{He who enters into the viscera of the earth to see the metals, minerals, stones, and gems; who observes the plants, quadrupeds, and serpents on the surface of the earth; he who immerses himself in the sea in order to contemplate the fish and other marine things; who lifts himself into the skies to wonder at so many different kinds of apparitions and generations, the birds and so many flying insects; and then perceives in them the mechanisms and the harmony of each smallest particle so well adapted to the whole—how could he then, seeing everything so infused with Providence and Divinity, how could he not detest Atheism [. . .]? —Carlo Dati, “Delle lodi del commendatore Cassiano dal Pozzo,” Florence 1664}

‹26 October. Heard today in my chamber around 9:20 A.M., while reviewing the Champions League match between Milan and Bate Borisov, a singular, sharp cracking sound of the ball, which made me think of the snapping of an insect (with its wings or legs striking something). It was produced by Zlatan Ibrahimovic in his exuberant attempt to score a goal from an area in the middle of the pitch, which, as I gathered, in this part of the season is set to lay squarely in the sun like the glossy rubbing of a green vase on the window-sill.

I noticed a slight motion of the players at the apex of the Belarusan box, when suddenly, with a louder crack, the ball used in the match, which had been gnawed off by the nails of the boots, separated from Zlatan’s leg through a snapping sound on all sides of the sphere. It was a general and sudden bursting, just the type of contraction sought after by Massimiliano Allegri as his style of coaching—a dark world where a Milanese homo faber, lately embodied by the Ghanaian Boateng, brazes his meal to the buffeting of zonal marking winds, with more meat than smoke, and occasionally strikes thunder-like shots. The sound and motion of the whole midfield diamond adjusted as by a force pent up within. (I suppose the strain only needed to be relieved in one point for the whole to go off.) Ibrahimovic himself, after his silly miss, regained some composure from the awkward posture of his shooting, gave out a mustachioed grin while shaking his ninja pony-tail, and returned to engage the enemy’s defense from a far.

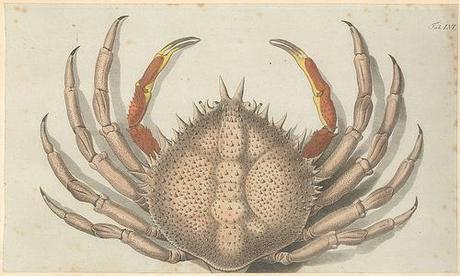

Never as in the last season have Zlatan’s moves resembled more clearly the muffled rustling of a crustacean—the peculiar crab walk of a powerful central striker who enjoys playing away fromdanger, neither drifting between the lines, with his oblique positioning, nor merely conforming himself to the theory of the ‘false nine’ role.

And again, in Milan’s recent cloak-and-dagger 4-3 against Lecce, I heard that sharp cracking, snapping sound. Hastening to the images, I found that another pine-like cone had gathered in midfield, laying in the sun or where the sun has reached, and then separated its scales very slightly at the apex of the offensive strategy. It was discoverable only on a close inspection; but while I looked, Ibrahimovic’s whole cone of operations culminated with a smart crackling, and rocked and seemed to bristle up, scattering the dry substance of his ballistic trickery on the surface of the pitch.

They all fairly loosen and open, the strikers in the Serie A, though they do not at once spread wide open. Milan’s dependance on shots from distance may be an adjustment to the old age of many players, or else it may reflect specific exercises in the training camp. It is almost like the disintegration of glass. A soon as the tension is relaxed in one part, is relaxed in every part.

