. I am fully aware of the presence, both historical and current, of jaguars in the Southwest and that is enough for me. When I learned that Macho B was euthanized, I cried endlessly. Rabinowitz is vocalizing on the side of big industry here in Arizona and his words carry a lot of power. I can’t pretend to know why he is doing it, but in my mind he is on a crusade that will ensure breeding jaguars never return to this region.”

Its unclear why Rabinowitz is concerned that Endangered Species Act protections, and especially critical habitat designation, for jaguars in the U.S. will deter rather than enhance protection for the jaguar further south. The inter-connectivity of the northern states of Mexico to Arizona and New Mexico help create a much larger corridor for the jaguar, and could one day lead to a swath of protected habitat all the way down to Belize. Of all the battles that exist in the protection of big cats, Rabinowitz and Panthera have chosen to work against jaguar protection in the creatures’ northern reaches, a battle which can only result in unnecessary losses for the jaguar.

Please feel free to contact Panthera with your concerns at:

Panthera

8 West 40th Street, 18th Floor

New York, NY 10018

USA

Tel: +1 (646) 786 0400

Fax: +1 (646) 786 0401

Attn: Marla Kabashima

Office Manager, Panthera

[email protected]