Tracy Wuster

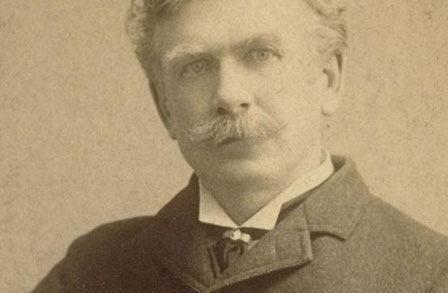

While Ambrose Bierce was considered, during his lifetime (and since), as an American humorists, he has been hard to fit into a general schema of American humor. Bierce doesn’t make it into Constance Rourke’s American Humor: A Study of National Character, maybe because he was opposed to the common man and the writer of dialect that figures so prominently in Rourke’s view of American humor. As Blair and Hill point out in America’s Humor, Bierce was a wit whose pen functioned as a scalpel often aimed at the common man and colloquial speech, presaging a movement toward wit and urbanity, toward alienation and fantasy, away from the native soil of 19th century humor. Interestingly, Bierce’s views on humor do not seem to have gotten much attention from humor studies scholars.

In The Devil’s Dictionary (1906), his attitude toward the humorist becomes clear:

HUMORIST, n. A plague that would have softened down the hoar austerity of Pharaoh’s heart and persuaded him to dismiss Israel with his best wishes, cat-quick.

Lo! the poor humorist, whose tortured mind

See jokes in crowds, though still to gloom inclined—

Whose simple appetite, untaught to stray,

His brains, renewed by night, consumes by day.

He thinks, admitted to an equal sty,

A graceful hog would bear his company.Alexander Poke

SATIRE, n. An obsolete kind of literary composition in which the vices and follies of the author’s enemies were expounded with imperfect tenderness. In this country satire never had more than a sickly and uncertain existence, for the soul of it is wit, wherein we are dolefully deficient, the humor that we mistake for it, like all humor, being tolerant and sympathetic. Moreover, although Americans are “endowed by their Creator” with abundant vice and folly, it is not generally known that these are reprehensible qualities, wherefore the satirist is popularly regarded as a soul-spirited knave, and his ever victim’s outcry for codefendants evokes a national assent.

Hail Satire! be thy praises ever sung

In the dead language of a mummy’s tongue,

For thou thyself art dead, and damned as well—

Thy spirit (usefully employed) in Hell.

Had it been such as consecrates the Bible

Thou hadst not perished by the law of libel.Barney Stims

WIT, n. The salt with which the American humorist spoils his intellectual cookery by leaving it out.

Bierce seems to have written sparsely about humor and wit directly in his voluminous writings. One piece, though, is of special note in the discussion of wit and humor. Published in The Collected Works of Ambrose Bierce, Vol. X: The Opinionator (1911), the essay “Wit and Humor” may have been a revision of “Concerning Wit and Humor” from the San Francisco Examiner (from either or both June 26, 1892 and March 23, 1903; 12).

His essay on “Wit and Humor,” obviously sides with the wit–not that there are any in America. Like many essays on humor in the nineteenth century (see Hazlitt or Lowell or Repplier, for examples) the distinction between wit and humor is central for Beirce, but unlike those others, Bierce is willing to more clearly distinguish between the two, and his essay is shorter and more readable than many. Interesting that the piece is not regularly, or so far as I can tell, ever reprinted in collections on humor. Enjoy

****

(98)

Wit and Humor

If without the faculty of observation one could acquire a thorough knowledge of literature, the art of literature, one would be astonished to learn “by report divine” how few professional writers can distinguish between one kind of writing and another. The difference between description and narration, that between a thought and a feeling, between poetry and verse, and so forth–all this is commonly imperfectly understood, even by most of those who work fairly well by intuition.