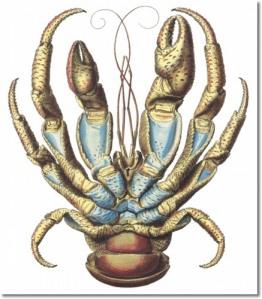

A Swedish international with obvious Slavic origins and erratic habitat, Zlatan Ibrahimovic has always been described by teammates and managers alike as shrewd and industrious, provident to the point of providential, good boatman and fighter braver than most of the civilized footballers in the Nordic lands of Europe. If he was ever a crab, Ibrahimovic would be a large, terrestrial one, such as the Birgus latro of the East Indies seen in this plate, which feeds on cocoanuts. Notoriously non-committal and known for its propensity to the hermit life, Birgus latro has the abdomen symmetrical and covered with a series of horny plates, befitting a samurai-like warrior or a long-serving officer, so that it requires no borrowed shell or other artificial protection. (Zlatan, after all, is not adverse to the assistance of various adjunct-striker figures but, unlike the dynamic duo, say, of Totti and Perrotta, is supporting them rather than the other way around.) This specimen, moreover, may reach a size larger than any other land crab, enabling it to handle the largest nuts. In his 1885 book, A Naturalist’s Wanderings in the Eastern Archipelago, published in New York, Forbes observes that, aside from modifying its gills as to function as lungs, one of the crab’s pincer-claws is developed into an organ of extraordinary power, capable, when the creature in enraged, of breaking a man’s arm. While I would not swear Ibrahimovic’s flesh is edible, I do believe that he could solely feed on drupaceous fruits, like cocoanuts or soccer balls. He would not climb into the palms of aerial fights to gather them, as it has been asserted by lesser coaches, but simply hammer them away as they periodically fall off the trees of football. What’s most, as a crab-striker, his walk would make sense.

A Swedish international with obvious Slavic origins and erratic habitat, Zlatan Ibrahimovic has always been described by teammates and managers alike as shrewd and industrious, provident to the point of providential, good boatman and fighter braver than most of the civilized footballers in the Nordic lands of Europe. If he was ever a crab, Ibrahimovic would be a large, terrestrial one, such as the Birgus latro of the East Indies seen in this plate, which feeds on cocoanuts. Notoriously non-committal and known for its propensity to the hermit life, Birgus latro has the abdomen symmetrical and covered with a series of horny plates, befitting a samurai-like warrior or a long-serving officer, so that it requires no borrowed shell or other artificial protection. (Zlatan, after all, is not adverse to the assistance of various adjunct-striker figures but, unlike the dynamic duo, say, of Totti and Perrotta, is supporting them rather than the other way around.) This specimen, moreover, may reach a size larger than any other land crab, enabling it to handle the largest nuts. In his 1885 book, A Naturalist’s Wanderings in the Eastern Archipelago, published in New York, Forbes observes that, aside from modifying its gills as to function as lungs, one of the crab’s pincer-claws is developed into an organ of extraordinary power, capable, when the creature in enraged, of breaking a man’s arm. While I would not swear Ibrahimovic’s flesh is edible, I do believe that he could solely feed on drupaceous fruits, like cocoanuts or soccer balls. He would not climb into the palms of aerial fights to gather them, as it has been asserted by lesser coaches, but simply hammer them away as they periodically fall off the trees of football. What’s most, as a crab-striker, his walk would make sense.

All of this backwardness up front—like a giant porcupine getting stuck in the underbrushes— is just a little too strenuous (or eccentric). With his tropical crab walk, Ibrahimovic seems to be trying too hard to clear his name from the taint of footballing heterodoxy. Zlatan is, perhaps, the last of the intellectual libertines: those who conducted experiments in the laboratories on behalf of Europe’s learned academies. Out of the great strikers of modern times, in fact, he stands like Galileo among the Linceans. And while Galileo’s contributions to the history of science have long been appreciated, the Linceans’ have not; by the time Galileo was defeated, they too were spent, or dead. Only with the rediscovery of the tactical drawings they made together can we finally begin to recover a full measure of achievement in the Linceans who accompanied the master. ♦

Previously in this series: Ecologies of Manchester City; subsequently in this series: Milan’s Pitch-Pine Cone Shapes.