The ignorance of this sort that is most general is that of the distinction between wit and humor, albeit a thousand times expounded by impartial observers having neither. Now, it will be found that, as a rule, a shoemaker knows calfskin from sole-leather and a blacksmith can tell you wherein forging a clevis differs from shoeing a horse. He will tell you that it is his business to know such things, so he knows them. Equally and manifestly (99) it is a writer’s business to know the difference between one kind of writing and another kind, but to writers generally that advantage seems to be denied: they deny it to themselves.

I was once asked by a rather famous author why we laugh at wit. I replied: “We don’t–at least those of us who understand it do not.” Wit may make us smile, or make us wince, but laughter–that is the cheaper price that we pay for an inferior entertainment, namely, humor. There are persons who will laugh at anything at which they think they are expected to laugh. Having been taught that anything funny is witty, these benighted persons naturally think that anything witty is funny.

Who but a clown would laugh at the maxims of Rochefoucauld, which are as witty as anything written? Take, for example, this hackneyed epigram: “There is something in the misfortunes of our friends which we find not entirely displeasing”–I translate from memory. It is an indictment of the whole human race; not altogether true and therefore not altogether dull, with just enough of audacity to startle and just enough of paradox to charm, profoundly wise, as bleak as steel–(100)a piece of ideal wit, as admirable as a well cut grave or the headsman’s precision of stroke, and about as funny.

Take Rabelais’ saying that an empty stomach has no ears. How pitilessly it displays the primitive beast alurk in us all and moved to activity by our elemental disorders, such as the daily stress of hunger! Who could laugh at the horrible disclosure, yet who forbear to smile approval of the deftness with which the animal is unjungled?

In a matter of this kind it is easier to illustrate than to define. Humor (which is not inconsistent with pathos, so nearly allied are laughter and tears) is Charles Dickens; wit is Alexander Pope. Humor is Dogberry; wit is Mercutio. Humor is “Artemus Ward,” “John Pheonix,” “Josh Billings,” “Petroleum V. Nasby,” “Orpheus C. Kerr,” “Bill” Nye, “Mark Twain”–their name is legion; for wit we must brave the perils of the deep : it is “made in France” and hardly bears transportation. Nearly all Americans are humorous; if any are born witty, Heaven help them to emigrate! You shall not meet an American and talk with him two minutes but he will say something humorous; in ten (101) days he will say nothing witty; if he did, your own, O most witty of all possible readers, would be the only ear that would give it recognition. Humor is tolerant, tender; its ridicule caresses. Wit stabs, begs pardon,–and turns the weapon in the wound. Humor is a sweet wine, wit a dry; we know which is preferred by the connoisseur. They may be mixed, forming an acceptable blend. Even Dickens could on rare occasions blend them, as when he says of some solemn ass that his ears have reached a rumor.

My conviction is that while wit is a universal tongue (which few, however, can speak) humor is everywhere a patois not “understanded of the people” over the province border. The best part of it–its “essential spirit and uncarnate self,” is indigenous, and will not flourish in a foreign soil. The humor of one race is in some degree unintelligible to another race, and even in transit between two branches of the same race loses something of its flavor. To the American mind, for example, nothing can be more dreary and dejecting than an English comic paper; yet there is no reason to doubt that Punch and Judy and the rest of them have (102) done much to dispel the gloom of the Englisman’s brumous environment and make him realize his relationship to Man.

It may be urged that the great English humorists are as much read in this country as in their own; that Dickens, for example, has long “rule as his demesne” the country which had the unhappiness to kindle the fires of contempt in him and Rudyard Kipling; that “the excellent Mr. Twain” has a large following beyond the Atlantic. This is true enough, but I am convinced that while the American enjoys his Dickens with sincerity, the gladness of his should is a tempered emotion compared with that which riots in the immortal part of John Bull when that singular instrument feels the touch of the same master. That a jest of Mark Twain ever got itself all inside the four concerns of an English understanding is a proposition not lightly to be accepted without hearing counsel. (1903)